Historical Markers

Posted on Thu., Oct. 17, 2019 by

Author Lynell George reflects on assembling the Huntington timeline

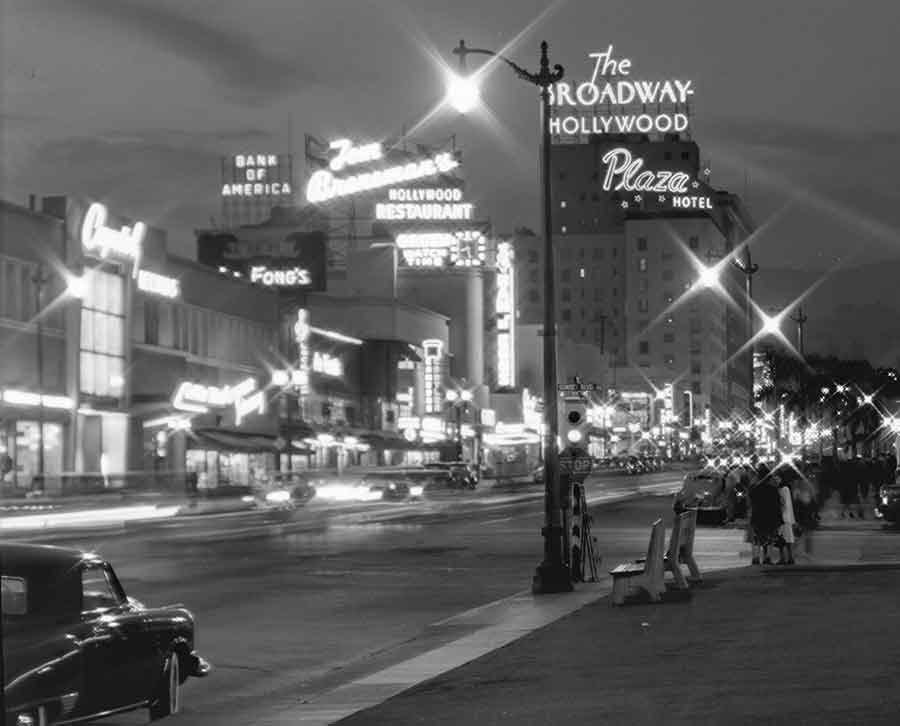

Vine Street at Sunset Boulevard, at Night, July 27, 1948. Photograph by Bob Plunkett. Ernest Marquez Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

As part of the preparation for The Huntington’s Centennial year, Los Angeles–based journalist and essayist Lynell George spent months delving into the history of the institution as well as the growing metropolitan area that surrounded it in an effort to produce an institutional timeline (now on view in the Mapel Orientation Gallery). She looked deeply at what drew many people, including Henry E. Huntington, to the West and how Los Angeles has prospered, fluctuated, and evolved in the past century. In a discussion with Frontiers Senior Editor and Writer Usha Lee McFarling, George discussed what she discovered about both The Huntington and Los Angeles during the project. The following conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Los Angeles–based journalist and essayist Lynell George in The Huntington’s Ahmanson Reading Room.

FRONTIERS: Tell us what you learned about what Los Angeles was like in Henry Huntington’s time in the early 20th century and how it evolved. What attracted him to the city, which was then still in its infancy?

GEORGE: What was interesting to me was to look at the way LA lit up in the imagination of the world. First, it was this place on the edge, and then, all of a sudden, it became a center and a destination that so many people wanted to reach. This started really early, and it took only a few decades for it to happen.

Huntington saw that early on. He saw that even though LA was far away from the East Coast, it was understood to be a paradise. He’s quoted as saying: “There is no limit to the possibilities of this favored section. Los Angeles cannot be kept down, it’s too good.” He predicted that people across all walks of life would come in droves and eventually create the largest city in the West and what he called, “one of the great centers of industrial energy in this country.” He was prescient.

