Examining The Blue Boy

Posted on Sun., April 1, 2018 by

A paintings conservator and an ear surgeon talk shop

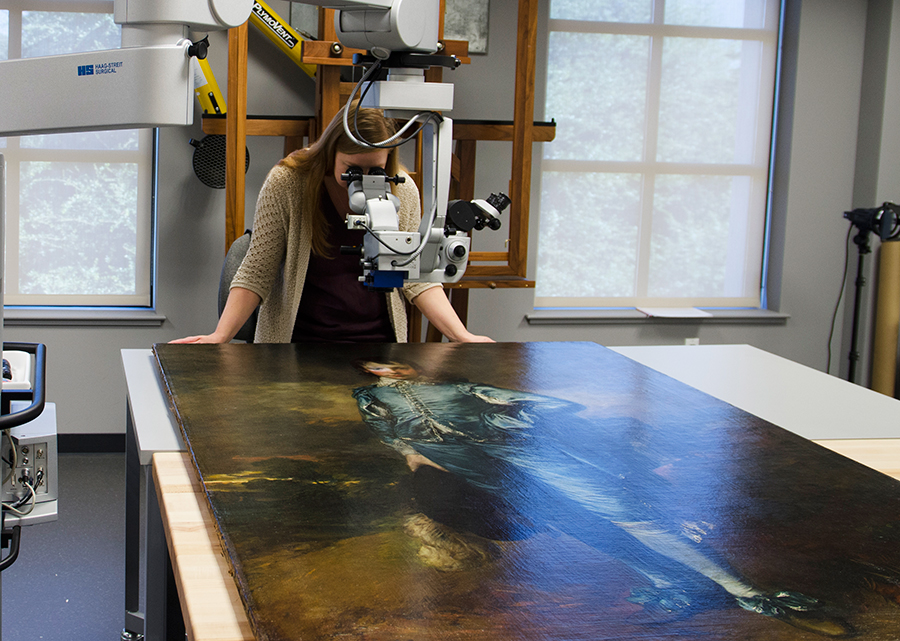

The Huntington’s senior paintings conservator, Christina O’Connell, examines The Blue Boy, made around 1770 by the English painter Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788). Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

Thomas Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy (ca. 1770) may well be an icon of Western art and one of the most beloved attractions at The Huntington, but now that it is nearly 250 years old, this epic portrait is in need of some tender loving care. The edges are brittle, and in some places, the paint is starting to lift and flake away. The Blue Boy has had some touch-up work done in the past, but until four years ago, The Huntington did not have a full-time paintings conservator on staff. With Christina O’Connell in that role, The Blue Boy is finally about to get the full makeover he needs.

Dubbed “Project Blue Boy” and funded by a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project, the two-year technical examination and conservation treatment began in the fall of 2017, when the painting underwent preliminary conservation analysis in O’Connell’s lab. An important part of “Project Blue Boy” is that many stages of treatment will be presented from Sept. 2018 to Sept. 2019 in the Thornton Portrait Gallery, where the painting traditionally hangs.

Before O’Connell could embark on “Project Blue Boy,” she needed the right tool with which to conduct diagnostics—a powerful microscope. The small, five-decades-old microscope in her lab just wasn’t up to the task. Here’s where serendipity played a role. A conversation between a Huntington staff member and Board of Overseers member Barbara House sparked a curious connection: Barbara’s husband, John, is a renowned ear surgeon, of the House Ear Clinic in Los Angeles. He uses high-powered microscopes all the time in his delicate work. Could a surgical microscope do the job of art conservation? In follow-up conversations, House and O’Connell set off to find out, with House ultimately putting in motion the loan of a Haag-Streit surgical microscope that has made the process of The Blue Boy’s restoration not only possible but much easier.

What surprised both O’Connell and House—who work in such different areas—was how much they had in common in the work that they do. For Huntington Frontiers, Pulitzer Prize–winning science journalist Usha Lee McFarling recently sat down with the pair as they talked over the project. The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

McFarling: John, how did you get involved in this project?

House: We knew the project needed a microscope, and I thought I could help. I went to a couple of microscope vendors we work with and, as it turned out, they were happy and eager to help and have been incredibly cooperative. Haag-Streit has given us, on a long-term loan, this wonderful microscope.

McFarling: Christina, what kinds of things did you tell Haag-Streit you needed that might not be important to medical users like John?

