Illuminated Palaces: Extra-Illustrated Books from the Huntington Library

Irving Browne, Iconoclasm and Whitewash. New York, 1886. Illustrated by the author. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Anthony, Count Hamilton, Mémoires du comte de Grammont. London, 1794. Illustrated by Richard Bull. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

July 27, 2013–Nov. 19, 2013

Library, West Hall

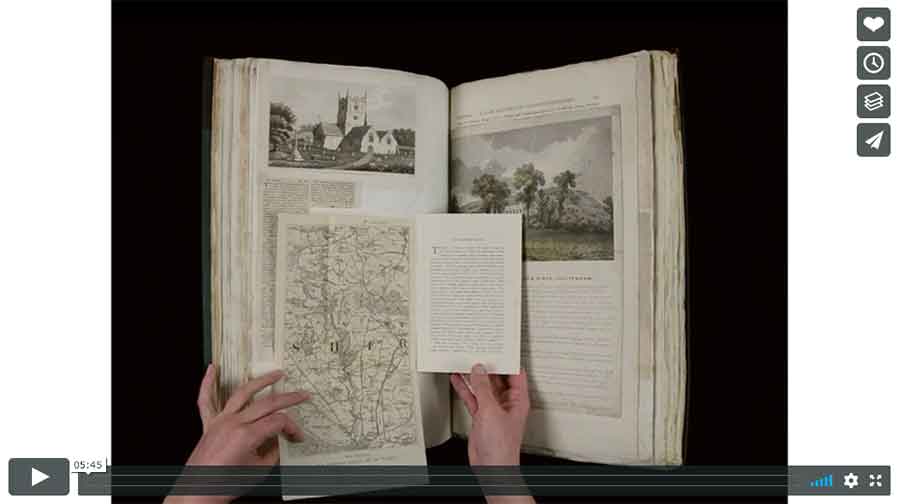

In the 18th and 19th centuries, historians, bibliophiles, and collectors turned ordinary books into extraordinary “illuminated palaces”—repositories for original art, prints and engravings, maps, autograph letters, and the excised pages of other, more famous books. This process of destruction and transformation, often called “extra-illustration” or “grangerizing” (after its most famous early advocate, the Rev. James Granger, an 18th-century cleric), was once a genteel hobby in the United States and Britain.

"Illuminated Palaces: Extra-Illustrated Books from the Huntington Library,” features approximately 40 works dating from the late 1700s to the early 1900s, when the practice was most popular.

“It’s at once fascinating and horrifying—the idea that someone would purposefully destroy a book in order to build their own custom creation,” said Stephen Tabor, curator of early printed books at The Huntington and co-curator of the exhibition with Lori Anne Ferrell, professor of English and history at Claremont Graduate University.

Perhaps the most impressive example in The Huntington’s collection is the Kitto Bible: 60 massive volumes with more than 30,000 prints, engravings, drawings, and other inserted materials. One huge volume of the Kitto, containing just the books of Romans and 1 Corinthians, will be included in “Illuminated Palaces.” Shakespeare’s work also appealed to Grangerizers, and the exhibition features an extra-illustrated set of his works with the original nine volumes expanded to 45. The hobby of Grangerizing fell out of fashion in the early 20th century, and few bibliophiles were sorry to see it go. “For today’s book lovers and book conservators, it’s considered a very questionable practice,” said Ferrell. But she and Tabor would be the first to admit that it also represents a fascinating chapter in the history of the book.