A Passion for Cycads

Posted on Sat., April 1, 2017 by

Survivors from the dinosaur age, cycads continue to captivate collectors and researchers

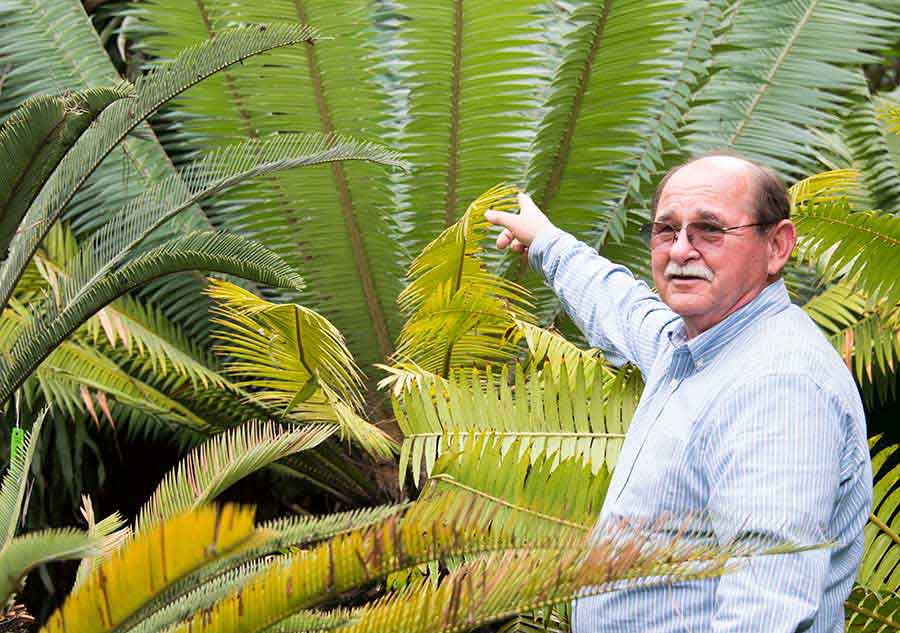

Brian Dorsey, research botanist, kneels before a Dioon merolae that came to The Huntington from the collection of Loran Whitelock (1930–2014), author of The Cycads, the standard guide to the plants. Photograph by Kate Lain.

Cycads are squat, woody, and branchless. They have no flowers, just spiky leaves that shred clothes and tear skin. They grow slowly, poison livestock and sometimes people. Despite these liabilities, the strange and primordial plants inspire a fierce, and sometimes inexplicable, ardor in their fans.

Once besotted, many collectors can’t stop themselves from amassing the rare, often expensive plants, many of which are severely endangered and illegal to transport across borders. “I’ve seen wealthy people show them off to people in walled gardens the way people used to show off Van Goghs and Chagalls,” says Tim Gregory, a cycad enthusiast and University of California Botanic Garden advisory board member who has spent the past three decades studying and propagating the plants. “It’s very weird.”

The obsession can disrupt lives: some collectors become cycad nurserymen. Others travel cross-country to scoop up a single plant. The late opera singer Ganna Walska, founder of Montecito’s Lotusland botanical garden, sold off nearly a million dollars’ worth of jewels to buy cycads. Many collectors jokingly refer to their addiction as “the green needle.”

What’s the draw? For some, the primordial plants trigger a deep and ancient connection. Author Oliver Sacks wrote about the plant’s neurotoxic properties and nursed three cycads in his New York City apartment. The plants, he said, called to him “from a former world.” Others appreciate the plants as tough survivalists, bold and sculptural. Many value their rarity and expense. Living status symbols, cycads are the charismatic megafauna—the pandas—of the botanical world.

The massive seed cone of a Dioon merolae. Photograph by Kate Lain.

One early admirer was Henry E. Huntington, who was always on the lookout for ways to dazzle visitors and promote Southern California’s Edenic properties as he established the estate that today is The Huntington. In 1909, he spent nearly $5,000 (more than $100,000 in today’s dollars) on a lot of “rare and choice” cycads to plant near his mansion—now the Art Gallery. Many of these original plants survive today. “They’re like parrots,” notes Jim Folsom, the Marge and Sherm Telleen/Marion and Earle Jorgensen Director of the Botanical Gardens at The Huntington. “They live forever.”

