Counting Extinction

Posted on Sun., April 1, 2018 by

The last observations of a small Hawaiian bird

Pencil sketch of a Kaua‘i ‘O‘o by H. Douglas Pratt.

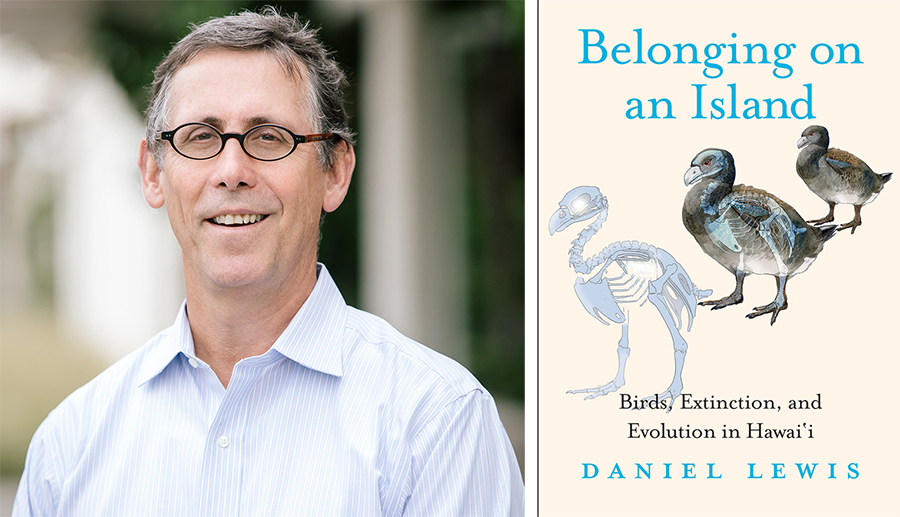

In Belonging on an Island: Birds, Extinction, and Evolution in Hawai‘i (Yale University Press, 2018), Daniel Lewis, Dibner Senior Curator for the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington, takes readers on a 1,000-year journey as he explores the Hawaiian Islands’ beautiful birds and a variety of topics, including extinction, survival, conservationists and their work, and, most significantly, the concept of belonging. Lewis, an award-winning historian and globe-traveling amateur birder, builds his lively text around the stories of four species—the Stumbling Moa-Nalo, the Japanese White-Eye, the Palila, and the Kaua‘i ‘O‘o.

Lewis offers innovative ways to think about what it means to be native and proposes new definitions that apply to people as well as to birds. Being native, he argues, is a relative state influenced by factors including the passage of time, charisma, scarcity, utility to others, short-term evolutionary processes, and changing relationships with other organisms. His book also describes how bird conservation started in Hawai‘i and the naturalists and environmentalists who did extraordinary work.

In the following excerpt, Lewis draws from papers in The Huntington’s collections to describe encounters that the field biologist John Sincock had in the 1970s with Kaua‘i ‘O‘o, a bird species teetering on the brink of extinction.

Field biologist John Sincock in the forest with a tape recorder, from The Huntington’s Scott Collection.

The Kaua‘i ‘Ō‘ō, Moho braccatus, seemed to have gone extinct during the 20th century, and more than once. But its survival, and the details of its life history, were not documented until field biologist John Sincock came along. He had been working for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service for four years on Kaua‘i before spotting the ‘Ō‘ō. It was a Wednesday—the 26th of May, 1971, around 9:50 in the morning in the Alaka‘i Swamp. Sincock was out doing forest bird counts. Suddenly, he heard a hair-raising sound: the call of an ‘ō‘ō. There, within 15 feet of him, were a pair of the birds, flitting around in the lapalapa and ‘ōhi‘a trees. They had last been heard and recorded in 1968 by Ian Atkinson, a University of Hawaii grad student, who recorded one at the Koaie cabin area on a wet and windy day, but the bird was not seen, and had not actually been sighted since September 1963, and despite a few unconfirmed reports in recent years, was thought to be extinct. Sincock watched them for a half-hour with his binoculars. Beyond his field report to his boss at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland 12 days later, and an article in the Kaua‘i newspaper The Garden Island in early June, no contemporary record exists of this encounter. For the first time, Sincock had left his camera behind; the light meter had been low on battery power. He returned to the site late in the afternoon, where he saw them again, feeding on ‘ōhi‘a blossoms, foraging briefly in a Broussaisia umbel, and frequently scratching and grooming themselves. The birds were relatively small—about eight or nine inches long—the smallest of the family of the five birds (at least those known from the historical record) to which it belonged. Its diminutive nature was reflected in its Hawaiian name: ‘Ō‘ō ā‘ā, or “dwarf ‘Ō‘ō.” The smallest of five allied species that had lived on other islands were all long extinct.

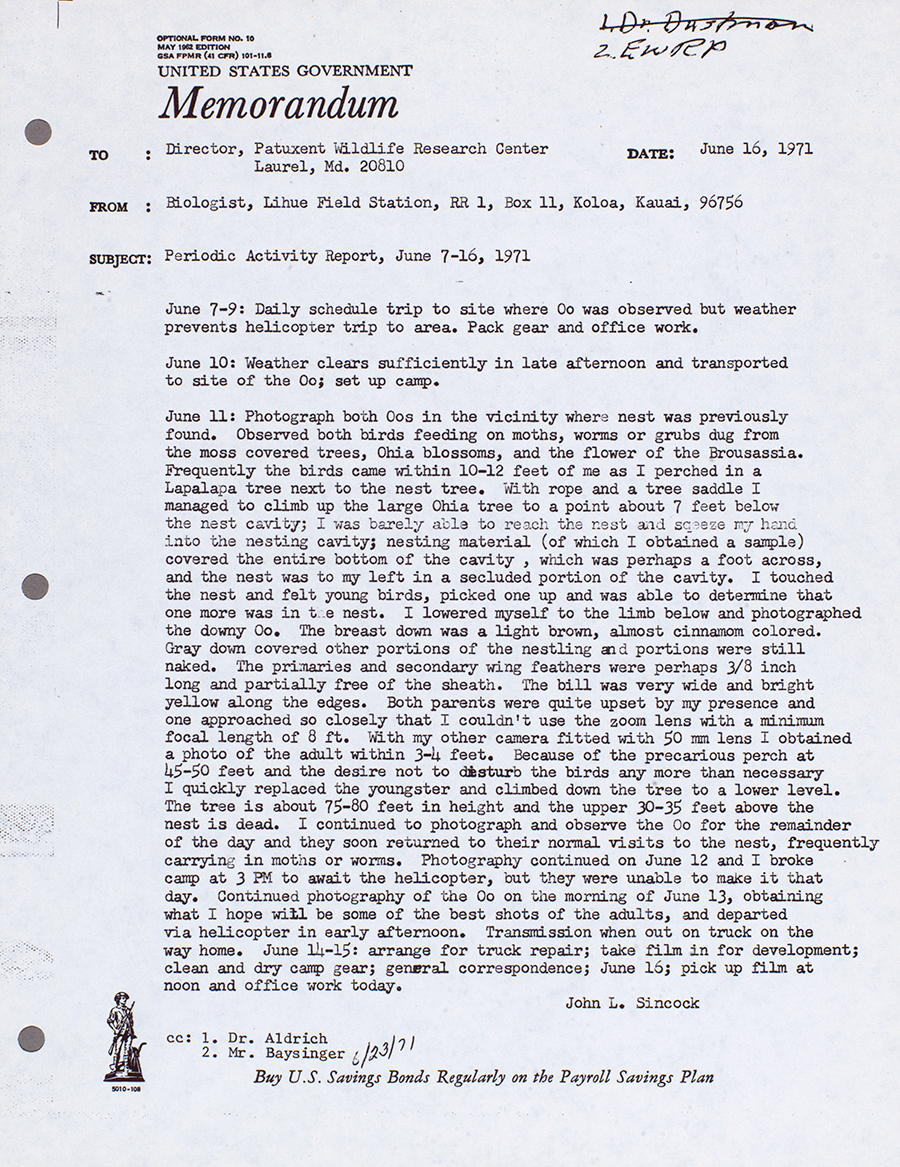

A 1971 memorandum by John Sincock in which he describes his encounter with a pair of Kaua‘i ‘O‘os and his discovery of a nest with young birds in it.

Returning the next day in heavy rain, he set up mist nets in an attempt to capture the birds, probably to take measurements and band them. The birds watched him with interest but had the sense not to fly into the nets, and frequently sounded their melodious call.

Sincock made his next trip with his wife Renate on May 31, five days later—now loaded heavily with still cameras and 8mm movie cameras, and again spotted the birds, this time in a heavy downpour. Renate took many still photos—in the process becoming, as the Kaua‘i newspaper noted a week later, “probably the first woman in history to photograph an ‘ō‘ō.” These were the first photos ever taken of the bird. She also captured about five minutes of what Sincock later described in a memo to his boss as “fairly good” film, and a couple of “fair” 35mm color slides. In subsequent weeks and months, Sincock returned to the area regularly, flown by his friend and helicopter pilot Jack Harter each time. During one visit, he climbed up as close as he could get to the nest for photographs—about 50 feet off the ground, in the large ‘ōhi‘a tree where the birds were nesting. “I touched the nest and felt young birds, picked one up and was able to determine that one more was in the nest,” he wrote.

Kaua‘i ‘O‘o, 1890. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Cullman Library.

Perhaps knowing every observation was critical for the species’ future survival, and that the pair might well be the only ones left on the planet, he recorded every detail of their feeding, flight, and call activities, including the size of their nesting cavity, descriptions of the birds’ feathers and bills, and other details, including the plumage of the juveniles. He also found and took an apparently abandoned ‘Ō‘ō nest and sent it to his bosses at Patuxent. He wasted no time in contacting local and national media, including National Geographic.

The first time he actually heard the bird, though, occurred before he saw it, less than a year after his arrival in the islands—probably on the afternoon of May 5, 1968, as recorded in his memo to his boss in Maryland. “Heard a loud call, frequently repeated ‘took’ ‘took’ in the slopes leading to Koaie Valley which I believe was an OO—at least that is the way Munro describes the call of the OO and the call I heard could be described in no other way. Most often the call was a single, loud clear ‘took.’” He thought he probably heard the bird again the next month as well. So, he would have remained attuned to the possibility of the bird’s existence, and by process of elimination alone he very likely correctly identified the call in 1968, being very familiar with recordings of Hawaiian bird songs and calls by then, as well as having experience gleaned from many hours in the field.

John Sincock, left, and Mike Scott in the back of a pickup truck, 1978. Photograph courtesy of James Jacobi.

The birds appeared frequently during the early and mid-1970s, mostly in the Alaka‘i, and he took extensive photographs of them. Sincock, fellow Federal biologist Mike Scott, and Fred Zeillemaker, the manager of Kaua‘i’s National Wildlife Refuges, made extensive audio recordings throughout the summer of 1975, and at least once in the summer of 1976. Not only had a handful of the birds survived, but based on courtship activities, appeared to be attempting to breed. “We had fantastic looks at several ‘Ō‘ō including a pair heavily engaged in courtship activities,” Mike Scott recounted to me.

Several firsts took place in the next several years, including very important extensive documentation of the bird’s life history. “We were fortunate to be the first ever to see a young oo bird just out of the nest and photographed the adult feeding it,” Sincock wrote in 1973. Some of his details of the bird’s habits are potentially of great value, especially if the bird does, improbably, somehow survive today. The birds spent much of their time feeding throughout the valley, he wrote to Erickson in 1974. “Frequently they land on the upper dead branches of Ohia trees, sit side by side, and give their melodious call. Calling starts at just about 6 AM and ends at about 7 PM; often calling slacks off from 11 to 3. They are far more active during the brief periods of 5 to 10 minutes of sunshine, and during the frequent periods of cloud cover and rain they are quiet and difficult to locate. Their beep-beep call, heard in previous years was not heard during this trip and must only be used during their active nesting.”

Left: Daniel Lewis, Dibner Senior Curator of the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington. Photograph by Dana Barsuhn. Right: Cover of Belonging on an Island: Birds, Extinction, and Evolution in Hawai‘i (Yale University Press, 2018).

The bird was down to a very small number of surviving examples by the mid-1970s. Sincock noted in the summer of 1975, “I fear that the population of oo may be even lower than my guess of possibly two dozen. This one location of 2 or maybe 3 oo is all that I can find.” Sincock would see the birds many times in subsequent years, but never more than two at a time; perhaps they were the same pair. The bird was last seen in 1985 and last heard in 1987. Hurricane Iniki, Hawai‘i’s most damaging hurricane on record, devastated the entire island of Kaua‘i in 1992 and would most likely have decimated any surviving birds. After many thousands of years, the bird was gone.

Daniel Lewis is Dibner Senior Curator of the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington and research associate professor at Claremont Graduate University.