O’Connell: I jumped right into talking shop with the Haag-Streit reps, and they were fascinated because they hadn’t worked on a project that was art related. We spent a lot of time discussing the light source because I needed one that did not generate heat and let us see the painting’s true colors. I need to be able to distinguish between what paint is original and what’s not. When the reps saw our laboratory microscopes, they said, “Oh, we can do so much better.”

While O’Connell looks on, renowned ear surgeon John House peers through a Haag-Streit surgical microscope at The Blue Boy. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

McFarling: How important is the new microscope to this project?

O’Connell: Well, when we are diagnosing The Blue Boy, he can’t tell us his medical history or his treatment history. We have to look carefully at both the painting and historical documents to find the information we need. Having a microscopic view of the surface is better for evaluating whether the painting is stable or not because you can really see how the cracks look or if paint is lifting. These are things you might miss without proper magnification.

House: Absolutely. The microscope gives you not only the magnification, but also the illumination focused exactly where you need to look. It makes me think about what our ancestors went through when they were looking at these paintings. They may have used candlelight or sunlight, and they didn’t have the magnification we have. In our field, people were trying to do ear surgery with gas lamps and no magnification, looking through a little tiny instrument into the ear. When the microscope came into play, it dramatically opened many doors with respect to what we could do surgically in the tiny structure of the ear. Back in the 1800s, the things that they were doing were amazing, considering the tools they had.

McFarling: The microscope is large enough to extend over this immense painting. What else about it helps you do your work?

O’Connell: There’s a controller device that I can activate with my foot to move the microscope, adjust magnification and focus, and capture images. Since it’s a foot control, I can do all this while my hands keep working.

House: And she can adjust the working distance. Say she’s really close in and her brush hits the microscope, she can just pull and the microscope will stay in focus as she moves back. With older microscopes, you had no choice on the working distance. She can go way back or be in close and stay in focus.

McFarling: Your work couldn’t be more different—but are there similarities in what you need from a microscope, whether you are viewing a human ear or a Grand Manner portrait?

House: Having 3-D vision is very important. The painting is flat, but I’m sure there are little ridges and things that you really need to view closely, to get the idea of their shape. In my case, we have to have 3-D in order to have depth perception because I put an instrument in the ear, and I don’t want to go too far with my instrument.

O’Connell: Exactly. These are very much composite objects, and there is more texture than you would think. When there are areas of paint that are lifted up, having that depth perception is important so that I can see how far it’s lifting and can carefully watch it go back down to plane, which happens during treatment.

Christina O’Connell takes a close look at The Blue Boy through the surgical microscope. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

McFarling: What else excites you about this microscope’s capabilities, and the project?

O’Connell: We can photograph through the microscope and also videotape. Documentation is a very important part of our work, ethics, and practice, so having this capability to take images is very important. We couldn’t do any of that imaging with our other microscope.

House: And it’s perfect because you can connect the microscope to a large, high-resolution, flat screen as Christina works on it in the public gallery. I was on a trip in Florence with several members of The Huntington a few years ago, and we toured a conservation lab where a woman was restoring a painting on a scaffold using magnifying glasses. We were standing way back and looking—it was amazing to watch her work—but we really couldn’t see what she was doing. So, it’s very exciting to think about doing this conservation with a microscope and a screen so the public can see exactly what Christina sees. It will be a tremendous education for anyone interested in the conservation of paintings. It’s like when we’re teaching ear surgery. We teach, and the students watch the ear surgery, and what they’re seeing is exactly what I’m seeing.

McFarling: Christina, tell me about some of the things you notice when you look at The Blue Boy through the microscope.