Los Angeles was also home to one of the world’s most noted cycad experts. Until his death at age 84 in 2014, Loran Whitelock collected thousands of cycads on his modest hillside property in Eagle Rock, just northeast of Los Angeles. Whitelock, a health inspector, fell in love with the plants in Mexico in the 1960s and spent the next half-century studying, collecting, propagating, and writing about them. Two cycad species—Encephalartos whitelockii and Ceratozamia whitelockiana—are named after him. Whitelock’s 374-page tome The Cycads is considered the definitive guide to the plants.

Whitelock’s lush garden was one of the best private collections of cycads in the world. A widower with no children, Whitelock gave nearly 1,500 cycads to The Huntington, along with an endowment to care for them.

The task of moving the plants, some of them weighing more than 2,000 pounds, fell to Gary Roberson, lead project gardener for the cycad and palm collections at The Huntington. It was a gargantuan task.

Left: Cycads lining a brick walk in Loran Whitelock’s garden in 2014, shortly before The Huntington acquired his cycad collection. Photograph by Kate Lain. Right: Loran Whitelock and his wife, Eva, in front of their home. Photograph by Jim Folsom.

Roberson’s crew spent four months in the spring of 2015 digging up plants amid buried gas lines, easing them out of the ground with compact track loaders and teasing excess dirt from the roots by hand. Plants were given bar-code inventory labels, accession tags, and implanted with microchips to help keep track of their identities and provenance.

They were then transferred down Whitelock’s steep, narrow drive to trucks for transport. At The Huntington, a separate crew was waiting for them, holes already dug. Incredibly, all but 10 plants survived. “Most of the plants didn’t really skip a beat,” Roberson says. “They’re doing pretty well. They’re happy.”

Roberson has more recently been working on the new “cycad walk” designed by Folsom to showcase the plants. It runs behind the Art Gallery—within sight of Huntington’s original cycads—on what was a little-used, steeply sloped lawn. Here, the cycads are planted on terraced slopes in tribute to Whitelock’s hillside garden. “Loran’s garden was very exciting,” Folsom says. “Plant lovers who walked through it would drop their jaws. It would be fun if visitors could have that same feeling.”

Whitelock was a throwback to a time when descriptive science was not conducted by professionals but by educated laypeople, often doctors, who had time and money to travel widely to collect, Folsom says. Whitelock’s book, the so-called “cycad bible,” is laden with full-color photos and detailed descriptions. “It’s a huge contribution,” Folsom says. “There are several books on cycads, but nothing like his.”

Left: In the spring of 2015, a compact track loader eased one of Whitelock’s cycads out of the ground in his garden. Photograph by Gary Roberson. Right: Crew members Ramon Abelard (left) and Carlos Ceballos remove excess dirt from one of Whitelock’s cycads before it is transported to The Huntington. Photograph by Gary Roberson.

The Whitelock collection is especially valuable, Folsom says, because it is a founding population—many cycads growing in the U.S. today are progeny of Whitelock’s plants —and because it is the specific collection of plants upon which Whitelock’s book was written. “That’s beautiful,” Folsom says. “These plants are the living book.”

While cycads inspire collectors, they also beguile scientists because of their oddity. They look like palms but produce cones and are more closely related to conifers. They can grow in harsh deserts or rainforests, in bogs or on rocks, in full sun or full shade. They can live for a thousand years.

With no flowers to attract pollinators, these gymnosperms (or “naked seed” plants) dazzle instead with their cones, which can range from bright yellow to fire-engine red and weigh up to 90 pounds. They are the only type of gymnosperms that can generate their own heat, warming male cones by 20 degrees to repel insects living there toward more temperate female cones to spread pollen. And they have the largest sperm cells of any plant.

Cycads are also impressive survivors, having existed for nearly 300 million years, outlasting ice ages, volcanic eruptions, meteor strikes, and mass extinctions. (Sadly, human habitat destruction and poaching may wipe out what eons of epic devastations could not.)

Despite intense interest, there are yawning gaps in our scientific understanding of cycads. For example, cycads were long considered “living fossils”; they are common in depictions of dinosaurs. But a 2011 analysis revealed that while their ancestors coexisted with dinosaurs, the 300 cycad species alive today are much younger. These living species evolved 12 million years ago in what appears to have been one explosive burst.

