Scholar's Insight: A Riveting Hypothesis

Posted on Sun., Oct. 1, 2017 by

The recess in a book’s cover may have contained more than meets the eye

Senior book conservator Andrea Knowlton (left) and Racha Kirakosian, assistant professor of German and the Study of Religion at Harvard University, look at a pear-shaped recess inside the front cover of a 15th-century Dutch codex known as Huntington Manuscript 1048. Photograph by Kate Lain.

One of the most pleasurable experiences one can have as a medievalist is coming across an artifact that triggers a chain of discoveries and unexpected connections. That happened to me when I was researching a codex from The Huntington’s collections, a 15th-century Dutch manuscript of devotional texts known as Huntington Manuscript 1048, or simply HM 1048. Produced in the northeastern part of the Netherlands around 1439, it contains meditations, sermons, and prayers from several authors.

In my work on medieval mysticism and materiality, I study manuscripts and the texts they contain in order to connect two things in seeming opposition: devotional culture dealing with transcendence and the physical nature of book production.

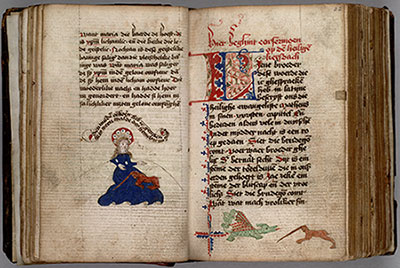

Left: Colored drawing of a virgin with a unicorn in her lap; on the facing page, the beginning of a sermon and, at the bottom of the page, a dragon and unicorn fighting. HM 1048, back/front of leaf 21 and 22. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Left: Colored drawing of a virgin with a unicorn in her lap; on the facing page, the beginning of a sermon and, at the bottom of the page, a dragon and unicorn fighting. HM 1048, back/front of leaf 21 and 22. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

I’m used to poring over book bindings, illuminations and miniatures, and “bookish” things. But HM 1048 stood out with a particular feature: a pear-shaped recess on the inside of the front wooden cover. This posed a conundrum. What was its use? Why was it there? Did it hold a devotional object, which would have been in keeping with the book’s religious and mystical contents? This would be palpable evidence for the link between devotion and corporeality, between mysticism and materiality.

The catalog entry suggested that an ampule of holy water could have been kept in the front cover’s recess, elevating the status of the book to that of a reliquary. Yet, the recess’s dimensions—approximately 2.6 inches long, nearly 1.4 inches at its widest, and 0.2 to slightly over 0.3 inches deep—would have hardly accommodated a glass container. Besides, such a precious book would not be the ideal place to keep liquids.

Upon further deliberation and consultation with colleagues, an intriguing hypothesis took shape: what if the reader of the Dutch manuscript needed eyeglasses that she kept in the book itself? Indeed, one particular type of medieval spectacles had a central hinge to sit on the nose, so-called rivet spectacles. Their lenses would be relatively thin (0.08–0.12 inches!), and if folded in a case, it would be pear shaped. A small pair of rivet spectacles would fit perfectly into the recess in HM 1048’s front cover.

There exists at least one other manuscript of the time with a front book cover carved out to contain spectacles (the manuscript with the shelfmark “Ms. L. 64,” located in the Bibliothèque Cantonale et Universitaire in Fribourg, Switzerland). The Huntington’s copy, however, seems unique. In contrast to the Fribourg book, in which the spectacles were kept with their lenses spread apart, HM 1048 would have accommodated a folded pair of rivet spectacles.

One can easily imagine that glasses were needed to read the pocket-size book, considering that the sometimes small handwriting was so difficult to decipher, especially in half-light. But who then owned the book and the suspected glasses?

Left: The rivet spectacles in this image would fold into a pear shape. Detail of The Presentation in the Temple by Friedrich Herlin (1425/30–1500), left inner panel of the high altar of the St. Georg church in Nördlingen, Germany, currently housed at the Stadtmuseum Nördlingen. Photograph: Institute for Material Culture–University of Salzburg. Right: Close-up of the pear-shaped recess inside the front cover of HM 1048. Photograph by Kate Lain.

An ex libris note on the book’s last page, dating from the time when most of the texts in the manuscript were copied, specifies in Dutch: dijt boek hort tuu inden meygaerd ende voert dije gemeijn susteren (“this book belongs to the May Orchard and was given to all sisters”). This indication of ownership is signed by Mechtel Pijls. A woman named Mechtelt Pijls is mentioned in the Utrecht archives in 1470, but we see no signs of a community named Meygaerd. Still, this would be a common nomenclature for a beguinage—a quasi-monastic but lay community of pious people.

Other details affiliate HM 1048 with a female monastic context, such as the depiction of a woman with a unicorn. According to medieval tradition, only a female virgin was able to catch the fantastic beast. The portrayal of the unicorn in the virgin’s lap preceding a sermon on the mystical bride speaks for a nunnery or some sort of female community as the place where the volume was produced and used. The fact that only brothers are addressed in the sermon is not a mistake on the scribe’s part, as the sermon harks back to textual and even oral traditions; it might originally have addressed a male community before it was circulated and copied.

Although we cannot be absolutely certain about when and where the codex was bound, the back flyleaf, attached to the back cover, is made from parchment recycled from a Latin breviary (book containing liturgical text) for nuns.

Returning to the point of departure: does the mundane use of the book’s cover as a container for spectacles diminish its links between devotional and material culture?

My short answer is, no, it does not. This codex is a wonderful example of a book put to personal and practical use while also serving as a medium of devotion within a community.

Racha Kirakosian is assistant professor of German and the Study of Religion at Harvard University, and was a short-term fellow at The Huntington in 2017.