FRONTIERS: Where was LA in its trajectory when Huntington first visited in 1892?

GEORGE: It was on its way, but it was still an outlier. It was still a place to be explored, and it still had space for people to self-create. LA was lighting up like a beacon, and for a lot of people, it was like a siren song. Henry Huntington was one of many people who heard that song. As he anticipated, the city drew people from every walk of life to try their luck.

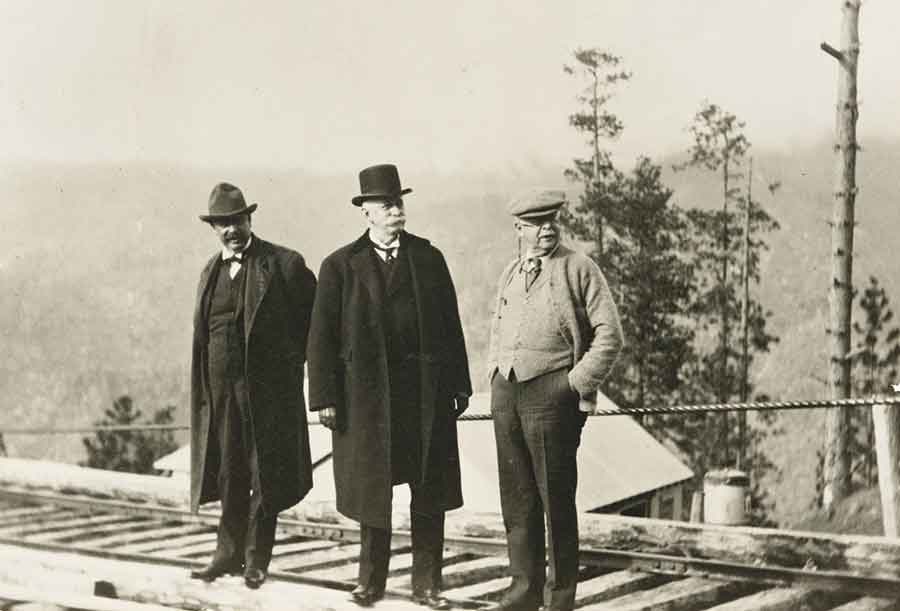

Henry E. Huntington (center) with Pacific Light and Power Colleagues at Big Creek, California, 1914. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

FRONTIERS: This is a city of so many stories. What did you learn as you sifted through some of them?

