Posted on Sat., April 1, 2017 by

Two 15th-century panels from an Italian wedding chest tell a tale of passionate love

Catherine Hess, interim director of the Art Collections and chief curator of European art, stands beside a mid-16th-century Italian cassone of carved walnut. On the wall is the second panel of Michele Ciampanti’s Antiochus and Stratonice, ca. 1470. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

Newly married couples in 15th- and 16th-century Italy—like newlyweds today—could expect to receive a pile of wedding gifts. One of the most common gifts was a cassone, or big box, used to store such household goods as books or linens. Often given in pairs, these oversized wooden boxes were decorated to celebrate the happy union.

The Huntington owns two remarkable panels that come from a pair of cassoni made in Tuscany in the late 1400s. Such wedding chests were useful pieces of furniture, open and shut daily—not to mention kicked by children, bumped by ham-handed movers, and damaged beyond repair by water and insects. The original chests that held The Huntington’s panels have disappeared, but the panels themselves were carefully preserved and ultimately framed (by some unknown person) as paintings. Arabella Huntington purchased them in 1914, the year before she married Henry E. Huntington.

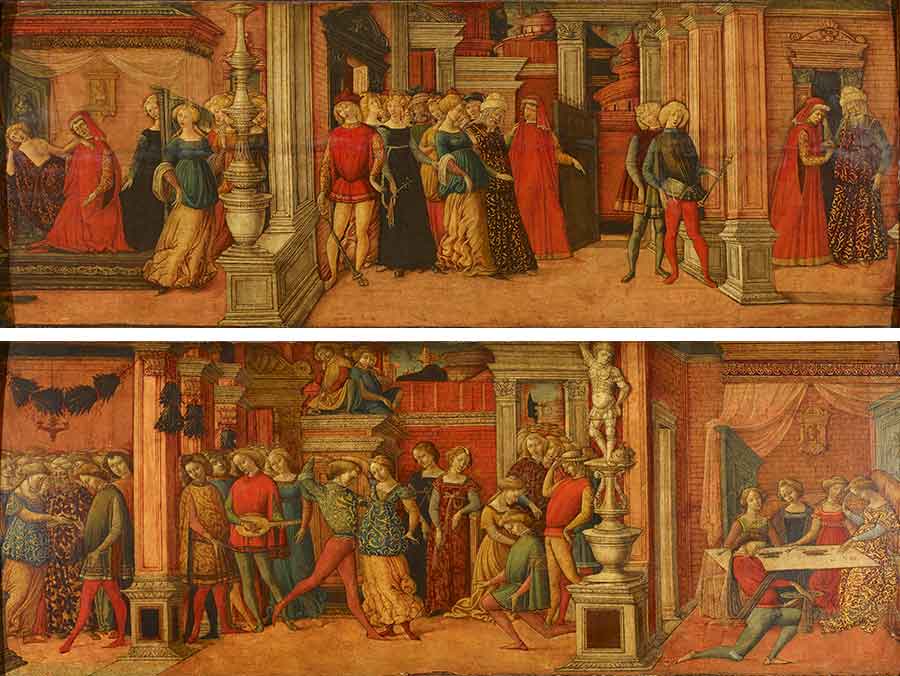

The panels’ six scenes—three per panel—depict a continuous narrative meant to be read from left to right, like a comic strip. They tell the real-life love story of Antiochus and Stratonice, which can be found in the works of a number of ancient writers—including Plutarch, Pliny, and Hippocrates.

The story begins when Antiochus, the son of Apama and Seleucus—king of Syria in Macedonia from 305 to 281 B.C.—develops a strange and terrible illness after his father marries a much younger second wife, Stratonice. The king calls upon his physician Erasistratus to diagnose his son’s ailment. On the left side of the first panel, we see Antiochus languishing in bed while the doctor, in red cloak and hat, takes his pulse; Stratonice, in a green tunic and white skirt, glides by and glances back at Antiochus.

Known for his early understanding of the function of the heart and circulatory system, Erasistratus notices that Antiochus’ skin grows warmer and his pulse quickens only when his stepmother enters the room. The physician identifies the disease as lovesickness, which Antiochus has kept secret, preferring to pine and waste away in silence.

Recognizing the tricky situation, Erasistratus decides to try an unusual remedy to save the young man’s life. In the very center of the panel, we see the physician approaching the king, dressed in brocaded robes and walking with his young wife. On the right side of the panel, in a private setting, the doctor tells the king about his son’s incurable disease. In response, with a gesture both puzzling and generous, Seleucus saves his son’s life by giving up Stratonice and allowing his son to marry her.

Michele Ciampanti’s Antiochus and Stratonice, ca. 1470, tempera on panel. The six scenes—three per panel—depict a continuous narrative meant to be read from left to right, like a comic strip. The Arabella D. Huntington Memorial Art Collection.

In the second panel, we see the marriage of Antiochus and Stratonice, officiated by the king, who appears on the left under a garland, while the two newlyweds dance at their wedding party in the center, accompanied by musicians and guests. However, while Antiochus is shown on the right lowering on bended knee, another man in a brocaded vest twirls Stratonice. What to make of this interloper? Was such a dance move common or does it somehow reflect Stratonice’s remarkable passivity in the story—passed from one man to another without a peep?

A scene of lavish dining to the right takes place before a bed with drapes, perhaps foretelling wedding-night activities to follow. Or has the wedding night already taken place? Is it possible to deduce from her puffy dress that Stratonice is already pregnant, as she dines with her girlfriends? Indeed, it appears that the youth kneeling before them presents a so-called desco da parto—a specially painted tray that, during the Renaissance, served as a fancy gift to a woman celebrating the birth of a child.

In Renaissance literature, the story of Antiochus and Stratonice was occasionally paired with the tale of Ghismonda and Guiscardo from Bocaccio’s Decameron, in which a father kills his daughter’s lover, impelling the daughter to commit suicide. The former story celebrates a father’s munificence, while the latter tells of a father’s vengeful rage.

Such an abstruse pairing of the two stories—one peaceful, the other violent—might also help explain the appearance of a sculpture depicting David with the head of Goliath between the wedding dance and the final scene in The Huntington’s cassone panel. To literary cognoscenti of the time, David’s violence—like the father’s violence in the tale of Ghismonda and Guiscardo—might have hinted that Antiochus’ story would have ended badly if his father had been less generous. Stratonice’s gesture in the final scene—in which she touches her hand to her forehead—might be read as a visual “Whew!”

The Huntington’s cassoni panels are among the earliest post-classical depictions of the narrative. Before scholars secured the identity of the painter—Michele Ciampanti, who was active in Lucca from around 1463 to 1510—they referred to him simply as “The Stratonice Master.”

Based in history but transmuted by legend and literature, the story of Antiochus and Stratonice was perhaps most honestly celebrated by Petrarch in his poem The Triumph of Love: “To give another his beloved spouse: O utmost love, unheard-of courtesy!” Is it a coincidence that Arabella Huntington—who married Collis Huntington in 1884 and then, three decades later, his nephew, Henry—bought this painting the year before she remarried?

Catherine Hess is interim director of the Art Collections and chief curator of European art at The Huntington.