Chronicles of Childbearing

Posted on Tue., Nov. 15, 2016 by

The Longo Collection traces seismic shifts in obstetrics and gynecology over six centuries

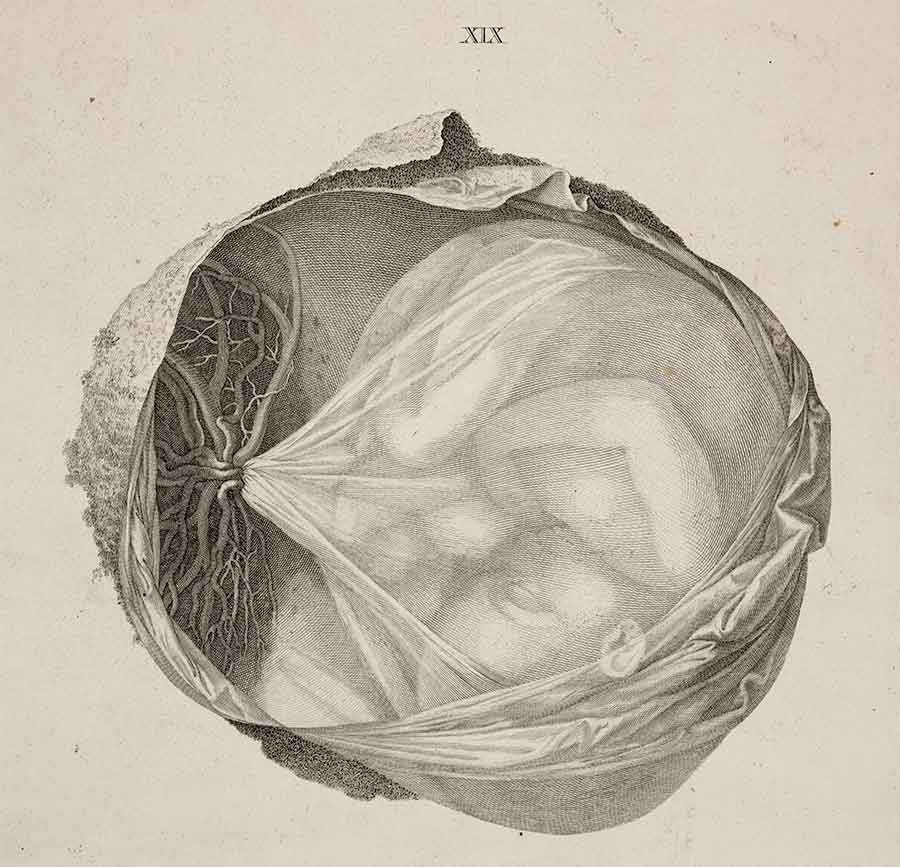

Illustration of a fetus in the womb from Samuel Thomas von Soemmerring’s Icones embryonum humanorum, 1799.

The images are haunting glimpses into the most primal and private of human moments—the experience of birth. There is a woman assisted by two midwives, demure and fully clothed, in labor behind drapes of linen that shroud her body, her baby, and the four-legged birthing stool commonly used in Europe in the 16th century.