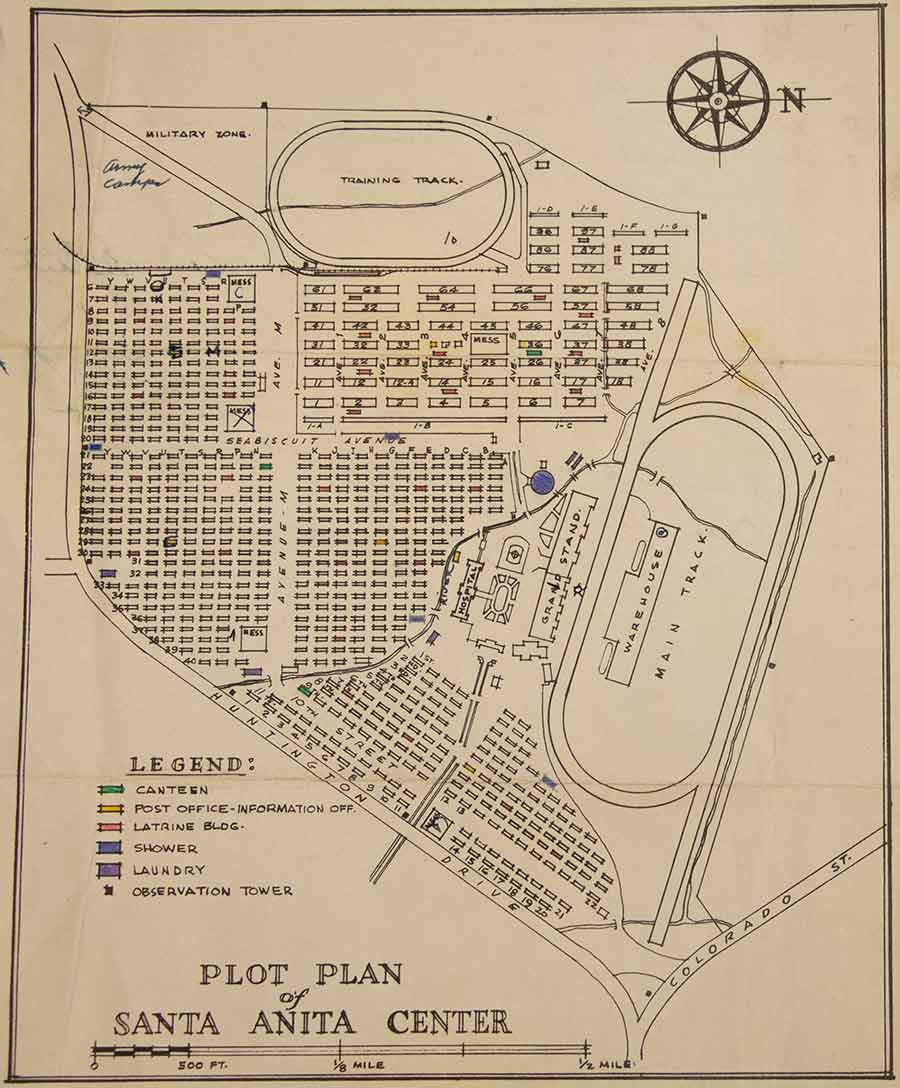

GEORGE: As it grew, LA became more than a destination. It became a dream, a goal, a place to make grand transformations. The city spread out, the skyline changed, and the population integrated, often in painful ways that put many dreams in conflict. The tension in the story is that there were so many people of different communities and ethnicities who tried to succeed here but hit walls while trying to set down their roots. For example, we have a history of racially restrictive housing covenants in LA that prevented people of certain races from buying houses in certain neighborhoods. And during World War II, there was an assembly center at the Santa Anita racetrack where Japanese Americans were housed temporarily before being transported to internment camps. So, you have the great wide open West, where some people are able to achieve their dreams and some people are deterred from achieving them. That was something that I wanted to examine. Here at The Huntington, there is a lot of documentation of such stories. The Huntington has the papers of Loren Miller, the Pasadena attorney who successfully argued the U.S. Supreme Court case that established the unconstitutionality of racially restrictive housing covenants. And The Huntington has numerous letters from Japanese American internment camps during World War II. Many documents that are part of The Huntington’s collections help tell these stories.

Plot plan of the Santa Anita Assembly Center, 1942, Arthur Ito papers. Assembly centers were created to house Japanese Americans temporarily until they could be transported to internment camps. The Santa Anita racetrack in California was one of the largest assembly centers in the nation, housing approximately 18,000 Japanese Americans. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

FRONTIERS: You spent time reading through decades of the institution’s annual reports. What did you learn from them?

GEORGE: I read about 80 years’ worth of annual reports. I was looking at how the trustees worked to carry forth Huntington’s vision after he died. What became of the library, the art collections, and the gardens? How were they cared for and shaped? There were many surprises. For example, they found bookworms in some of the books and had to figure out ways to eradicate them, so they partnered with University of California, Davis, to research the problem and wrote up their findings. During World War II, they had to find places to ship out some of the most important items in the collections because we were in a potential war zone.

I loved the language in the early reports. They really were sort of like letters to friends, very formal but very specific, about the challenges. It was a smaller institution then, so at that point, they were recording minor things that happened. For example, when they made the library public, it disrupted the work of the scholars, who were suddenly seated and conducting their research in public spaces, and so there were lots of apologies. I really did find myself lost in the spell of the period. I could see how everything in the institution got pieced together.

