The Ghostly Return of Hamlet

Posted on Wed., Oct. 16, 2019 by

The Huntington's copy of the first edition of the play upended the play's history

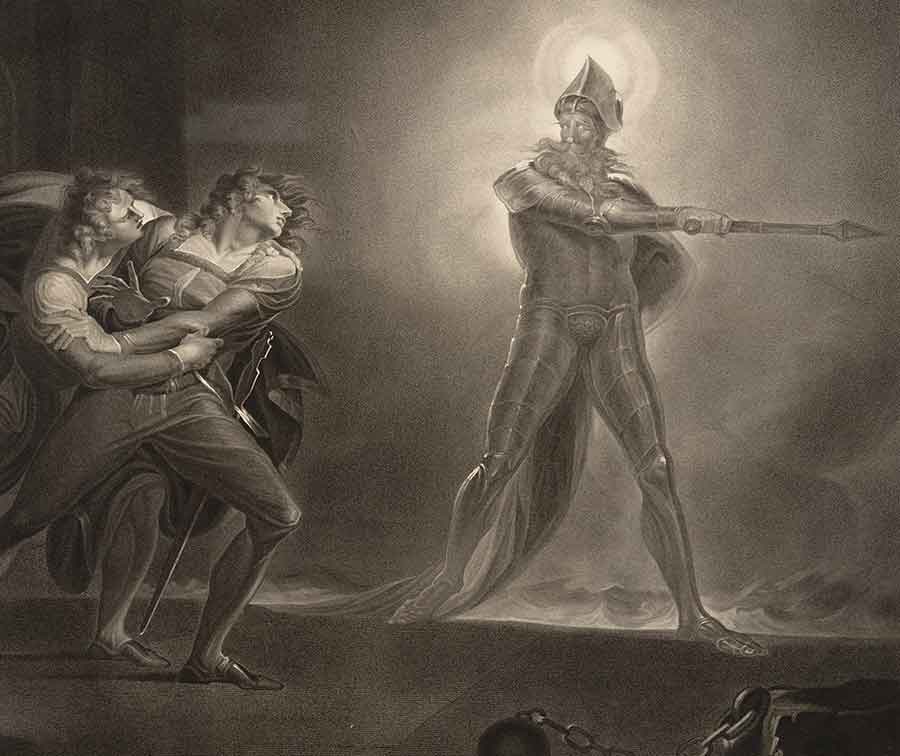

Hamlet and the ghost of Hamlet’s father in Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Act I, Scene IV (engraving based on a painting by Henry Fuseli), from A collection of prints, from pictures painted for the purpose of illustrating the dramatic works of Shakespeare, by the artists of Great Britain, London: John and Josiah Boydell, 1805.

