The Influential Vision of Carleton Watkins

Posted on Sat., June 22, 2019 by

His indelible photographs captured and promoted the American West

![Carleton E. Watkins [with cane, during aftermath of earthquake], April 18, 1906. Unknown photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.](/sites/default/files/frontiers/images/watkins_1.jpg)

Carleton E. Watkins [with cane, during aftermath of earthquake], April 18, 1906. Unknown photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In his new book, art writer Tyler Green argues that Carleton Watkins (1829–1916)—widely considered the greatest American photographer of the 19th century—was also one of the most influential artists of his era.

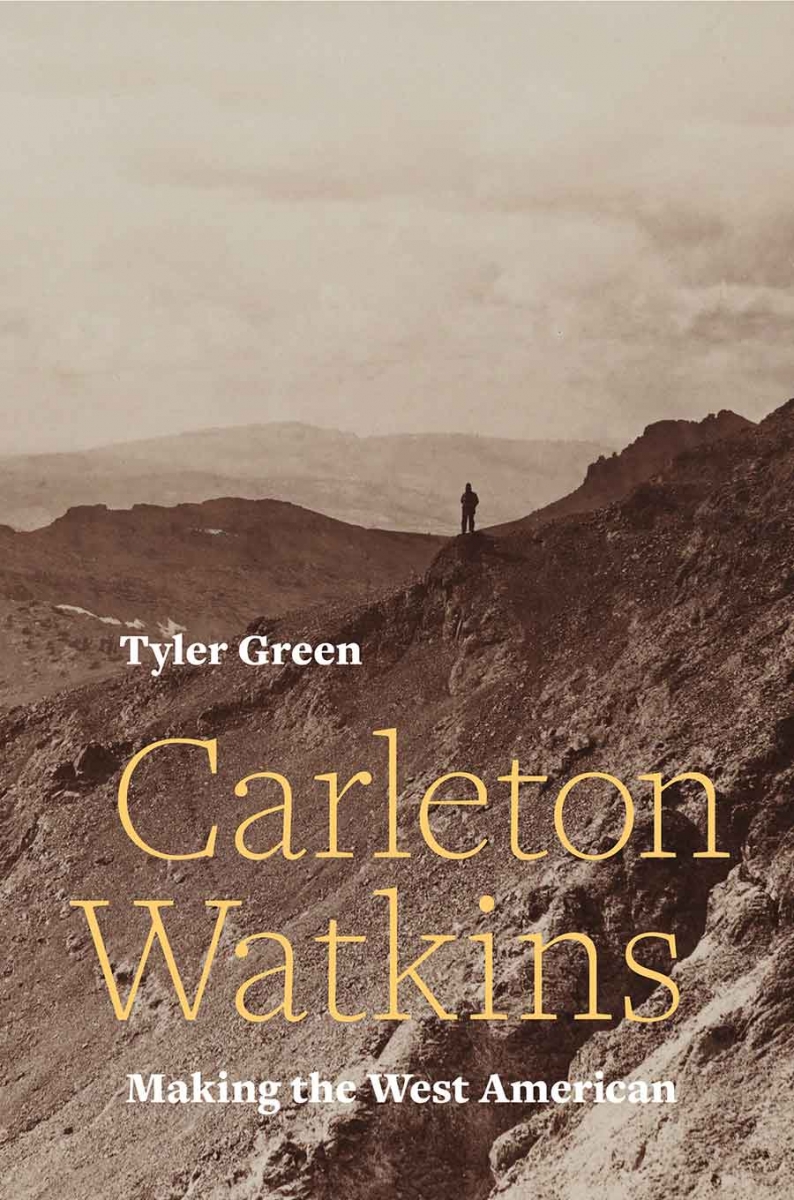

Carleton Watkins: Making the West American (University of California Press, 2018) is the first-ever biography of Watkins, as well as the first new history of the birth of the national park concept since 1948.

The Huntington owns more than 1,000 Watkins photographs. The collection’s origins can be traced to his boyhood friendships with members of the Huntington family. At the center of The Huntington’s holdings are four albums of Watkins’s mammoth (18 x 22 in.) views bound in morocco leather. Over the years, The Huntington continued to add to its Watkins holdings through gift and purchase, making it one of the great repositories of his work. The following is an excerpt from the introduction to Green’s book, winner of the 2018 California Book Awards's Gold Medal for Contribution to Publishing. (The excerpt is reproduced with permission by University of California Press).

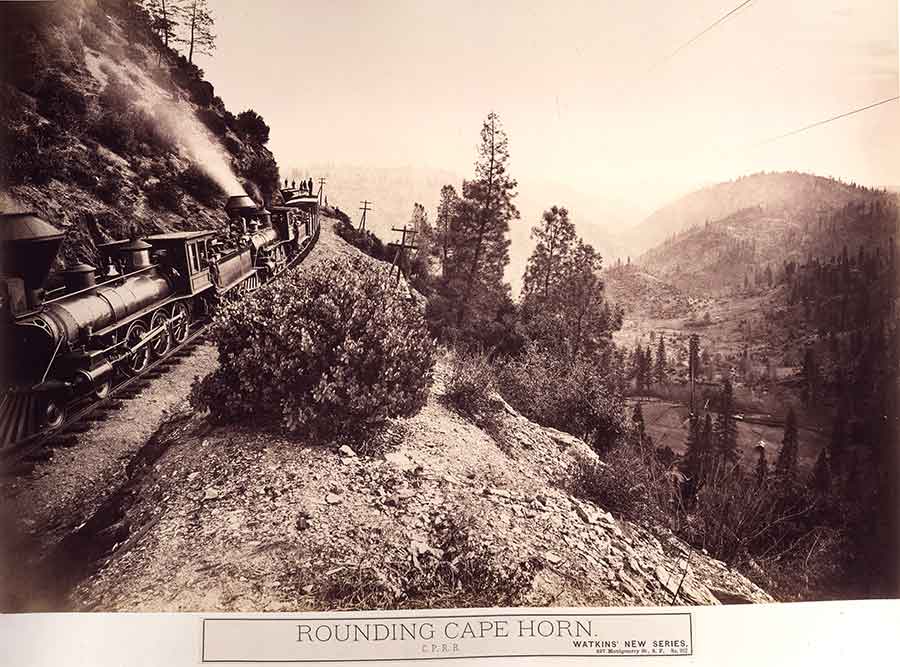

Carleton Watkins, Rounding Cape Horn, Central Pacific Railroad, Placer County, California, ca. 1876. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

San Franciscans have always heard earthquakes before they have felt them. Just after dawn on the morning of April 18, 1906, 76-year-old Carleton Watkins, like nearly everyone else in San Francisco, heard a mighty rumble.

It started as a low hum southwest of the city, under the Pacific Ocean. The sound traveled through the seabed until it reached the western edge of the city, Ocean Beach, and continued under the rocky highland that was the mostly unpopulated west half of San Francisco, underneath the Army Presidio and nearby Golden Gate Park, under Twin Peaks, then right down the rail line that linked the park to the city. As it hit the Western Addition, where the populated core of San Francisco began, it grew into a wall of sound. Until now, the deep roar was made by the earth acting on itself, by rock grinding against rock. Now it was also timbers snapping, from bending, and brick walls crashing. This was when the invisible disaster in the making would have awakened Watkins, one of the few San Franciscans who had lived through the last great earthquake in 1868, a temblor that left streets with deep, broad cracks and that knocked buildings to the ground. Once you hear a big earthquake, you never forget.

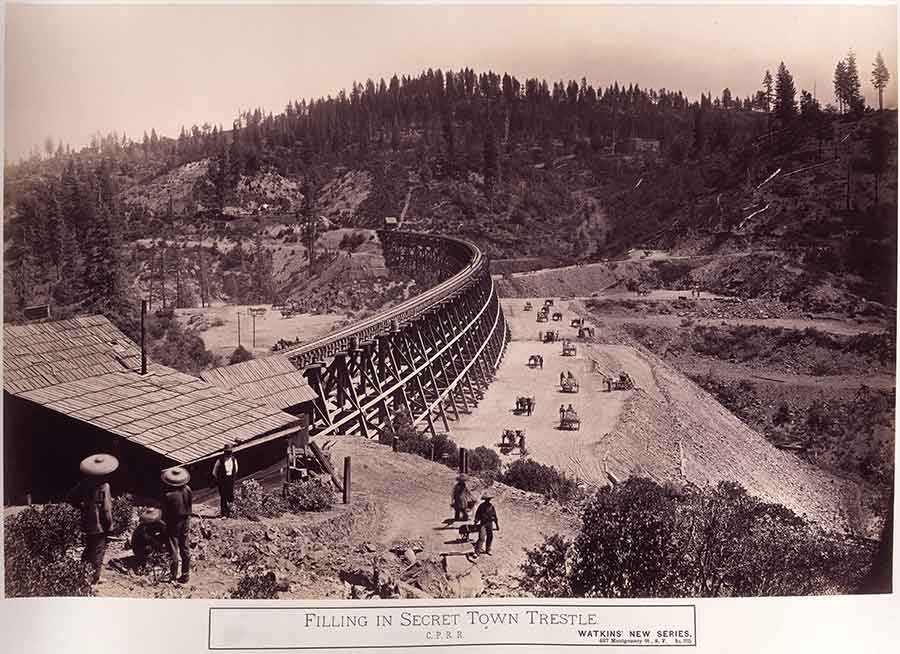

Carleton Watkins, The Secret Town Trestle, Central Pacific Railroad, Placer County, California, ca. 1876. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

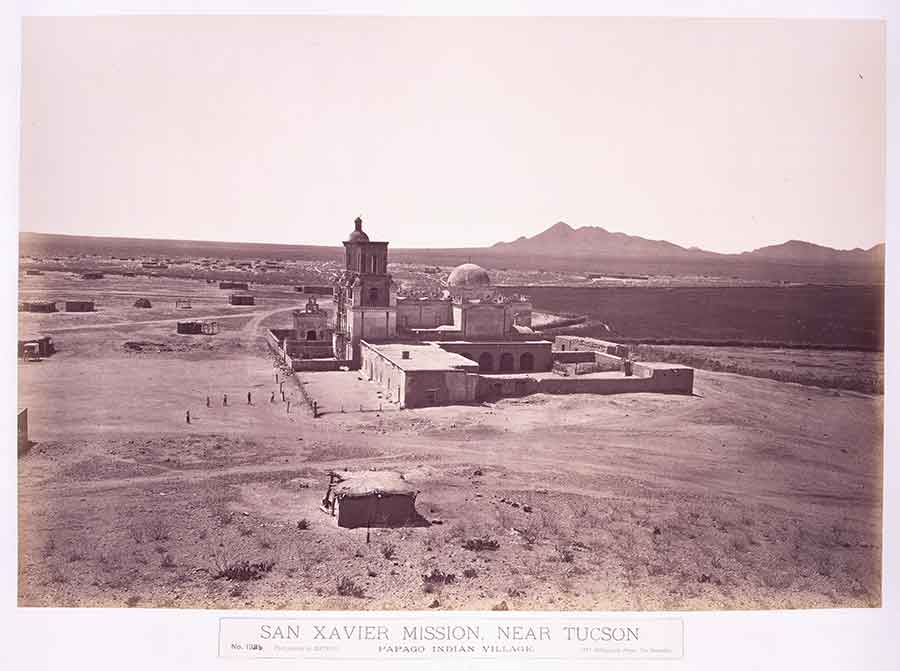

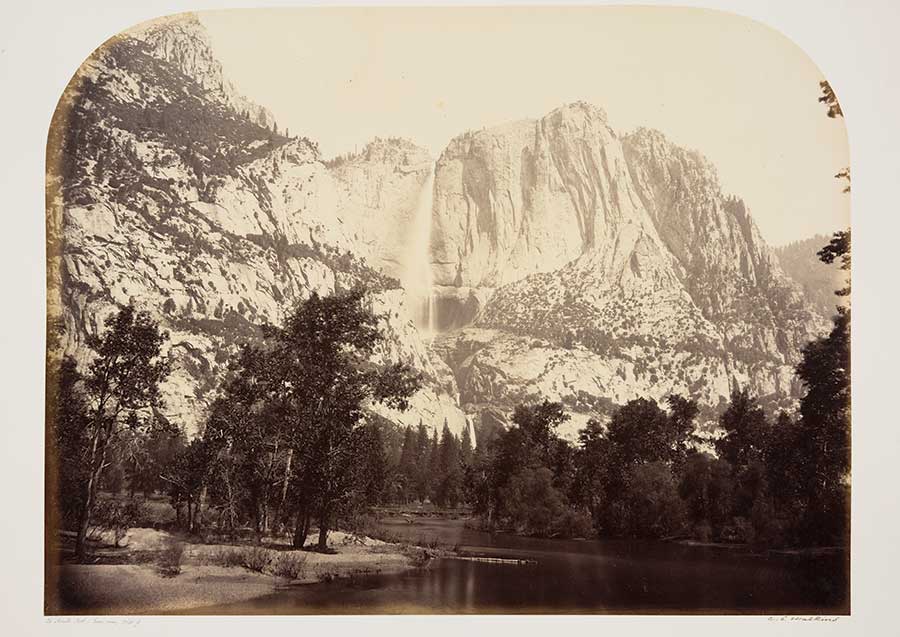

Back in 1868, Watkins, then a sprightly 38-year- old, had grabbed a couple of cameras and headed out into the streets. Back then, he was at the height of his powers. He was famous not just in San Francisco but in New York, Boston, Washington, and even in Europe, where he had just won a medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair. In that exciting decade, Watkins’s pictures of Yosemite Valley, created in the spirit of strengthening ties between California and the Union, exhibited in New York and passed around Capitol Hill and probably the White House, created a sensation and motivated Congress and President Abraham Lincoln to preserve a landscape for the public, the first expression of the idea that would later come to be known as the national park and that would lead to the designation of public land such as national forests. His reputation made, Watkins spent the next two decades making pictures of the West that defined the region for scientists, businessmen, bankers, policy makers, his fellow artists, and Americans who were thinking of moving west.

Watkins’s customers, clients, and friends were men who pushed America into an age gilded by the gold they extracted from the mountains of California and Nevada. These bankers, miners, and land barons collected Watkins’s work and hired him for commissions that both showed off their wealth and would help make them wealthier. Among Watkins’s collectors and sometime commissioners were John C. Frémont, conqueror of Indian tribes, explorer, railroad promoter, brother-in-law of one of the Senate’s most powerful, West-focused men, and the first Republican presidential candidate; John’s wife, Jessie, the brains behind Frémont’s books, his 1856 presidential campaign, and his California gold mine; and scientists such as John Muir, Clarence King, and George Davidson. Easterners such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Frederick Law Olmsted, and Asa Gray, the most important scientist of the 19th century, who would bring Darwin’s revolution to the United States, snapped up Watkins’s too. The U.S. Senate hung pictures by Watkins in the Capitol, and an outgoing American president may have wanted to own four Watkinses so badly that he stole them from the White House.

Carleton Watkins, Mission San Xavier del Bac, near Tucson, Arizona Territory, 1880. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Watkins courted men of learning and influence, but he made surest to become close with men of capital. First through John and Jessie Benton Frémont and later through William C. Ralston, the most powerful investor and banker in the West, then through the executives of San Francisco water, railroad, and mining companies, and then through land baron and mine owner James Ben Ali Haggin and his colleagues who made the desert bloom, Watkins built business connections to California’s wealthy elite, to the miners who extracted gold, silver, and copper from western lands, to the ranchers who raised cattle and later engineered the land into suitability for staple crops and orchards, and to the banker who helped enable it all. Watkins was accepted as one of them: he was an early member of San Francisco’s famed Bohemian Club, the private enclave of San Francisco’s journalists and its moneyed, progressive elite. But in 1906, Watkins was poor, as he had been for over 10 years. The skills that had brought him to prominence were gone. Photography was no longer a specialized skill; it had been a full decade since technology had advanced and passed Watkins by. Now Watkins was an avatar of a West in which allied men of capital and their companies controlled vast wealth and power, and in which the unaffiliated individualist, no matter how great he had been at what he did, withered.

Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Falls (Lower View) 2630 ft., 1861. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Now, as the sound of the earthquake built into cacophony, Watkins was no longer famous or wealthy. His home was apparently a cheap apartment in a low-rent neighborhood south of the Slot, as San Francisco’s Market Street was then known. Except for a handful of photographers and photography aficionados who recognized his work as important to the West and to America, he had been forgotten.

Below the Slot, apartment buildings were stacked close, and the walls were thin. When the roar was followed by shaking, Watkins would have heard the iron stoves commonly used for heating crashing through his and his neighbors’ floors. He’d have heard plaster separating from walls and ceilings, bricks crunching and disintegrating as the timbers and giant iron beams that held up all of it snapped. A few blocks away, the dome on top of San Francisco’s brand-new City Hall smashed through three floors of offices. In his own rooms, Watkins would have heard the sound of many hundreds of his glass negatives clanging back and forth. Within moments, nature’s low rumble was replaced by the sound of man’s ruin, as an untold number of apartment buildings, boardinghouses, industrial buildings, meatpacking factories, hotels, office buildings, banks, theaters, and more crashed to the ground.

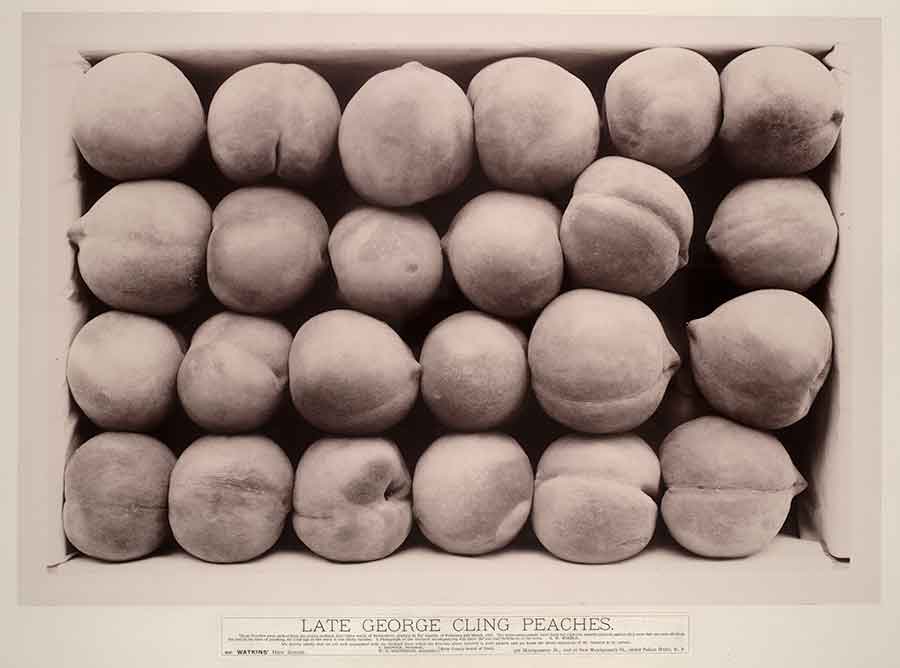

Carleton Watkins, Late George Cling Peaches, 1888–89. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The earthquake lasted 45 seconds, but the disaster was only just beginning. Even as buildings continued to fall, Watkins would have smelled smoke. Fires, ignited by all those hot stoves crashing through wooden floors, started throughout the city. To this day, no one knows how many fires started in the minutes after the earthquake. Many grew into infernos that consumed entire blocks, entire neighborhoods, and within hours, much of the city itself.

By now Watkins’s senses would have been overwhelmed: he heard disaster, he felt the vibrations of falling buildings, and every minute the smell of fire intensified. The more smoke Watkins smelled, the more afraid he must have been. For weeks, Watkins had been preparing to transfer much of his life’s work to the museum at nearby Stanford University. In fact, just a week before the earthquake, a curator from the university had visited Watkins in these very rooms in preparation for the university’s apparent acquisition of Watkins’s archives, the first time an American university or museum would recognize a photographer’s importance in such a way. We don’t know if Watkins thought about any of that. There may not have been time. Watkins rose and dressed in a black suit, put on his hat, and grabbed his cane. He left his negatives, prints, and papers behind—what else could he do?—and left his house.

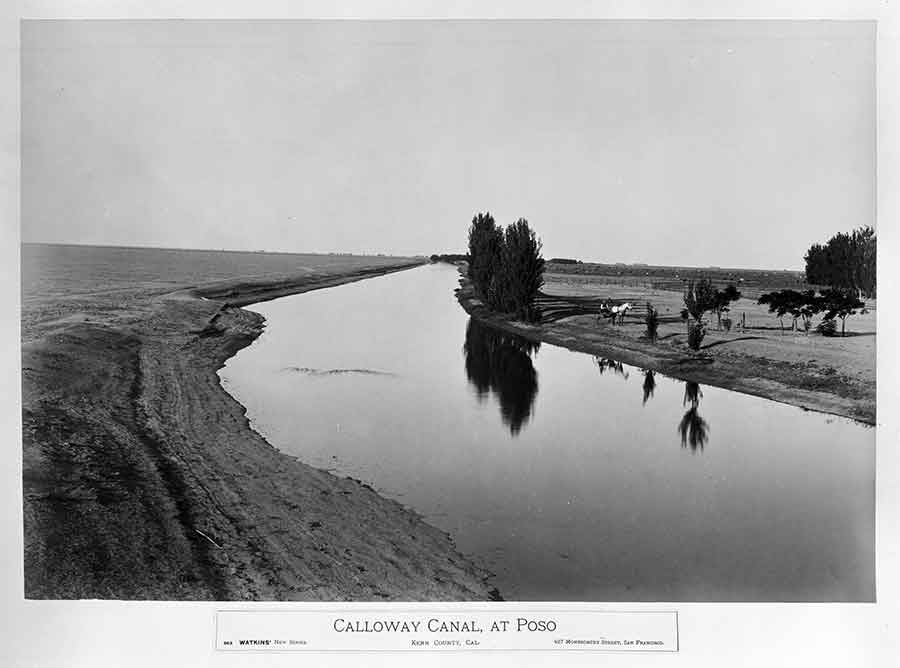

Carleton Watkins, View on the Calloway Canal, near Poso Creek, Kern County, California, ca. 1887–88. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

A photograph captures what happened next. Gingerly, Watkins walks along a sidewalk toward Russian Hill or Nob Hill, toward somewhat safer ground. Bricks that had fallen off the front of the building to Watkins’s right litter the sidewalk. A few feet in front of him, the crumbled front of another building covers the street. There are flames in the windows of the Beaux-Arts building behind Watkins. Thick black smoke streams from its roof.

Watkins pushes much of his weight onto the right side of his body, which is further transferring it to his cane. He is having difficulty walking. A younger man keeps a steadying hand of Watkins’s back. Nearly everyone in the picture is gawking at the fires, at the damage. Everyone, that is, except for Watkins, who stares blankly ahead. Someone standing behind a camera has yelled something like “Look here!,” and so Watkins, a man who had once been famous for seeing creatively, looked where he was told. He might as well; while he could smell the ash and smoke, while he could feel dust coming down like snowflakes, while he could feel the sidewalk shake, he could not see. The greatest photographer and most influential American artist of the 19th century was now nearly blind.

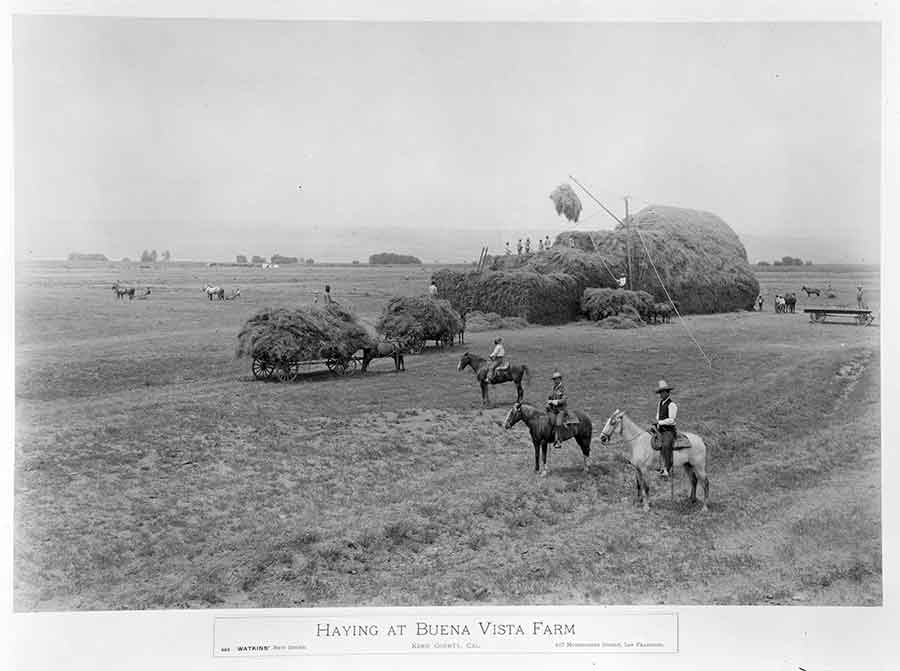

Carleton Watkins, Haying at Buena Vista Farm, ca. 1886–89. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As someone led Watkins away from the Slot in the hours after the quake, Watkins would have known that everything he had—all the photographs he’d taken since 1876 plus a life’s worth of records, correspondence, notes, and more—was in danger. Within hours a fire would destroy all of it. The Carleton Watkins collection would never make it to Stanford University, where an institution’s early recognition of a “mere photographer” as a major figure of post–Civil War America may have played a pioneering role in elevating both Watkins as an artist and photography as an important art historical discipline nearly a hundred years earlier than it did.

As a result of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, which destroyed not only all of Watkins’s possessions but also much other material around the city that might have informed our knowledge of the 19th-century West, almost no textual documentation of Watkins’s life exists. Among the first-person accounts of Watkins’s life that have survived are a couple dozen letters in the artist’s own hand, two flawed and routinely factually incorrect oral histories provided by Watkins’s daughter, Julia, and a similarly error-strewn mini-biography by one of California’s first historians, a Watkins friend named Charles Beebe Turrill.

Tyler Green’s Carleton Watkins: Making the West American, University of California Press, 2018.

Telling the story of Watkins and his impact on the West and the nation has required building an understanding of his community, the people with whom he interacted and for whom he worked, understanding that constellation, and then intuiting how Watkins and his work fit into it. Fortunately, many of the people with whom Watkins interacted during his life left California for the East, either to return home or to work there. Many of the most important archives related to Watkins and his work are in places such as Massachusetts, Vermont, and Washington, D.C., places where earthquakes and fires were less common.

Thank goodness for Watkins’s pictures, which are both art and historical documents. Watkins was a preposterously prolific artist. He made over 1,300 mammoth-plate pictures, the huge photographs on which his reputation rests today, and thousands more stereographs and smaller-format pictures. They provide the most important clues to his story, to the men and businesses for whom he worked, to the ideas and artworks that informed his approach to art, and to the 19th-century world to which he hoped to contribute.

Writing about Watkins has been like writing about artists such as Goya or Titian, other artists about whom little textual material survives. Like the historians who have written about them, I have done my best to reconstruct and understand Watkins’s world. The biographer T. J. Stiles has written that we read (and write) biography to affirm our belief that “the individual matters… How does the world shape the individual, and the individual the world? To what extent are convictions, judgment, and personality merely typical, embedded in a larger context—and where does the individual wiggle free?” Surviving material does not allow us to know about Watkins’s personality, his convictions, his judgment, or much of anything else about him. However, through his work and its impact, we can see how important his individual life was to art, to the West, and to America. That’s all any of us will be able to do.

Tyler Green is the producer and host of The Modern Art Notes Podcast and was previously the editor of the website Modern Art Notes, which published from 2001 to 2014.