The Color Explosion

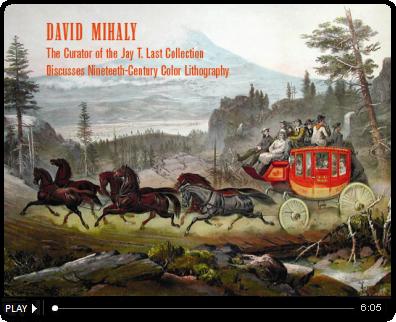

California & Oregon Stage Company advertising poster, lithographed by Britton & Rey (San Francisco), ca. 1870. Jay T. Last Collection, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Trade card for J. Ludington & Co.'s Baltimore Oysters, lithographed by The Calvert Lithographing Co. (Detroit), ca. 1890. Jay T. Last Collection, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Parlor foot-ball board game, created and lithographed by the McLoughlin Brothers (New York), 1891. Jay T. Last Collection, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Oct. 17, 2009–Feb. 23, 2010

Boone Gallery

In the 19th century, color lithography created a communication revolution and brought art, literature, and music to the masses. The process had a dramatic impact on consumer culture, too, as colorful and appealing product labels began to influence advertising, branding, and customer choices. Everything from cigar boxes to children’s games suddenly exploded with color. “In short, color lithography transformed American culture,” says David Mihaly, curator of lithographic history and ephemera at The Huntington.

Mihaly organized a new exhibition that highlighted one of the largest collections of color lithography in the United States. “The Color Explosion: Nineteenth-Century American Lithography from the Jay T. Last Collection” opened Oct. 17 and continued through Feb. 22, 2010, in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery.

The exhibition featured more than 250 objects, including advertising posters, art prints, calendars, children’s books, product labels, sales catalogs, sheet music, toys, and trade cards. An antique lithographic press was also on display.

The Jay T. Last collection—about 135,000 objects in all—had never before been on public view and is a gift in progress to The Huntington. For scholars, the material will serve as a significant resource in social history as well as the history of commercial advertising. “The collection opens a wide window onto the developing field of graphic arts in the 19th century as a means of expressing cultural ideas,” says David Zeidberg, Avery Director of the Library.

Last, a physicist and founder of Fairchild Semiconductor Corp., is also an independent scholar of the history of lithography. He is the author of the award-winning book The Color Explosion: Nineteenth-Century American Lithography (Hillcrest Press, 2005).

About Lithography

Lithography was invented in the late 1790s by Alois Senefelder, a young German playwright who sought a cheaper and faster way to publish his plays. Unlike copper engraving or woodblock printing, the newer printmaking process did not require any cutting into metal or wood. Instead, an image was drawn with a greasy crayon onto a flat block of limestone. The lithographer applied water to the stone and then a layer of ink. The ink adhered to the greasy surface, but nowhere else, as the lithographer then pressed paper against the stone to produce an image. Early lithographers used only black ink and recruited workers to hand-color illustrations for books.

“The printing technique was a great achievement,” says Mihaly, “but its full impact wasn’t felt until color entered the picture in the mid-19th century.”

In an education room adjacent to the gallery, children and families had an opportunity to explore the five major stages of lithographic production: stone preparation, drawing on stone, application of water and ink, printing, and cleaning the stone for the next job.

The Influence of Lithography

American print shops started applying multiple colors beginning in the 1840s, leading to the proliferation of printed color in book illustrations and sheet music. By the 1870s, salesmen were pitching products using graphic trade cards and catalogs, and homeowners were decorating their walls with color prints, posters, and calendars.

The exhibition showed the veritable explosion of color that filtered to consumers in mid-19th century America. Among the items on view were a sampling of lithography that found its way to the shelves of general stores on food cans, fruit crates, and other merchandise. The invention of lithography has a direct link to the early history of branding and advertising, as manufacturers and merchants began to recognize the powerful appeal of a package over the actual product. Generic goods in barrels, jars, bins, and sacks were replaced by brand name products in eye-catching boxes, cans, cartons, and wrappers. Color lithographed labels provided crucial identification and promotion in a sea of consumer choices.

Lithography not only changed the way consumers interpreted the world but also the way merchants constructed the space for selling products. On cigar boxes, for example, large labels were pasted inside lids that were then opened and displayed in tobacco shops. Cigar box labels remained a staple of lithographic production until the early 1900s when cigarettes overtook cigars in popularity and the need for labels shrank with the package size.

Color lithography dramatically altered a publishing world that previously had been constricted by the limits of hand coloring. Natural history books of mammals, birds, fish, flowers, and fruit abounded. Scientific treatises, medical reports, government land surveys, and architectural texts often made special use of color to convey complex information.

Lithographers also applied their skills to the depiction of current events. As advances in printing accelerated production and lowered costs, lithographed prints became popular news sources and helped launch the field of pictorial journalism. In one of the earlier examples of this trend, New York lithographer Henry Robinson produced Battle of Buena Vista shortly after that 1847 Mexican-American War confrontation.

The ubiquity of examples from the Last collection extends to toys and games. The well-known game pioneer Milton Bradley was, at first, a lithographer. In the early 1860s, he created and printed a simple lithographed board game called “The Checkered Game of Life.” By the 1870s Bradley had become one of America’s biggest game manufacturers and helped launch the American game industry.

Curator Highlights

Curator David Mihaly highlights several works from “The Color Explosion.

PLAY

This exhibition was made possible through a bequest from Elizabeth Kite Weissgerber.

Additional support was provided by Robert F. and Lois Erburu, J.W. and Ida M. Jameson Foundation, Estate of Mr. Allan Q. and Mrs. Margaret Mowrey Moore, The Ahmanson Foundation, the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, and the Melvin R. Seiden-Janine Luke Exhibition Fund in Honor of Lois and Robert Erburu.