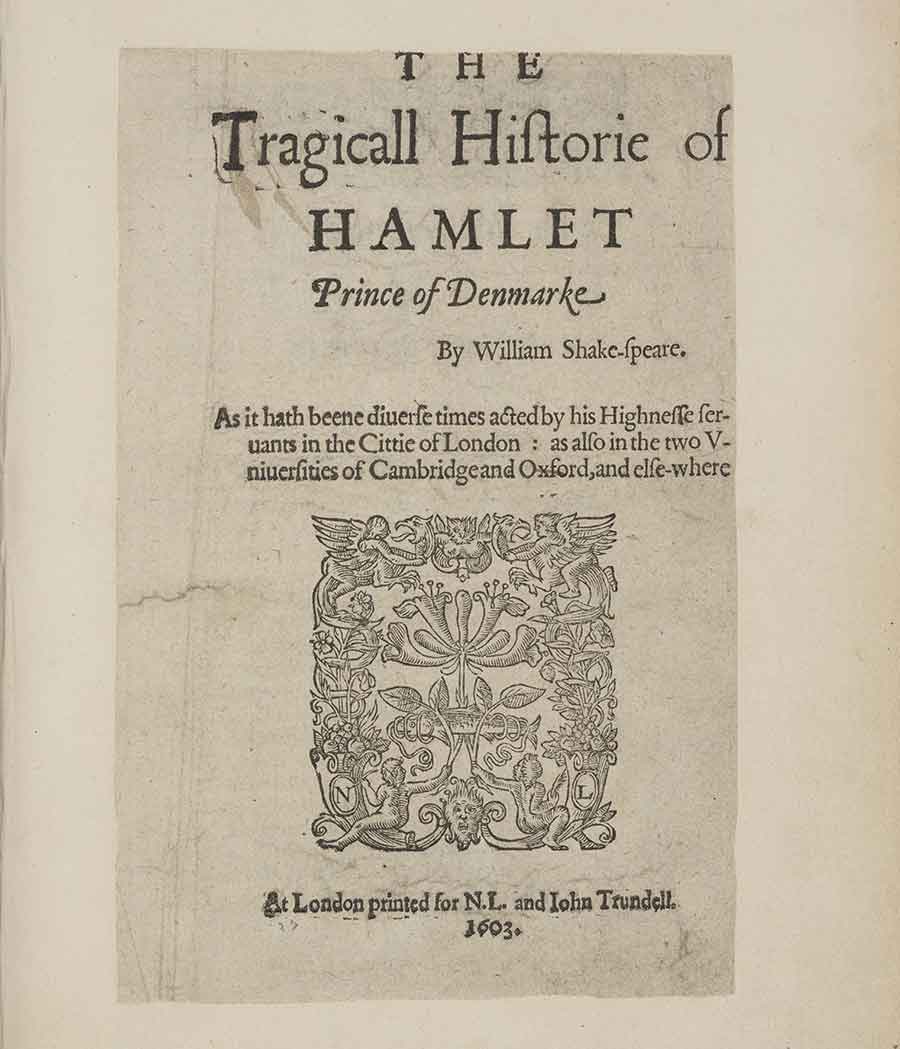

In 1914, Henry E. Huntington acquired from the Duke of Devonshire a collection of English drama that included one of two surviving copies of the first edition of Hamlet (1603)—also known as the first quarto (Q1), or “bad quarto.” This version of the play varies significantly from the one commonly read in school and performed onstage today. The Huntington’s copy, the only one that includes the title page, was discovered 200 years after Shakespeare’s death in a manor house in Suffolk, England. In Hamlet After Q1: An Uncanny History of the Shakespearean Text (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), Zachary Lesser, professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania, examines how the improbable discovery of Q1 has forced readers to reconsider accepted truths about Shakespeare as an author and about the nature of Shakespeare’s texts. The following excerpt from the introduction to the book is reproduced with the permission of University of Pennsylvania Press.

Two centuries after the death of its author, William Shakespeare’s greatest play was changed forever. In 1823, Sir Henry Bunbury found an old book, “a small quarto, barbarously cropped, and very ill-bound,” in a closet of the manor house of Great Barton, Suffolk. Or maybe he had found it two years earlier in the library, or in a closet in the library; Sir Henry could never seem to recall. He had recently inherited the manor and was taking an inventory of his new holdings, which fortuitously led him to this book that otherwise might have continued to rest on the shelf unknown and unread. Or maybe he was inspired to scour his shelves for rare books after reading The Library Companion by the self-described bibliomaniac Thomas Frognall Dibdin; so Dibdin claimed, anyway, providing a third possibility for the discovery. Since Barton Hall was destroyed by fire in 1914, it is now impossible to know exactly where this remarkable book was found. But the story I will tell deals repeatedly with loss, destruction, and reconstruction.

Barton Hall, where The Huntington’s copy of Q1 was discovered, after the hall was destroyed by fire in 1914. Reproduced with kind permission of Bury St. Edmunds branch of Suffolk Archives, shelf mark HD526/11/9.