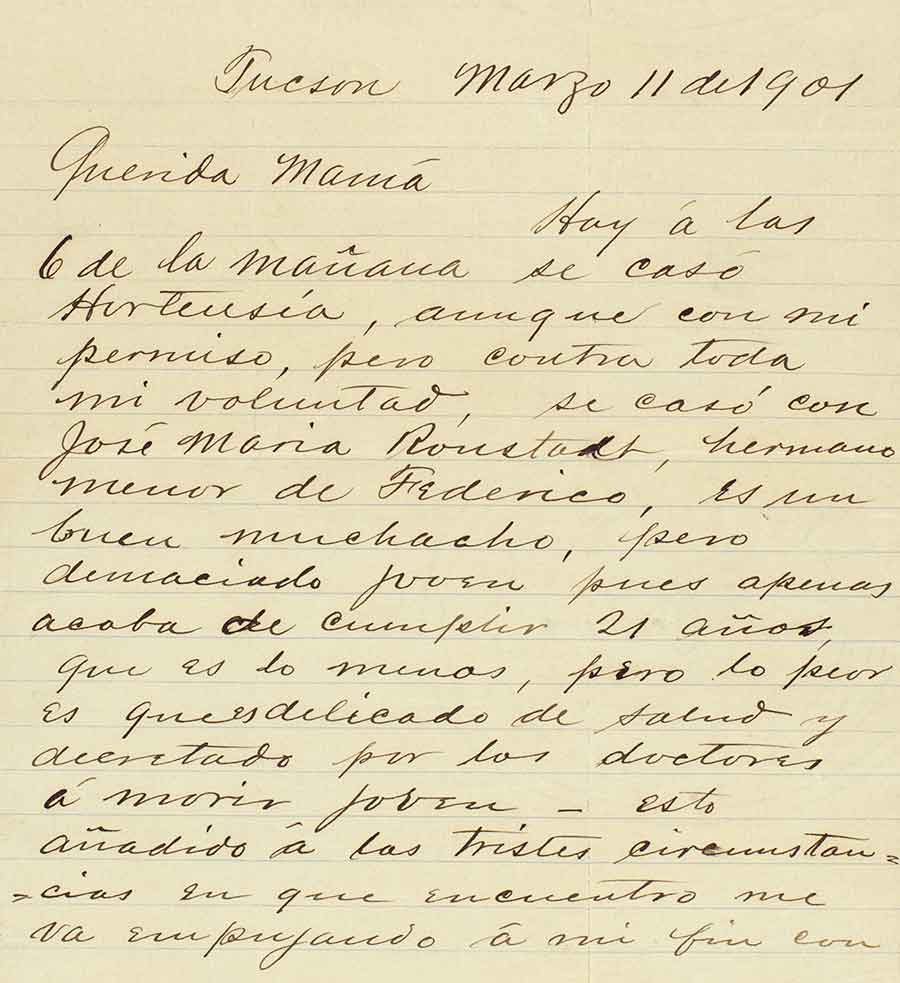

Letter, written in Spanish, from Winnall Augustín Dalton to his mother, María Guadalupe Zamarano de Dalton, March 11, 1901, regarding the marriage of his daughter, Hortense, to José Mariá Ronstadt—a man to whom the rock star Linda Rondstadt is related. Henry Dalton papers. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

FRONTIERS: The transition from private estate to public institution must have had challenges. What did you find?

GEORGE: It took a lot to convert this place from private to public; they worked at it for years and years. They had to figure out how to create a space that was safe and that scholars could use, as well as the general public. The trustees talked a lot about the general public and what they might need. They wanted the place to be accessible. They wanted to educate the general public, and this was very different from scholars who were coming here with very specific research agendas. They were trying to curate around the different groups.

FRONTIERS: Did you find anything in the annual reports that really surprised you?