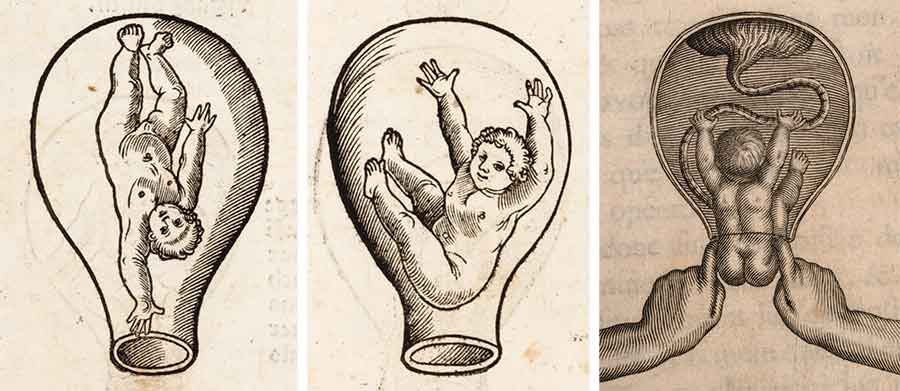

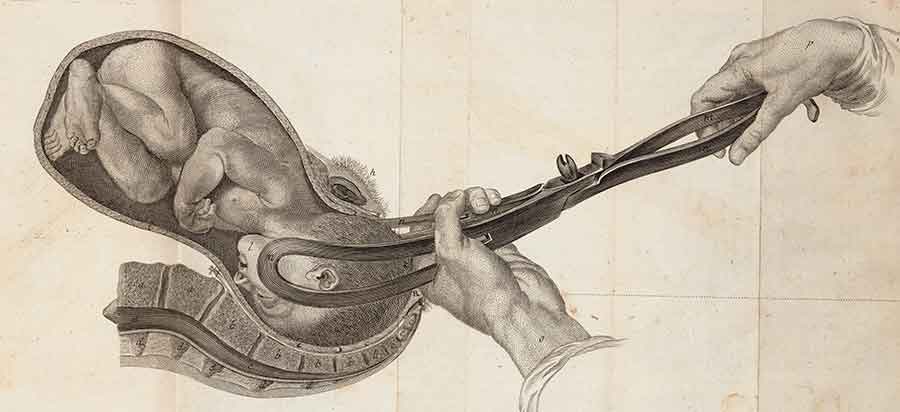

A 17th-century print shows a uterus shaped like a giant light bulb, with a far-too-small baby being teased out by two index fingers. A depiction from a century later is much more realistically drawn, showing the baby grasped by long forceps. An 18th-century color plate is deeply unsettling: a pinkish-red baby wedged, perhaps trapped, atop the pelvic girdle with one tiny arm dangling out. The images—among the earliest depictions of female reproductive organs in print—emerge from an extraordinary collection of thousands of rare books and reference materials on women’s health and reproduction collected single-handedly by Lawrence D. Longo, an esteemed local researcher and physician, over the past six decades.

Bequeathed to The Huntington before Longo’s death this year, the materials now known as the Lawrence D. and Betty Jeanne Longo Collection in Reproductive Biology vastly augment the Library’s growing holdings in the history of science and medicine. They also provide an unusually deep look at a provocative topic of scholarly, popular, and political interest—the female body.

“Rather than having to find material about women buried in other collections, this entire collection focuses on women and their bodies,” says Melissa Lo, Dibner Assistant Curator of Science and Technology at The Huntington. “The Longo collection is a very deep dive into one subject area. It’s really a treasure trove for the category of obstetrics and gynecology.”

The collection spans six centuries, from the early 15th to the 20th, and includes some 2,700 rare books along with 3,000 pamphlets, journal articles, and reference works in Latin, French, English, German, Italian, and Dutch. The collection also contains 350 incunabula—books from the 15th century that were printed using metal type. One of these, a 1494 text titled De secretis mulierum et virorum (“The Secrets of Women and Men”) by Albertus Magnus, is bound to another incunabulum that had been printed earlier.

Longo, a Los Angeles native who died in January at the age of 89, had a long and venerated career. He was a World War II veteran, a missionary to Africa, and a historian, but he was best known for his pioneering research at Loma Linda University School of Medicine, where he attended medical school and eventually became the Bernard D. Briggs Distinguished Professor of Physiology and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Illustration of a woman giving birth, assisted by two midwives, from Eucharius Rösslin’s Der swangern Frauwen und hebammen Rosegarten, 1513.

Longo founded the university’s internationally known Center for Perinatal Biology, leading a research program that sought to understand how complex diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, have origins in fetal development. He holds the distinction of being one of the longest-funded researchers at the National Institutes of Health. Throughout his career, he helped lead the charge to put warning labels on cigarettes, wrote more than 350 scientific papers, edited the “Classical Contributions” column of the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and wrote or edited more than 20 books. He was also known for his sense of humor: his final book, a collection of illustrations of the gravid uterus published this year, is titled Wombs with a View.

While Longo was a gifted researcher and prolific writer, one of his greatest passions was collecting books. He described himself as a bookman and his bibliophilia as an illness from which he had “no desire to be cured,” and he called his collection “a complex tapestry” into which he was continually weaving new items.

Longo’s love of collecting books began in medical school, inspired by an essay written by Sir William Osler, the esteemed Canadian physician who co-founded Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore in 1889. During his lifetime, Osler collected 8,000 medical books, which are now housed at his alma mater, McGill University. The essay prompted Longo to make repeated trips to the “red barn,” a replica Pennsylvania Dutch barn on La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles that once housed the wares of the legendary Los Angeles rare book seller and medical book enthusiast Jake Zeitlin.

Hunting for books was sometimes lonely work, even for the reserved Longo. “Most people do not want to hear about a bibliophile’s latest great find,” he once said, “even if it is a vellum incunabulum.”