Bunbury’s “small quarto” contained twelve of Shakespeare’s plays, nearly all in their first editions, including Romeo and Juliet, The Merchant of Venice, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and several of the histories. Such a compendium would today be worth a fortune, had it not been disbound sometime later in the nineteenth century while in the collection of the Duke of Devonshire, the pages of each play “barbarously cropped” once again to be inlaid in fine paper and rebound. Despite the obvious value of these Shakespearean first editions, however, in an age when antiquarian book collecting was a relatively new gentlemanly pursuit and when numerous Shakespearean play- books were still in private hands, this “ill-bound” book would not have created such a stir had it not included one oddity.

This was a copy of the first quarto of Hamlet (Q1), published a year prior to the earliest text of the play then known and, at the same time, the unique example of the edition. What Bunbury had found was recognizably Hamlet, but it was radically different from the play that was, already by 1823, the most highly prized and revered work of English literature. Bunbury surmised that Q1 and the other plays in the volume had been purchased and bound together by his grandfather, Sir William Bunbury, “who was an ardent collector of old dramas.” If so, one wonders how such a collector could have missed the incredible rarity in the group. But Sir William seems to have had no idea what he had on his hands; he drew no special attention to the book, and it lay quietly on that shelf in Barton Hall for two more generations. Nor apparently did Sir Henry value the book highly enough: he exchanged it with the booksellers Payne and Foss “for books to the value of £180,” but they quickly sold it to Devonshire at a tidy profit. Before completing this sale, however, Payne and Foss sought to satisfy “the intense curiosity which this book has raised in every literary circle” by issuing a reprint edition from their shop at 81 Pall Mall. The 1825 publication of The First Edition of the Tragedy of Hamlet, By William Shakespeare created huge excitement in the press and brought Q1 to general notice.

The title page of The Huntington’s Q1 Hamlet , 1603.

