Lessons Learned: In the Woods With a Canoe

Posted on Sun., Oct. 1, 2017 by

A historian of camping scrutinizes Frederick Jackson Turner’s encounter with wilderness

Camping is one of the country’s most popular pastimes—tens of millions of Americans go camping every year. In Heading Out: A History of American Camping, Terence Young, professor emeritus of geography at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, takes readers into nature to explore with them the history of camping in the United States.

Young shows how camping progressed from an impulse among city dwellers to seek temporary retreat from the stress of urban living to a form of recreation so popular that it spawned an entire industry. And he points out the not-so-bright side of camping’s history, when segregated campgrounds at the national parks underscored the nation’s fraught race relations. Young also focuses on key figures in its development, showcasing a sampling of campers and their excursions.

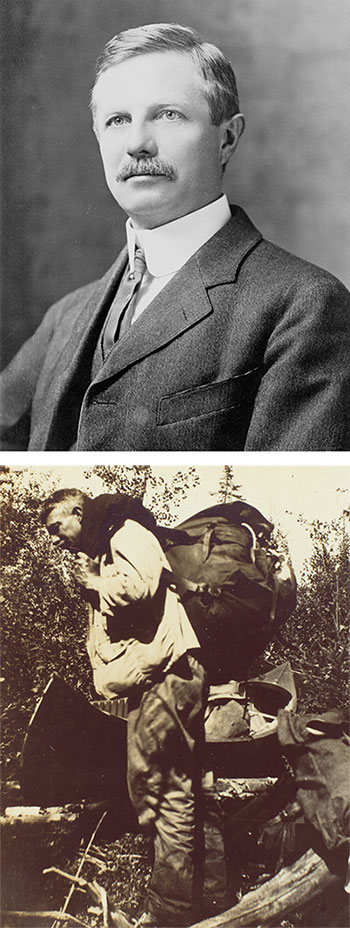

Among those featured is Frederick Jackson Turner (1861–1932), perhaps the most influential U.S. historian of the first half of the 20th century. Best known for his “Frontier Thesis,” which he set forth in a scholarly paper published in 1893, Turner attributed the development of a distinctly American character to the nation’s westward expansion. After a long and distinguished career as a history professor, Turner joined The Huntington as a research associate in 1927. The Huntington acquired his papers after his death in 1932.

Although many researchers have studied Turner’s archive for its scholarly content, Young is the first to study Turner’s musings on camping. The following is an excerpt from Young’s book that focuses on a month-long canoe-camping trip that Turner, his family, and the family of the president of the University of Wisconsin took together in the summer of 1908. Race would become a factor here, too.

The label for this image in one of the Turners’ photograph albums of their 1908 canoe trip reads: “Kahnipiminanikok / Dow and the Turners en route.” “Kahnipiminanikok” is the Ojibwe name of Kawnipi Lake in Ontario, Canada. Seated in the bow seat is historian Frederick Jackson Turner (far right); behind him sits his wife, Caroline Mae Turner (second from right) and their daughter, Dorothy K. Turner (third from right). Jesse Dow (far left), one of the trip guides, sits in the stern seat, steering the canoe. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Among these [boat-camping] enthusiasts was no less a figure than Frederick Jackson Turner. Although the historian had expressed a concern for the “closing” of the American frontier, pockets of wild nature nonetheless remained, and he frequently canoe camped through them as an escape from his everyday life. Turner’s taste for camping and fishing began during his youth in Portage, Wisconsin, a small town near the frontier when he was born in 1861. Turner’s father, Andrew Jackson Turner, loved the out-of-doors, especially fishing and hunting. The younger Turner, who considered himself and his father to be “comrades,” similarly embraced outdoor activities wholeheartedly, especially fishing. As he grew into a college student and then a professor (at the University of Wisconsin at Madison from 1890 to 1910 and at Harvard University from 1910 to 1922), Turner frequently spent his summers fishing and camping. One biographer noted that Turner often began fall semester “trim and tanned” because of these summer outdoor vacations. Many of these vacations, such as the one he enjoyed during summer 1908, relied on canoes. On Aug. 10 of that year, Turner, his wife (Caroline) Mae, and their daughter Dorothy departed on a canoe-camping trip through southern Ontario Province with Charles Van Hise, a geologist and president of the University of Wisconsin, and his two daughters Mary Janet and Hilda. Paddling and portaging from Basswood Lake on the Minnesota-Ontario border to Lake Nipigon north of Thunder Bay, they covered nearly four hundred miles.

Top: Portrait of Frederick Jackson Turner (1861–1932), ca. 1905. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Bottom: Frederick Jackson Turner “on the portage,” according to the label for this image in one of the Turners’ photograph albums of their 1908 canoe trip. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Both Turner and his wife left accounts of their vacation—a later letter by him to fellow historian and friend Max Farrand, [who became the first director of research at The Huntington in 1927], and a personal journal by her—which occasionally reveal how their wilderness travels were a pilgrimage into sacred space. According to Turner, the campers “had a bully taste of the real wilderness” on this canoe-camping adventure. They slept in beds only once, cut their own trails at times, saw no one new for three weeks, encountered moose and bear, and caught and ate so many fish that “we filed the barbs off our hooks to keep from getting too many to eat.” The six campers were assisted by four men that Van Hise had “borrowed from the force of the Oliver mining company which let us pay them and use them in a dull season.” In Turner’s view, these men were “real bullies of the northern woods” whose experiences had made them into rugged, pioneer-like individuals. “Erick the head guide was a canny Swede who has lived in the woods some thirty years and can do anything.… Dow was a Canadian Scotch man—a true sport…. McCabe was a fine Irish man, strong as the propeller of an ocean liner at the stern paddle, and then there was the cook [Fred Landry], a French Canadian, with the gasconade of his people, but clever with the frying pan.” These four men supported the camping party for the entire time by being the principal paddlers in three of the four canoes, by portaging most of the approximately one thousand pounds of supplies and gear, by almost daily erecting and striking their encampments, and by preparing all meals. Although the campers were generally “roughing it,” they had time to relax and ate well.