Veteran rare book dealers say it is remarkable for a single individual to amass such a large and valuable collection; Longo is praised for his good taste and keen eye. The books were once piled so high in Longo’s office that staff at Loma Linda University—which sits astride the San Andreas Fault—say they feared a quake might bury the researcher under his beloved tomes. Now at The Huntington, the collection fills about 230 linear feet of shelf space.

Left and center: Illustrations of fetuses in utero from Eucharius Rösslin’s Der swangern Frauwen und hebammen Rosegarten, 1513. Right: Illustration of a baby being teased out by two index fingers from Cosme Viardel’s Observations sur la pratique des accouchemens naturels, contre nature, & monstrueux, 1671.

“I think it’s absolutely wonderful that the collection is at The Huntington,” says Dr. Garth Huston, Jr., an anesthesiologist from San Diego and the son of Dr. Garth Huston, Sr., a close friend of Longo’s and an esteemed collector who specialized in books about 17th-century English medicine. “He and my dad would often have long discussions about what to do with their collections.”

Huston recalls the collections of both men as open, working libraries despite their immense monetary value. “You could just pick up a book and look through it,” he says. Many collectors of history of medicine books work with dealers to focus on a specific area as Longo did. The elder Huston died in 1989, but his son is now collecting books on the history of asthma, resuscitation, drowning, and swimming instruction.

Lo joined the Huntington Library staff two years ago after earning her Ph.D. in the History of Science at Harvard University. The Longo collection will be the first for which she’s been designated lead curator. She’s spent the past few months just trying to get a grasp of the depth, richness, and specificity of the new holdings. And she is still amazed by what she is finding: odd advice from Victorian physicians urging girls not to play the piano for fear it will stunt their growth, gruesome case studies of 92-pound tumors, depictions of Siamese twins, and home recipes for abortions from the 1600s.

She is mesmerized by images in André Levret’s 1753 L’art des accouchemens (“The Art of Delivery”) that depict the uterus changing perfectly symmetrically and proportionally throughout pregnancy; Levret constructed the drawings using pure math rather than empirical evidence. And she’s noticed a steady stream of patronizing 19th-century advice on marriage and hygiene. “There’s a lot of suggesting that a woman’s mind is different from a man’s mind,” Lo says.

During a visit to The Huntington’s library stacks, Lo carefully opens a vellum-covered book tied with a thin leather strap. It’s an extremely rare first edition of the first-known printed manual for midwives, Der swangern Frauwen und hebammen Rosegarten (“The Rose Garden for Pregnant Women and Midwives”), published in Germany in 1513 by Eucharius Rösslin. Though written by a man, the information was gleaned from female midwives, she says, as men were largely prohibited from delivering babies in that era.

Illustration of a baby being delivered with forceps from Jean-Louis Baudelocque’s L’art des accouchemens, 1781.

The vellum cover, Lo points out, was an unrelated 16th-century German document used as a binding. “This is an example of how many different parts of a book you can investigate and how—especially in the case of books published between the late 15th and late 18th centuries-—one book is not like any other,” Lo says.

Many scholars today work from digital copies of rare books and manuscripts that they can often download directly onto their computers. While convenient, these digital copies often leave out such details as marginal notes, related papers, and receipts tucked into books that can hold valuable auxiliary information. Some centuries-old books on midwifery, for example, are inscribed with records of attended births. And many of the items in the Longo Collection, including rare pamphlets printed for midwifery education in provincial settings within Europe, have never been digitized.

“Any particular book is a unique object,” says Mary Terrall, a professor of history at UCLA, who has co-edited a volume on 18th-century views of conception, life, and death and who plans to use the new collection for future research. “There’s something about working with the same physical object that people have worked with down through the centuries.”

Taken as a whole, the collection documents seismic shifts in the knowledge of women’s health and the ways in which women were depicted and treated. One example is the changing role of who assisted women in childbirth. Traditionally, midwives attended most births, helped by female relatives and neighbors. Surgeons were called only in emergency situations, Terrall says.

The long history of the gradual medicalization of childbirth, in which the normal process of birth became routinely characterized as a potential emergency, can be told through books written by surgeons, midwives, and physicians, she adds. Some of these books were used as textbooks; some were written to promote rival techniques and technologies. One current question is why women allowed this medicalization of birth to happen. This is an active area for scholars, and one that has many of them eager to mine the Longo Collection for their studies.

“Childbirth is both mundane—everyone is born, after all—and momentous. The knowledge, beliefs, and practices associated with this ubiquitous event differ radically in different times and places,” says Terrall, who teaches a class at UCLA called “Midwives, Mothers, and Medicine.” “The history of childbirth in European and American cultures is a long and complicated one, filled with disputes as well as discoveries. Because debates about how best to deliver babies often took place in print, a collection like this is particularly useful for tracing these developments.”