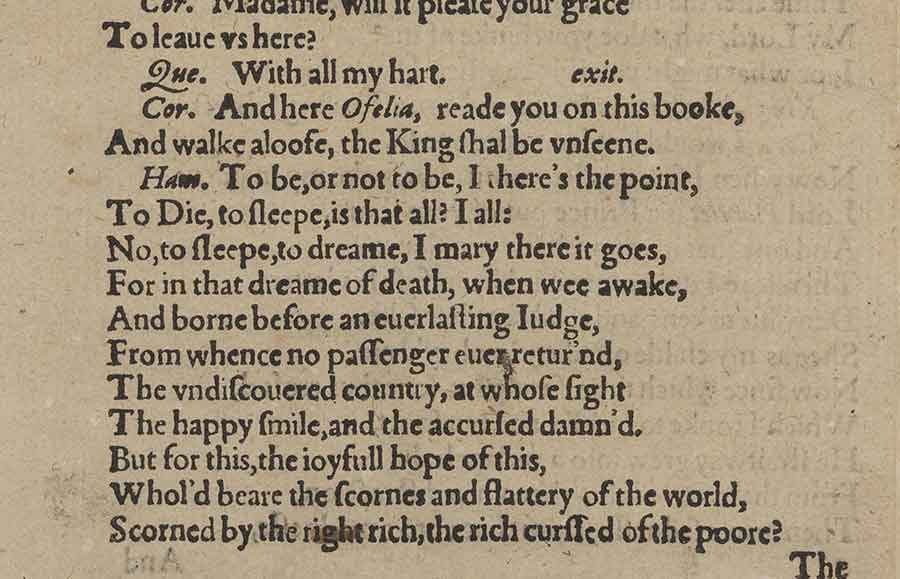

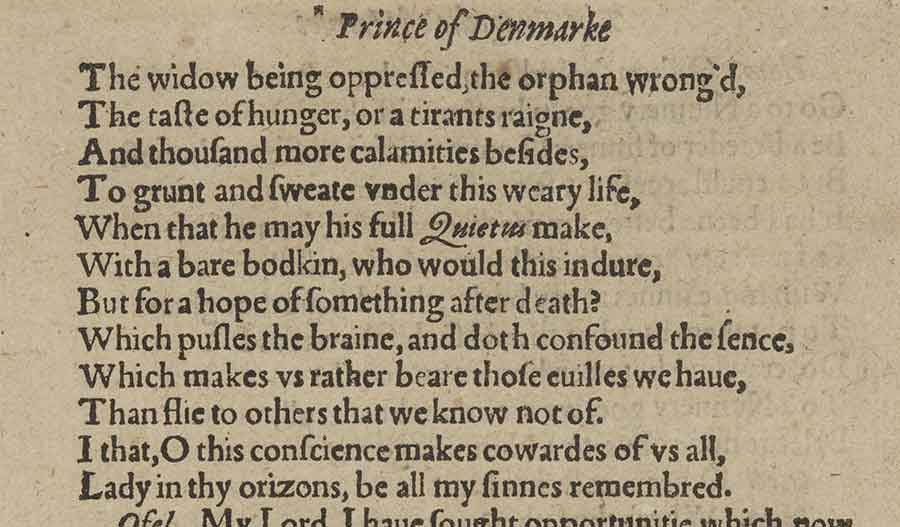

In what seems to have been the earliest public report of the discovery, the Literary Gazette told its readers that Q1 contained “new readings, of infinite interest; sentiments expressed, which greatly alter several of the characters; differences in the names; and many minor points which are extremely curious.” This Hamlet was about half the length of the familiar version, and to some its poetry seemed only a “poor version” of the speeches they already knew, although others found many new “lines of great beauty.” Some of the most famous lines, in fact, were different. Instead of asking, “To be, or not to be, that is the Question,” Hamlet pondered, “To be, or not to be, I there’s the point,” before going on to speak explicitly of God’s judgment that consigns us to an afterlife in heaven or hell. Hamlet’s last words were likewise transformed: the rest was no longer silence, as Hamlet piously implored “heauen to receiue my soule” before dying. The plot followed broadly the same trajectory, but with a number of “extremely curious” variations: “To be or not to be” and the ensuing “nunnery scene” with Ophelia (Ofelia in Q1) were transposed to an earlier point in the play; in the so-called closet scene, the Queen (here called Gertred) explicitly denied any knowledge of the murder of Hamlet’s father and vowed to assist her son in revenge, shedding new light on a long-standing debate about her character; and in a scene with no parallel in the familiar version of the play, Horatio told the Queen of Hamlet’s adventures at sea, and the two proceeded to conspire against Claudius. Polonius’s name had oddly become Corambis, his servant Reynaldo had turned into Montano, and scattered throughout the text were numerous other differences large and small, at the broad level of plot and character and at the narrow level of single word choices. “From these variations,” the news- paper confessed, “and the absence of so much of what appeared in the edition of the ensuing year 1604, we hardly know what to infer.”

“To be, or not to be” in The Huntington’s Q1 Hamlet , 1603.

The writer of the report in the Literary Gazette expressed not only “gratification that an edition of Hamlet anterior to any hitherto known to the world has just been brought to light.” Like many other contemporary commenters on Q1, he also emphasized his “surprise that it should have been so long hidden,” for “it is a strange thing that such a volume … should have been suffered to be undiscovered or unnoticed among the lumber of any library.” He suggested that the book had been previously owned by Bunbury’s ancestor Thomas Hanmer, editor of the first Oxford Shakespeare (1743–44), although given Bunbury’s own, presumably more reliable, ideas about its provenance, the newspaper may have simply been associating it with Bunbury’s famous Shakespearean relative. If in fact Hanmer ever owned the volume, then he too had not understood its importance: had he known that it contained the sole exemplar of a remarkably different text of Hamlet, presumably he would have mentioned it in his edition. Like so much else about Q1, exactly how this book made its way into Bunbury’s closet remains a mystery. About its history prior to Payne and Foss’s 1825 reprint, we have only shadowy guesses.

“To be, or not to be” in The Huntington’s Q1 Hamlet , 1603.