Clockwise (from upper left), the pollen cone of a Dioon edule, the pollen cone of an Encephalartos woodii, the pollen cone of a Dioon tomasellii, and the seed cone of a Dioon merolae. Photograph of the Dioon tomasellii cone by Brian Dorsey; photographs of the other cones by Kate Lain.

Many outstanding questions about cycads center on their evolutionary history: how plants alive today are related to each other, why so many went extinct, and what is pushing today’s species to diversify. But determining how cycads are related—their phylogeny—has proven to be extremely difficult. A number of researchers, says Gregory, have chased this goal for a decade but failed “repeatedly and miserably” despite using the best technology available. Gregory knows such technology well; until his retirement, he was a scientist at biotechnology giant Genentech.

Scientists build phylogenies by grouping subsets of species based on which DNA variants they share. Work on cycads was frustrating because there is so little variability between species. “They’re turning out to be really pains,” Gregory says.

A cycad phylogeny was finally published in 2013, showing how the 10 genera of existing cycads are related. But many questions remain about the different genera, and about one in particular: Dioon. The Dioon cycads are interesting because seven of the roughly 15 species—which are distributed in Mexico from Sonora to Chiapas—are clustered in a small area around the Tehuacan Valley, and scientists are not sure when they diversified. Nor do they know why or how much genetic diversity exists in their populations. One species, oddly, is found only in Honduras.

Botanist Brian Dorsey came to The Huntington from the University of Michigan as a postdoctoral research fellow to answer some of these questions. But first, he needed to understand how the different Dioon species are related and if current species designations are even correct.

Dorsey’s previous work on Euphorbia required a consortium of 50 scientists and costly collecting trips to Madagascar. At The Huntington, getting samples is easier. “When I need more DNA, I just walk outside,” Dorsey says. “It’s like reading the collection.”

Left to right: Huntington intern Armando Serrano, a student at Pasadena City College, works to extract DNA from a cycad leaf (photograph by Lisa Blackburn); genetic data that Brian Dorsey analyzes for clues about the evolutionary history of the cycad genus Dioon ; a view of the Rio Santo Domingo canyon in Oaxaca, Mexico, the only place in the world where the cycad Dioon rzedowskii grows (photograph by Brian Dorsey); Mexican botanist Silvia Salas—who directs SERBO, a nonproÿt research and conservation organization in Oaxaca—and Tim Gregory, advisory board member of the University of California Botanical Garden, who has spent the past three decades studying and propagating cycads (photograph by Brian Dorsey).

But getting the genetic information out of the plants has been tougher. Unlike the genomes for humans and many plants, the full genome of a cycad has not been sequenced. “For other plants, you can go online and download entire genomes,” Dorsey says. “For cycads and Dioons in particular, there are not a lot of resources.”

So Dorsey had to start from scratch. As genetic sequencing was new territory for The Huntington, he first needed to equip the Mullin lab in the Frances Lasker Brody Botanical Center. Then he had to find useful genetic regions, or markers, that contain variations in order to unravel Dioon relationships. This required sequencing thousands of stretches of DNA from six Dioon species at The Huntington.

To do this, Dorsey collaborated with Chelsea Specht, a professor and botanist at the University of California, Berkeley, who—together with postdoctoral scholar Chodon Sass—has pioneered cutting-edge genetic tools to understand how gingers, bromeliads, and onions have evolved.

The two scientists, captivated by cycads as well, were happy to help Dorsey. Sass had worked on generating DNA sequences to use as “barcodes” for species identification. (Unscrupulous cycad traders often snip off leaves to make them difficult to identify by visual cues.) She had also become an expert at “next generation” gene sequencing techniques and those using microarray chips to capture thousands of genes from many species all at once.

It took Dorsey about a year of careful lab and computer work to identify the genetic markers he needed to try Sass’s technique. Though Dorsey is a botanist, much of his work on bioinformatics consists of sitting at his double-monitored computer, writing code to analyze giant files of genetic data. “I got into this profession to work in the woods,” says Dorsey, an outdoorsy Oregon native. “I rarely get there anymore.”

Dorsey has been helped in the lab by students from Pasadena City College. His current intern is Armando Serrano, who was born in Mexico but grew up in Japan, Queens, and Las Vegas before settling in Los Angeles.

Left to right: A field trip to the Sierra de Quila Flora and Fauna Protection Area in Jalisco, Mexico, to study Dioon in the wild; a Dioon tomasellii growing in an oak forest in the Sierra de Quila Flora and Fauna Protection Area (photographs by Brian Dorsey).

Interested in computer science, Serrano had taken a sprinkling of community college classes and supported himself as a waiter. But he hadn’t been inspired academically until he took a botany course at PCC. Though Serrano took the course merely to fulfill a credit, he ended up intrigued about plants and the use of computers to study bioinformatics.

Serrano now works at The Huntington regularly, extracting DNA from cycad leaves. It’s a difficult task because cell walls in the leaves are especially tough to break—Serrano uses a machine full of ceramic beads to pulverize them—and because the plant is full of enzymes and compounds that damage DNA once they are released. Serrano’s fallen hard for both botanical research and the cycads he works with. “I love them,” he says. “I’m completely absorbed.”

In his work, Serrano uses a wealth of scientific tools: pipettes, centrifuges, an enzyme extracted from bacteria in thermal geysers, and a machine that rapidly amplifies the DNA he’s extracted. He’s helping with Dorsey’s projects and also testing a technique to see if the sex of cycads can be determined from DNA—useful knowledge for conservation because some cycads take 20 years to produce the cones that show whether they are male or female.

While exciting, the work on cycads has also been frustrating. When Dorsey finally received the data from the markers he’d carefully created and sequenced at Berkeley, he hoped they would show clear variations, but he was bitterly disappointed. The data he got back was nonsense, with no patterns emerging.

The botanists put their heads together, trying to understand what went wrong. It’s possible the experiment was swamped by the immense cycad genome, which is 25 times larger than the human genome and, apparently, full of duplicate copies of genes and regions filled with seemingly meaningless repeats. “The cycad genome is huge and that’s really been a problem,” Dorsey says.

Luckily, Dorsey’s temporary position had turned into a full-time one, so he did not have to give up. He investigated other techniques and chose a highly efficient and precise way to pick through vast amounts of genetic information. The final sequencing was performed at the University of Idaho. It appears to have worked, and now Dorsey is analyzing how Dioon species are related and writing up the work for publication.

“This was definitely a difficult problem to tackle,” says Specht, who calls Dorsey’s scientific work based on The Huntington’s plant collections “a perfect marriage.” “Brian is at the right place at the right time. And he’s running with it.”

Jim Folsom—the Marge and Sherm Telleen/Marion and Earle Jorgensen Director of the Botanical Gardens—standing among several species of Dioon cycads in Loran Whitelock’s garden, 2014. Photograph by Kate Lain.

When the Dioon relationships are completely worked out, Dorsey will next turn to larger questions of biogeography and how the curious distribution of Dioon today may hold the key to understanding when and why the plants speciated, how much genetic diversity they contain, and how best to conserve them. Dorsey has taken two field trips to Mexico to study Dioon in the wild—one to Jalisco and Nayarit with the help of Jardin Botanico de Vallarta and another to southern Mexico. In Oaxaca, the plants grow at the interface of tropical deciduous forests and the pine/oak forests above them.

As Gregory had, Dorsey noticed strange patterns: two species might be separated by a single mountain ridge. A river may have one species growing down one branch and another species growing down a second branch. Why? One hypothesis: climate change, particularly global cooling during ice ages, drove the plants’ evolution by altering the altitudes at which the plants could grow. Plants may have moved up and down hillsides as climate changed, perhaps interbreeding and then separating into new species.

To test that theory, Dorsey is now planning to analyze samples of thousands of Dioon plants. The samples will be collected by Dorsey (under the proper conservation permits), Gregory, and Mexican botanist Silvia Salas, who directs SERBO, a nonprofit research and conservation organization in Oaxaca. In her work, Salas strives to educate local farmers, who often remove cycads in order to grow corn or allow collectors to take them. She’s planning a project to document the use of starch from Dioon seeds to make tortillas in an indigenous community in northern Oaxaca. “We talk, talk, and talk with them,” Salas says. “If local people understand how special these plants are, they will protect them.”

Folsom is hoping The Huntington can help with conservation work by propagating the plants for reintroduction in the wild and through a “captive breeding program” that might sate the demand of cycad collectors and lower prices so the plants are not plucked from their native soil. “I like the fact that plants are seen as so wonderful because they’re rare, but that rarity destroys them in nature,” Folsom says. “I’d actually like to destroy the market.”

Usha Lee McFarling is a Pulitzer Prize–winning freelance writer based in South Pasadena, Calif.