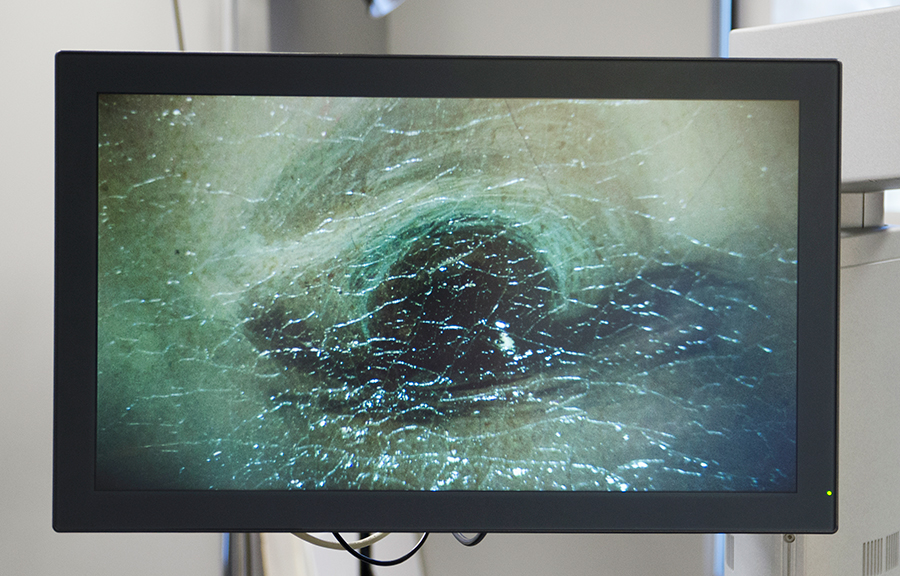

O’Connell: You’re definitely getting a closer view of the tricks that the artist used to represent a 3-D world. You can see the paint, but there are some areas where I can actually see the pigment particles, which means Gainsborough was sometimes using more coarsely ground particles that reflect light differently. He understood the physical properties of the materials he was using to create his paintings. It’s amazing to see how a little dab of paint is the highlight in The Blue Boy’s eye, whereas when you stand back, it just blends together. After you have worked on a painting, you get to know it so well that you become attached to it. You know the surface and every bit of it.

McFarling: Tell me about some of the work you are going to do to repair The Blue Boy and reveal some of his original vibrancy.

O’Connell: I can see the painting has been treated many times in the past, and we’re still going through all of our data to figure out if we can have a better estimate of how many times or what has actually been done. But there are some areas where Gainsborough painted the background very thinly, and there are areas where people have scrubbed the painting in the past and rubbed off some of the paint. We call that abrasion.

House: Oh, that hurts.

O’Connell: I know. It hurts me, too. I can see uneven cleanings where people have started to take things off and stopped. In some ways, I’m glad they stopped because, if they were going to cause further abrasion, it’s better they stopped and left it uneven.

Magnified detail of one of The Blue Boy’s eyes, as it appears on the surgical microscope’s display screen. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

McFarling: It’s almost like you have to go in and repair someone else’s surgery.

House: We do that all the time.

McFarling: Can you talk about the color of the painting and the haziness? It almost seems as if The Blue Boy is a bit under the weather, no longer sporting his healthy pallor.

O’Connell: There are many layers of varnish and old inpainting—the painting a conservator does to restore a damaged area—that are covering The Blue Boy, and as those materials age over time, they become cloudy and discolored, and they affect how the painting reads. The contrast between light and dark is a little bit imbalanced when you have degraded layers on a painting. Removing those will reveal Gainsborough’s brushstrokes and colors, and then putting new varnishes on without all of those layers in the way will saturate the colors and create that contrast between light and dark again.

House: You’re going to put the varnish back on?

O’Connell: Varnishes were meant to be put on as a temporary and protective layer that could be removed later. We have a lot more varnishes to choose from now compared to what Gainsborough had in his time. And any inpainting I add or repairs I make will occur on top of the new varnish, so it all can be safely removed later—if later treatments call for that. That’s part of our guidelines of practice and code of ethics. I am not going to permanently alter this painting.

House: You’ll do this in very small areas at a time?

O’Connell: I will roll a tiny cotton swab on a toothpick and work on a tiny area to evaluate it. The work proceeds very slowly and carefully. That’s why I need to understand all the different layers, so I can carefully unpack and move through those layers in a controlled way. If anything’s not working out the way we predict, we can stop.

McFarling: John, I see you shaking your head. What are you thinking?

House: I’m thinking: it’s going to take a long time. That’s a big painting.

O’Connell: One of the mantras in my field is, “There’s no such thing as fast conservation work.”

John House and Christina O’Connell talk shop. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

McFarling: That’s different from surgery, when you have a patient under anesthesia.

House: Yes, you have to move right along.

McFarling: Surgeons obviously need good hands. Is that something the two of you share?

House: Certainly.

O’Connell: Steady hands. Hand skills.

House: In a way, I think your work is more difficult because you can’t brace your hands very well. You’re almost freehanding. When we’re operating, we’re basically bracing our hands—if the patient were to move, we want to make sure we move with her.

McFarling: John, how was it seeing The Blue Boy through the microscope? Did that increase your appreciation?

House: This whole project has increased my appreciation. Seeing it through the microscope is like looking at a different world, really. It was a thrill.

Usha Lee McFarling is a Pulitzer Prize–winning freelance writer based in South Pasadena, Calif.