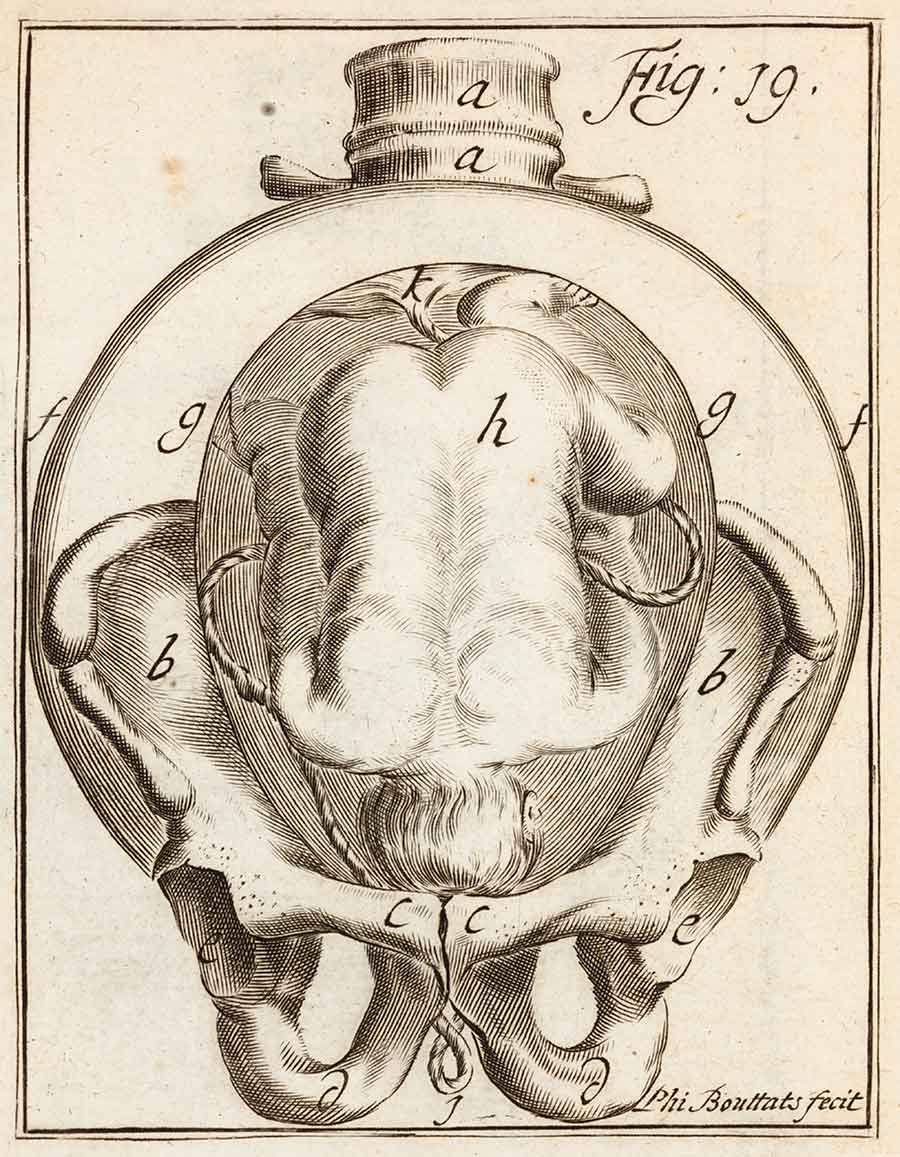

Illustration of a fetus in the womb in Hendrik van Deventer’s Operationes chirurgicae novum lumen exhibentes obstetricantibus, 1701.

Carla Bittel is an associate professor of history at Loyola Marymount University who studies the history of gender, medicine, technology, and science in the 19th century and has written a book about New York physician and activist Mary Putnam Jacobi. Several years ago, she had the opportunity to visit Longo and see the collection while it was still on the shelves in his study.

“He was a physician and medical researcher who also truly valued history. He surrounded himself with it,” she says. “You don’t normally see a 16th-century volume on a shelf in someone’s house.”

She’s since had a chance to briefly examine the holdings at The Huntington in order to advise Lo. The collection is so powerful for scholars that moving through it can be a palpable experience. “As you walk through the collection, a story unfolds about the perception of women’s health and women’s bodies,” she says. “As a whole, the books become a visual representation of changing ideas.”

The collection is dominated by male authors, a fact that mirrors the history of medicine itself. “You get a sense for how medicine defined women’s bodies and women’s roles, especially reproductive roles,” Bittel says. “At the same time, you can see in the books that debates were happening. You get a sense that the female body was often contested territory.”

While the rarest and oldest books are one strength of the collection, Bittel says she is also interested in some of the more popular health volumes that Longo collected, including books for the layperson on trends such as phrenology and water cures, as well as advice books with titles such as What a Young Girl Ought to Know (1897). While such titles sound patronizing to today’s ears, Bittel says this literature drew the interest of women who were eager for health information.

The Huntington has long been known for its substantial collection of European books dating back to the 11th century and its extensive archive of materials about the American West, but it is now increasingly recognized for its holdings in the history of science and medicine, says Daniel Lewis, Dibner Senior Curator of the History of Science and Technology.

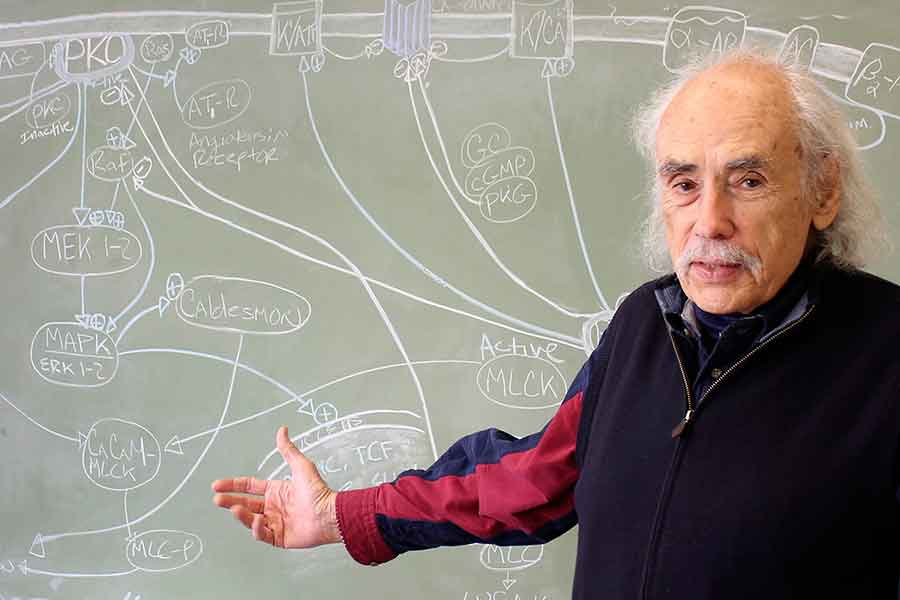

Lawrence D. Longo (1926–2016), standing before a diagram of the main signaling pathways that govern vascular contractility, which is how forcefully arteries constrict and relax. Photograph by James Ponder, Loma Linda University Health.

“Our history of science collection, broadly speaking, is one of the best in the world. But our history of medicine collection is a little bit more idiosyncratic and loosely gathered,” Lewis says. “The Longo Collection changes that. It’s very focused, so you get both breadth and depth. And it’s on a topic that’s so fundamentally important to the study of medicine—the arrival of new life.”

The early library collection did contain some books on science and medicine, primarily because Henry Huntington often purchased large collections that included them, Lewis says. The science collection started to grow in a systematic way in the 1970s when former Library director Daniel Woodward realized the holdings in science were what he called “irregular” and sought to collect more. Soon afterward, the library obtained the papers of astronomer Edwin P. Hubble, as well as the library of the Mt. Wilson Observatory, where Hubble conducted his experiments.

Lewis credits curator Alan Jutzi, who worked at the Huntington for 45 years before retiring this year, with helping to bring a wealth of science and medical material to The Huntington—including a 6,700-item archive from the Los Angeles County Medical Association, a substantial group of Darwin materials, and the Longo Collection. The Library’s holdings in science and technology increased markedly when the 67,000-volume Burndy Library, collected by engineer and industrialist Bern Dibner, moved to The Huntington from its former home at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2006.

Lo and other library staff currently are working to organize and catalog the Longo Collection and its associated ephemera so that they can be made available to scholars as quickly as possible. Lo’s already fielding requests to study the works.

With debates looming about women’s reproductive rights and transgender issues, the collection has arrived at The Huntington at an especially fruitful time, says Lo. “I am so thrilled. It gives us an opportunity to think about gender in myriad ways, to give people the means to ask some of the most central questions in the history of medicine,” she says. “What does it mean to come into this world? What does it mean to be female? What does it mean to be human?”

Usha Lee McFarling is a Pulitzer Prize–winning freelance writer based in South Pasadena, Calif.