The entire textual history of Hamlet is haunted by bibliographic ghosts. Repeatedly, new archival finds o.er tantalizing hints of texts that no longer exist, if they ever did, and of lineages that can no longer be traced. In the middle of the eighteenth century Richard Farmer found the earliest recorded mention of the play, Thomas Nashe’s satirical comment in 1589 that “English Seneca read by candlelight” helps unlearned dramatists patch together “whole Hamlets, I should say handfulls of tragical speaches.” Since no Hamlet playtext survives from the sixteenth century, and since Shakespeare had no known connection to the London theater in the 1580s, Nashe’s comment has engendered fierce debate over the dating of the play, its authorship, and Shakespeare’s biography ever since Farmer uncovered it. Farmer first drew attention as well to another allusion that poses similar chronological di¥culties, Thomas Lodge’s 1596 reference to a devil who “looks as pale as the Visard of the ghost which cried so miserally at the Theator, like an oister wife, Hamlet, reuenge.” Several early seventeenth-century writers also seem to allude to this phrase, which appears to have become famous, and yet it does not appear in any extant text of Hamlet.

Ophelia, with her brother Laertes beside her, madly laments the death of her father, Polonius, before Queen Gertrude and King Claudius. Prince of Denmark, Act IV, Scene V (engraving based on a painting by Benjamin West) from A collection of prints, from pictures painted for the purpose of illustrating the dramatic works of Shakespeare, by the artists of Great Britain, London: John and Josiah Boydell, 1805.

From the beginning of Hamlet, the time is out of joint, with the play strangely seeming to predate its own existence. Two decades after Farmer’s archival finds, Edmond Malone discovered the diary of Philip Henslowe in the Dulwich College Library as he was preparing his monumental variorum edition of 1790. The diary contained another ghost of Hamlet: “9 of June 1594, R[eceive]d at hamlet… viiij s.” Is this the Hamlet to which Nashe and Lodge refer? What is its connection to Shakespeare’s play? And how do these references relate to yet another Hamlet text that turned up in Germany in 1779? Published from a manuscript dated 1710 and possibly deriving from an early English troupe touring the Continent, this version of the play is entitled Der bestrafte Brudermord (Fratricide Punished). It bears some intriguing similarities to the Q1 text, particularly the name of the councillor, who is called Corambus. Unfortunately, the manuscript has since been lost, and so here again we stand at several removes from the “true original copy,” with little access to its textual history and provenance. Der bestrafte Brudermord is a strangely slapstick and farcical play; it has even been suggested that it is the script of a Punchinello- type puppet show. Partly for this reason, it was largely ignored before the discovery of Q1. It is remarkable how little commentary the German play generated in the decades after its initial publication; Malone, for instance, makes no mention of the text anywhere in his edition, nor does Isaac Reed in his editions (1803, 1813), nor James Boswell in his revision of Malone (1821). By the mid-nineteenth century, however, once scholars could see that it shared some odd features with Q1, Brudermord could no longer be so easily dismissed. Whereas these editors had remained completely silent about the German play, a century later entire books were devoted to its relationship to Q1.