One dinner, Mae Turner recounted, was an especially elaborate delight, since they had been camping for more than three weeks at the time. Dinner, she noted in her journal for Sept. 2, was “pea soup—very good. Trout and bacon—sweet potatoes…hot baking powder biscuit—blueberry pie—blueberries—cheese—coffee.” This sumptuous meal was followed the next morning by a similarly impressive repast: “blueberries, prunes, Oatmeal, trout, bacon, toast & coffee—and some left over blueberry pie.” However rough other elements may have been, the cook made their meals quite smooth.

As the 10 traveled their route, they sometimes admired the landscape, just as other, romantically inclined campers had before them. A few days into their trip, for instance, Van Hise termed the scene at one lake a “Hogarthean line of beauty from mountain to valley,” which prompted Turner to remark, “My I love these trees. Look at those leafy isles.” On another occasion, a landscape feature recalled the fading frontier for Turner. “We had a little taste of the old Dawson Route from Fort William to the Rainy river,” he happily reported to his historian friend Farrand. The Dawson route had been a wide trail that ran from Thunder Bay to the Red River district of southern Manitoba. Initially surveyed by S. J. Dawson in 1858 and opened about 1870, it was slowly being reclaimed by the forest and largely unused, except for local traffic, when the Turners and Van Hises encountered it in 1908. “The old portages cut out for teams and with corduroy road in places,” observed Turner, “made a contrast with the Indian portages we had been following.” The former were more open and easier to travel, but “not altogether to our taste.” The Dawson route, it seemed to Turner, was out of place and an invasion of sacred wilderness because “it looked like civilization.”

Ethnicity and race also challenged Turner, his companions, and their guides as they canoed across southern Ontario. Parts of this wilderness were home to Canada’s First Peoples, but evidence of their presence distressed Mae Turner. On one occasion, she recorded in her journal, the company established camp “on a point commanding all the area,” but she wished it was elsewhere. “Attractive” pine groves on other points caught her eye, but more importantly, nearby their campsite sat “the frame of an Indian tepe.” Where the Dawson route had inspired Mae’s husband to recall frontier history, the native structure gave her “the feeling that the place is unclean,” even though it had not been occupied for years. “Camping on virgin ground,” she concluded, “spoils one.”

A few days later, as the campers prepared to head their canoes up the Nipigon River, they faced a dilemma that again involved First Peoples. The superintendent of the river and the local populace “protested against our party going up with light canoes and no Indians,” recounted Turner. Van Hise and the hired men dismissed these protestations, telling Turner that they could do it on their own. Turner, however, disagreed with the other men, insisting that his family had to have a “Nipigon canoe” (a twenty-foot, dory-like boat) and an Indian guide who knew the river and where to fish. Turner’s stance, he lamented, “greatly disgusted Van Hise who hates Indians,” but Turner held firm nonetheless. Then, to his surprise, “Dow [the guide] kicked and would not paddle [in the same canoe] with an Indian.” Turner, finally revealing his own feelings, admitted that he “sympathized with [Dow]. He was a true sport; but I had made up my mind.” Subsequently, the party obtained its Nipigon canoe, and Dow, who had been at the stern of Frederick Turner’s canoe, exchanged with “amiable Mike” McCabe, who had been paddling in a canoe with the cook. The campers then departed upriver toward the next camp, where an outfitter had promised they would meet their expert aboriginal guide. Ironically, when the new man appeared the next day, “he proved to be a clever young bluffer, a white lad” with little experience, it later turned out. Perhaps Van Hise’s disgust, Dow’s “kicking,” and Turner’s sympathy had reached the ears of the locals, but for whatever reason, Turner admitted, “No Indian could be gotten to work with whites.” Consequently, the campers missed some good fishing “by not having an expert Indian who could take us into one or two places where prior knowledge was requisite.” Nevertheless, after the canoe campers completed their vacation on Sept. 10, Turner judged his travels a success because, like all true pilgrims, he had returned in a transformed state. “I am 20 pounds lighter & much more muscular,” he crowed. Only 46 at the time, Turner would continue to camp and fish for many years to come.

Left: The label for this image in one of the Turners’ photograph albums of their 1908 canoe trip reads: “The Sleeping Beauty FJT.” Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Center: Caroline Mae Turner found time to relax and read on her canoe-camping trip on the Nipigon River in the summer of 1908. Here she sits in camp at Pine Portage. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Heading Out: A History of American Camping by Terence Young, Cornell University Press, 2017.

The fact that the Turner and Van Hise families’ canoe-camping vacation had covered nearly four hundred miles was noteworthy, but its duration—one month—was unexceptional. Many, if not most, camping trips taken during this era tended to stretch to 30 or more days, making duration a factor that restricted camping’s appeal to a relatively small group of adherents. Few Americans possessed sufficient leisure time to vacation in any form. For most people, if they had the time to camp, it came as a result of the sort of ill health that would confine them to the house or because they were unemployed and without the money. Only as the 19th became the 20th century did paid vacations begin to be won by working people.

Terence Young is professor emeritus of geography at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.