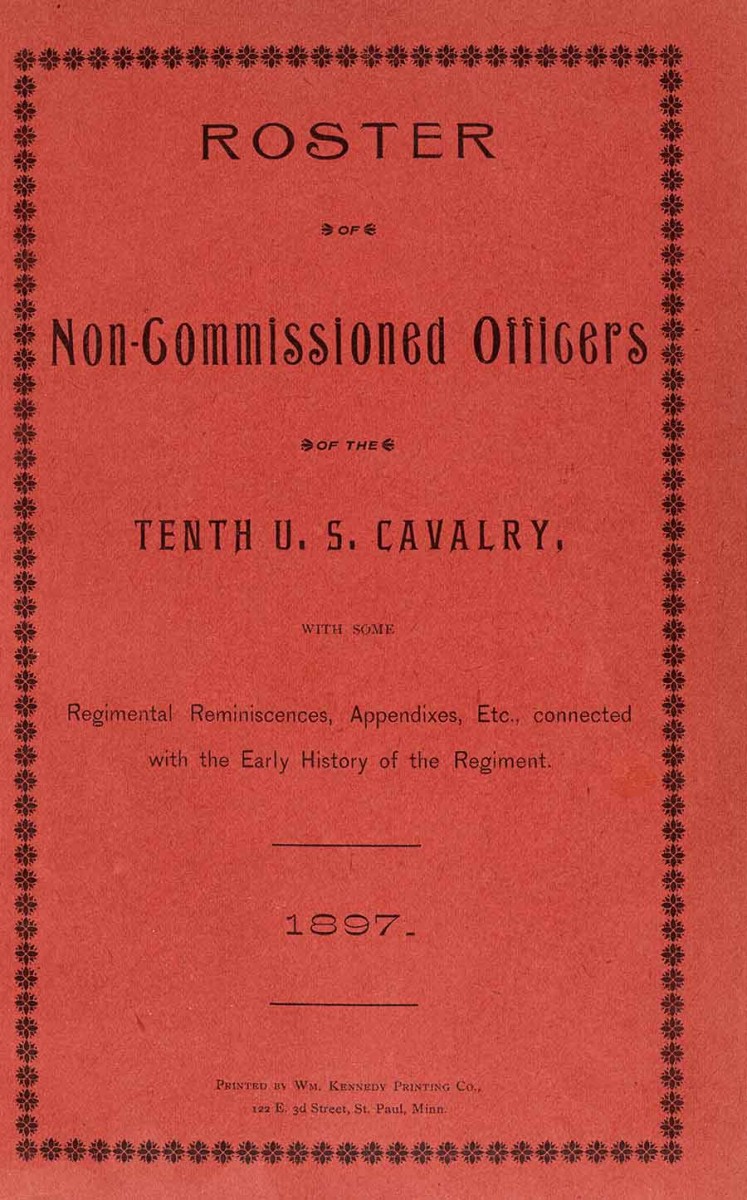

GEORGE: A professor of history named William H. Leckie of the University of Toledo came to The Huntington looking for letters written by African American U.S. Army soldiers in the 19th century, and he found a printed pamphlet containing reminiscences about African American cavalrymen. That was called out in the 1968 annual report: “To the scholar, these discoveries seem like near miracles. It is the frequency with which dreams can be fulfilled and near miracles occur that draws research scholars to this Library.” That was one of the first things I saw that specifically mentioned a scholar looking at the collection for African American voices and experiences.

Roster of Non-Commissioned Officers of the Tenth U.S. Cavalry, 1897. Printed by William Kennedy Printing Co. This pamphlet contains reminiscences about African American cavalrymen who served in the Tenth U.S. Cavalry. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

FRONTIERS: What are some of the ways you saw the institution responding to the LA area as it changed?

GEORGE: In the 1970s, The Huntington decided to allow people to enter the galleries barefoot. It was a really big deal. They went back and forth between concerns about cleanliness and this idea that they were an institution for the people. Hippie culture was a pervasive thing, and people were coming to The Huntington without their shoes on, so they decided to let them into the galleries as part of being more welcoming to a broader audience.

FRONTIERS: So, you saw the institution literally opening itself up to the city?

GEORGE: In the beginning, it was the more well-heeled residents of San Marino and Pasadena who were visiting. Also, conventions and special groups came from other cities and states to visit. You had to write in to get tickets, and you had to make appointments. You had to have a plan to get here, and that was a big deal. By the 1970s and 1980s, there was a real push to look outward, to hold special events for the public that were outdoor and informal, mini-talks where people could sit on the grass and use the indoor/outdoor space—that very classic Southern California lifestyle. There’s Shakespeare, there’s music. The photos are just great.

Loren Miller (1903–1967), Seated at Desk, ca. 1950. Unknown photographer. Loren Miller Collection. In 1948, Miller and Thurgood Marshall, who would later become the first African American Supreme Court justice, successfully argued Shelley vs. Kraemer, the U.S. Supreme Court case that established the unconstitutionality of racially restrictive housing covenants. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

FRONTIERS: What other changes and challenges did you discover?

GEORGE: By the late 1980s and early 1990s, LA was really becoming an arts center with so many different museums and performance venues. People were coming to LA in a way they hadn't before. Huntington leadership recognized this and knew they had competition. The Huntington used to be known as the “highbrow Disneyland,” and people would visit to take advantage of the gardens and the galleries, but now suddenly there were so many other options. So how was The Huntington going to be competitive? And then there was the 1984 Olympics and suddenly a clear need to have docents who spoke a variety of languages, as LA entered further onto the world stage and international tourism began to take hold.

Visitors at The Huntington, 1969, from The Huntington’s annual report for that year.

FRONTIERS: How did you see the collections changing over time?

GEORGE: There were major shifts and pivots. In 1963, the purchase of early English books was in decline because of the greatly limited availability of these items for sale. The leadership made a decision to change focus and strengthen the library’s holdings from continental Europe, emphasizing a program to acquire works of scores of European authors from the 15th through the 17th century. Shifting to collecting American art was another major pivot.

Over time, the curators began to secure collections, family archives, libraries, manuscripts, art, photographs, and letters that told a story of the history of this region.

FRONTIERS: What about the botanical collections? What stands out?

GEORGE: There were many interesting and unexpected events. For example, in 1951, when scientists from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Division of Plant Exploration were searching for plants that could produce cortisone, they asked for samples from The Huntington’s desert plant collection. The botanical division sent more than 2,000 pounds of agave leaves and other material. This was in keeping with Huntington’s vision that the garden would assist plant scientists and researchers in every way possible.

An Agave mapisaga ‘Lisa’ in The Huntington’s Desert Garden, 2019. In 1951, when scientists from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Division of Plant Exploration were searching for plants that could produce cortisone, The Huntington sent them more than 2,000 pounds of agave leaves and other material. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

FRONTIERS: What did you learn about timelines? Are they an effective way to tell the history of an institution or a city?

GEORGE: There are so many ways you can tell a story with a timeline. I came to realize, while doing my research, that time isn’t linear at all. People think of timelines as objective, but they really are subjective, depending on what you include. The challenge has been trying to decide what piece of the story to tell. I could have done 10 timelines with different sorts of histories.

Ultimately, the story became one of looking at how a place grows in our imaginations. I think about all the people who came west and all the things they held in their hearts. I think about what they wanted and how they thought the city might change them. That really becomes clear in many of the documents that live in the archives here.

What an essential repository this place has become. Anyone who is a historian or journalist trying to find new stories—when you think there are no new stories to tell—you just never know what is hiding in people’s libraries and their personal collections. This project really makes me want to delve in and read letters and study maps and look at photographs. There’s so much more to look at and explore.

Usha Lee McFarling is the senior writer and editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.