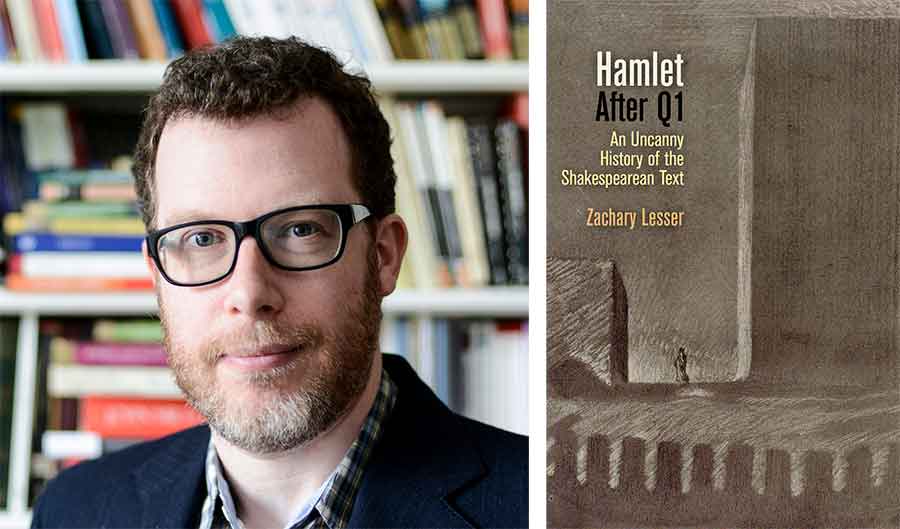

Left: Zachary Lesser, professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania. Photograph by Shira Yudko. Right: Cover of Hamlet After Q1: An Uncanny History of the Shakespearean Text (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015).

Together, these textual traces have conjured up the so-called Ur-Hamlet, a pre-Shakespearean drama that survives, if in fact it survives at all, only in the single phrase quoted by Lodge: “Hamlet, reuenge.” As Emma Smith remarks, despite the unfortunate detail of its nonexistence, the text of this “phantom play has been variously deduced, discussed and even edited by textual scholars,” fabricated from portions of Der bestrafte Brudermord and Q1. Again and again, we encounter missing texts, cryptic allusions, and bibliographic shades. Indeed, even Q1 existed as a faint echo before Bunbury found it: Malone noted that the second quarto (Q2) claimed on its title page to be “Newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much againe as it was, according to the true and perfect Coppie,” and he correctly inferred that “from [these] words it is manifest that a former less perfect copy had been issued from the press.”

Since the eighteenth century, then, the idea that there was a Hamlet before Hamlet has haunted Shakespearean editors and critics. If the play predated Shakespeare, just how Shakespearean was it? While we know that some kind of Hamlet play was being performed in London as early as 1589, we have very little idea of its content, despite frequent attempts to imagine it. What if this Ur-Hamlet looked more like Shakespeare’s Hamlet than we have generally been willing to admit? Shakespeare’s habit of drawing on narrative sources like Holinshed’s Chronicles and Cinthio’s Gli Hecatommothi was widely accepted, of course. And even Hamlet was acknowledged to have a direct prose source: The Hystorie of Hamblet, an English translation of François de Belleforest’s French translation of the Hamlet story in Saxo Grammaticus’s medieval Gesta Danorum. While the Hystorie did not appear until 1608 and is now generally understood to postdate the play, eighteenth-century scholarship imagined it as a primary source of Shakespeare’s version and inferred that there must have been an earlier, lost edition. The use of sources like these, however, did not pose the same threat to Shakespeare’s authority as the ghost of the earlier Hamlet play, since the Bard could easily be presented as spinning poetic gold from the dull straw of these bare prose accounts. Similarly, as we shall see in Chapter 1, many scholars believed that Shakespeare began his career by revising the dramas of other playwrights. But revising an earlier play of Henry VI was one thing; revising a previous Hamlet, Shakespeare’s masterpiece, posed far greater concerns. So long as there was no actual text that might be connected to an earlier version of the play, these doubts could be kept at bay, and eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century scholars largely agreed to forget about this pre-Shakespearean Hamlet after a routine mention of its existence. When Q1 reemerged from its purgatory in Barton Hall, however, all that changed. This “former less perfect copy” was far different from anything that Malone or anyone else had suspected, and it forced a reconfiguration of everything that had previously been known about the play.

As part of The Huntington’s Centennial Celebration, Zachary Lesser delivers the Ridge Lecture in Literature, “Hamlet and Other Ghost Stories,” in Rothenberg Hall at 7:30 p.m. on Nov. 13, 2019. At the same time on the following day, Nov. 14, Lesser will be joined on the Rothenberg stage by the Independent Shakespeare Co. for “President’s Series: Hamlet’s Bad Quarto,” which will include dramatic readings that compare scenes from Q1 with scenes from the more familiar version of Hamlet. Both events are free and require advance reservations.

Zachary Lesser is professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania.