Mapping a City on the Move

Posted on Thu., June 20, 2019 by

Pioneer cartographer Laura L. Whitlock captured a megalopolis in the making

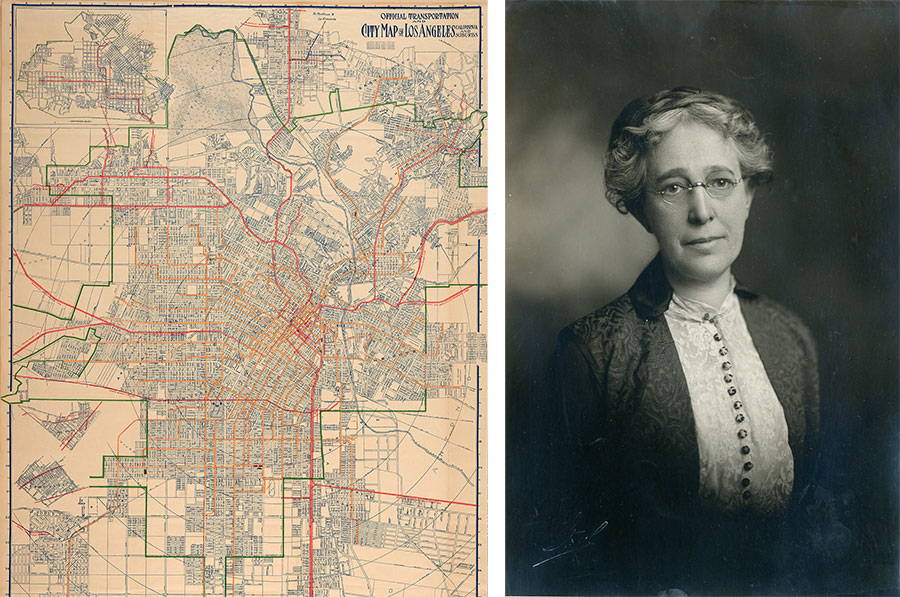

Left: Detail of Official Transportation and City Map of Los Angeles, 1919. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Laura L. Whitlock. Unknown date and photographer. Security Pacific National Bank Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

In August 1919, Henry and Arabella Huntington drafted documents converting their San Marino ranch into a “library, art gallery, museum, and park.” Today, staff across The Huntington, including myself, are working on a host of exhibitions and programs that, from fall 2019 to fall 2020, will celebrate and reflect on the past 100 years, while highlighting the ideas that may shape the next century.

For my part, I have been happily immersed in helping to prepare “Nineteen Nineteen,” a major exhibition that will examine the institution and its founding through the prism of a single, tumultuous year. It displays more than 250 objects drawn exclusively from The Huntington’s collection of manuscripts, photographs, books, and art. A collaboration of James Glisson, interim chief curator of American art, and Jennifer A. Watts, curator of photography and visual culture, the exhibition will be on view from Sept. 21, 2019, to Jan. 20, 2020, in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery.

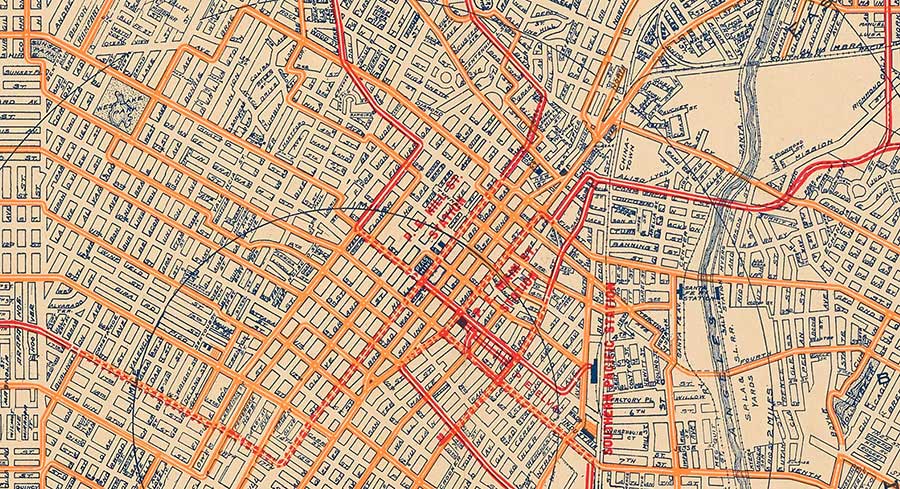

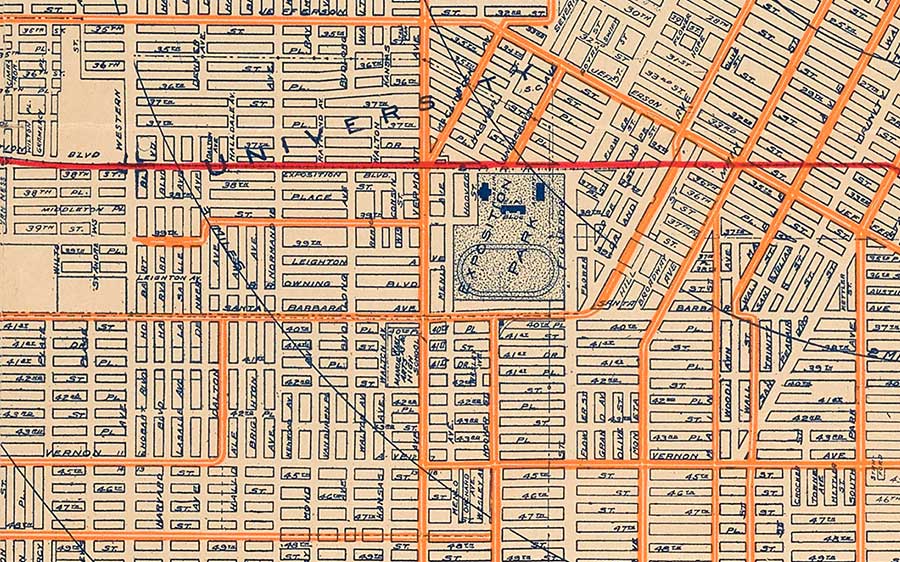

All rail lines lead to downtown Los Angeles, in 1919. Whitlock’s tracings measure radial distance from this core district—appearing to give it a pulse.

Something I love about the show is the diversity of its contents, all connected to its namesake year. Those who want to see resplendent manuscripts, the works of famous artists, or the journals of great (or notorious) individuals will not be disappointed. Everyday objects—such as posters, sheet music, and a pen knife—also tell stories. These are just as intriguing as those behind rare first editions or fine works of art.

The Official Transportation and City Map of Los Angeles, one of numerous maps featured in the exhibition (spoiler alert: maps were very significant nationally and internationally in 1919), is proof of this. Its creator, Laura L. Whitlock, was the first woman cartographer in the United States to publish her work for the mass market and the first person in the country to win a federal lawsuit establishing copyright protection for future mapmakers. Her map’s form and content reveal not just infrastructure to come (the 405 Freeway, for example), or defunct neighborhood names (like “Eagle Rock Valley”), but also her own personality and feelings about Los Angeles and its once-extensive streetcar systems.

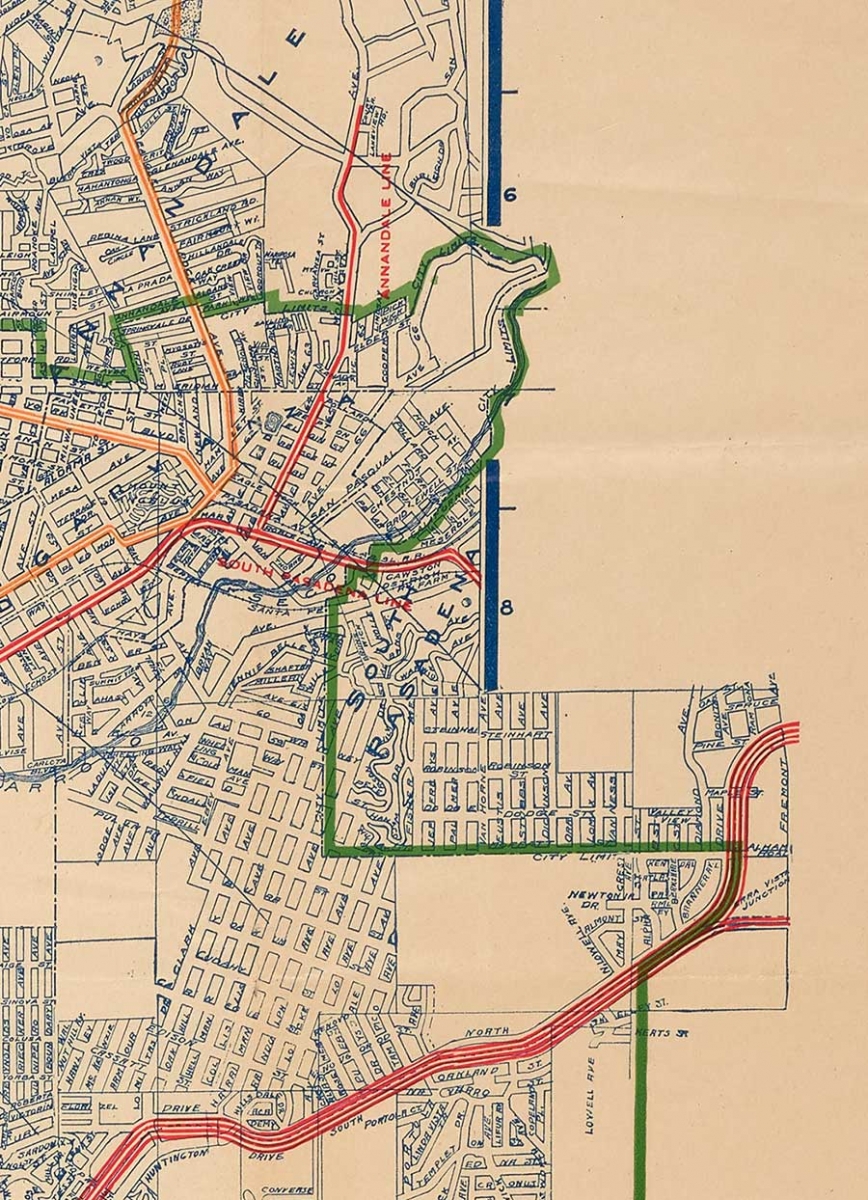

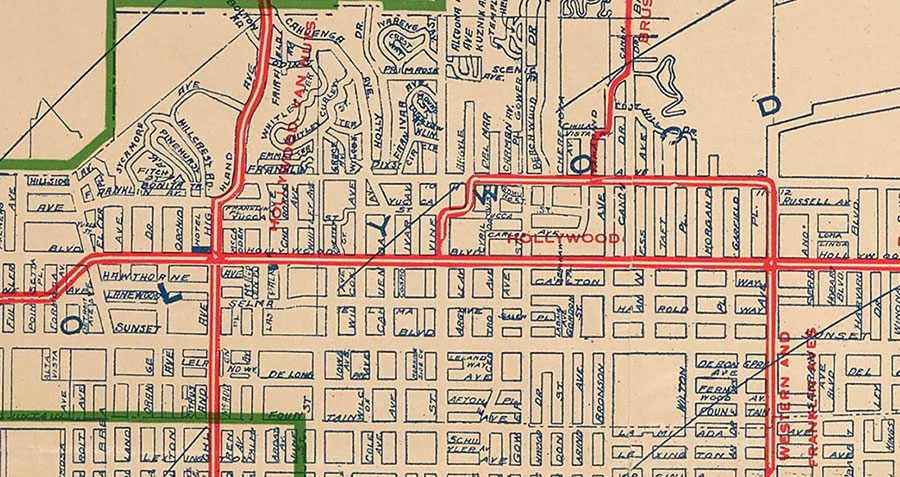

The top-right corner of the map shows the coordinate system Whitlock included for viewers to find and describe locations. Not only do the neighborhoods of Garvanza, South Pasadena, and El Sereno exceed the green line of the official city limits—they punch through the frame of the map itself!

Whitlock was born in Iowa in 1862 and began her professional life as a music instructor. In 1895, she moved with her mother to Los Angeles, where numerous entrepreneurs (including Henry E.Huntington) had been laying track since 1873. By the time of her arrival, the county was on the cusp of claiming one of the most robust rail networks in the nation. Its population increased by 450 percent from 1900 to 1919. For Whitlock, trains and the mobility they allowed proved to be more than a convenience of her new home—they changed the trajectory of her career. She initially continued teaching music while moonlighting in a florist’s shop. Her name soon appeared in the newspaper as she offered guided group excursions to the orchards of Riverside and Redlands, the beaches of San Diego, and the Grand Canyon.

By 1903, Whitlock opened her own “tourist headquarters” downtown. An announcement in the Los Angeles Times referred to the midwesterner as “one of the most competent instructors on the glories of California.” The newspaper stated that the space had “no commercial features” but merely “lounging furniture and other paraphernalia designed for…travelers seeking information.” Advertisements placed in the paper by Whitlock promote a “Travel and Hotel Bureau” run by “L. L. Whitlock, Agent for all transportation lines. Leading hotels. Resorts of California. Hawaii.”

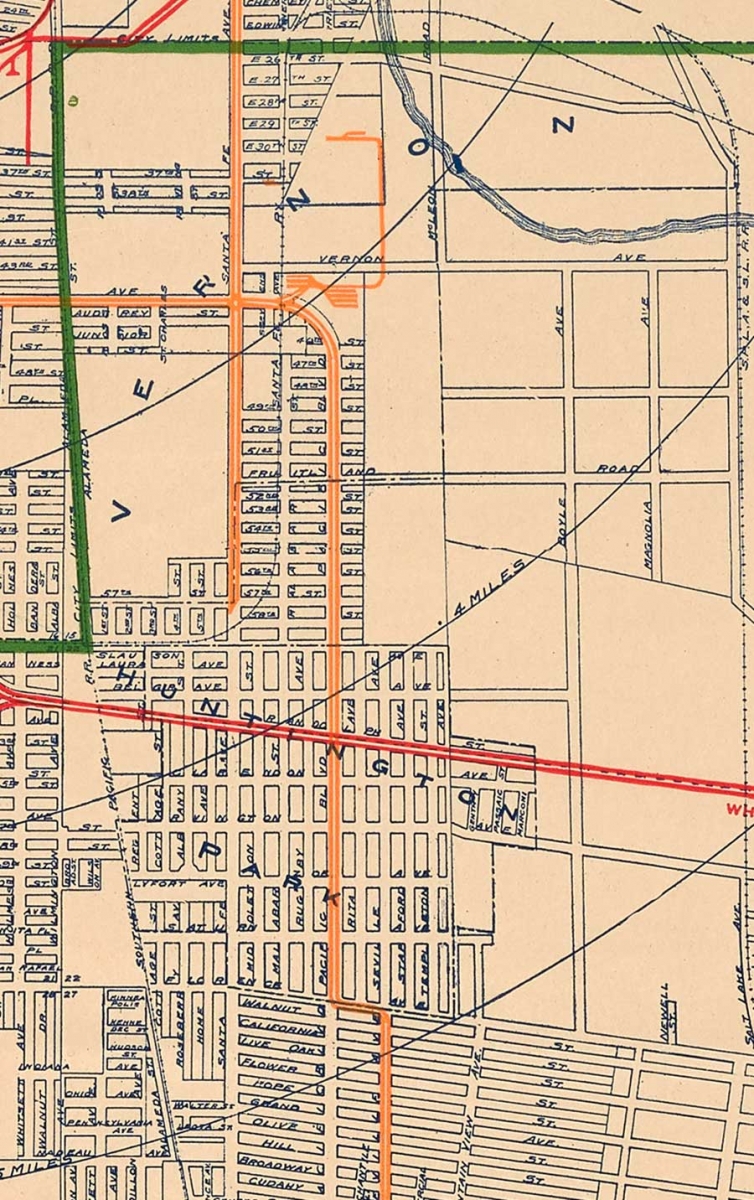

The cities of Vernon and Huntington Park were also key parts of the greater L.A. area that Whitlock included in her map, despite technically existing beyond the green city-limit line. In this less-dense corner of the plan, we can see the distances from downtown Los Angeles on Whitlock’s one-mile radial rings.

At some point while running her agency, which the Times characterized as recreational, Whitlock took up cartography. Like commerce, mapmaking was not considered the purview of women at the time. Though a handful of women throughout history had pursued the profession, they did so predominantly under the aegis of an existing family business. It was not until World War I, and to a larger extent World War II, that women were sought for cartographic work. Even then, like their “computer” counterparts in science and technology, they worked as subprofessionals with little hope of promotion.

It is not clear what sparked Whitlock’s interest in mapmaking. Perhaps she was tired of doling out directions to confused tourists at her headquarters. But like every new venture she undertook, she had a flare for it. The Huntington map, for example, was first printed in 1910, and on its sixth edition by 1919. In drafting it, Whitlock must have leveraged her years of working closely with railroad personnel while she guided tours and booked vacations. In a 1911 Times advertisement, Whitlock claimed that hers was “the only map containing exclusive railway data, as the electric railway officers give no data to other publishers.” By 1918, Sunset magazine referred to her as “the official map-maker of Los Angeles county.”

To say Whitlock was obsessed with detail is an understatement. Exposition Park is a small square on her map, yet she still locates the Natural History Museum, Expo Bloc, Armory, and the racetrack-turned-rose-garden within it.

Popularity can be a curse as well as a blessing. The Official Transportation and City Map was so successful that 20,000 pirated copies were sold around the city. The perpetrators included a Mr. Bowditch Blunt (the man who printed the duplicates) and a more formidable foe, the Los Angeles Map and Address Company, which published and sold the stolen plan. Whitlock may have included a “copyright trap”—a purposeful mistake or artifact inserted into a map by its maker to catch plagiarizers. In any event, Blunt’s version was so similar to the original that a lawyer advised Whitlock to file a civil suit for damages immediately.

Whitlock was aware of the potential landmark status of her case. Rather than agreeing to a settlement in a local court, she dug in for a protracted battle in the federal arena. Though the first U.S. copyright law dates back to 1790, it had never been applied to maps specifically. Whitlock fought for three years, through three levels of court, undergoing intense cross-examination. She reinvented herself once more, this time as an expert in copyright law. When she finally walked away victorious, she had won $20,000 for herself and set a precedent that protected the intellectual property of future cartographers. Many cartographers from all over the country requested the court transcripts.

In the thick of Whitlock’s map, beneath the word “Elysian,” we get a valuable glimpse of the layout of Chavez Ravine, the neighborhood that existed before the valley was forcibly wrested from its Chicano owners to build Dodger Stadium in the 1950s.

Maps for public consumption are assumed to visually represent geographic and statistical truth. In reality, their makers leave behind traces of themselves and their attitudes toward what is depicted, like so many copyright traps. This may be difficult to see at first in Whitlock’s map because of its meticulous detail. Like an anatomical model, she depicted Los Angeles in layers, starting with its rivers and green spaces, topped by its streets, then topped again by its rail network. Yet despite the visual density, the train lines are the clear focus. Colored in red and yellow, they are like arteries carrying blood that feeds the city tissue, rendered in dark blue. Train lines also were personally nurturing for Whitlock, bearing her from Iowa to California and furnishing her livelihood and personal pleasure as she explored the Pacific coast and Southwest alongside her clients.

The feature that stands out most on the map, after the red-and-yellow rail systems, is the angular green line designating the official limits of Los Angeles. It seems to have been drawn less to emphasize boundaries and more to demonstrate how the city ignores and exceeds them. This sense of accelerating expansion is bolstered by the circular tracings that emerge from downtown like rings on a pond. Noticeable in other turn-of-the-century maps, their practical purpose is to designate radial distance, in this case, from city center. However, Whitlock extended her circles all the way to the map’s edge, as if her Los Angeles not only has a pulse, but is alive and kicking. Or perhaps they’re not separate rings but one giant train wheel, whooshing by. In any case, the design further underscores a link between transit and the current and future geographic and financial growth of the metropolis.

As Whitlock’s map shows, the names Sunset Boulevard and Hollywood have always been intertwined.

A final hint that Whitlock’s map was made not just to explain Los Angeles and its streetcars, but to celebrate them, is its size. At four feet high and three feet wide, it is not convenient for on-the-go navigation—even by 1919 standards. Its true purpose was likely proud display, a hypothesis additionally supported by the Los Angeles Map and Address Company, which, the Times reported, made “wall maps” with its unauthorized copy. What is more, every city street is named both on the map and in the index that occupies the bottom and right sides of the plan. Whitlock’s map, though certainly useful for wayfinding, gave Angelenos the added thrill of finding their home amidst the complexity—inviting them to visualize themselves as part of the city’s dynamic growth and prosperity.

For many people, this invitation to abundance rang false. As Henry Huntington’s own business model demonstrates, streetcar expansion went hand in hand with mass real estate buyouts. These buyouts displaced ethnic minorities and the economically disadvantaged already living on the land. These same individuals were also barred, financially and/ or socially, from returning to their old neighborhoods, newly outfitted with middle-class housing and the added attraction of rail connectivity. Thus, while Whitlock and her map are triumphant and inspiring, they tell only a fraction of the story of the year 1919, a narrative that even the most comprehensive exhibition could never relate in full.

Lily Allen, a curatorial assistant at The Huntington, has contributed entries on five items (including Whitlock’s map) featured in the upcoming catalog for the “Nineteen Nineteen” exhibition. She is grateful to Glen Creason, librarian of history and genealogy at the Los Angeles Public Library, for sharing the photograph of Whitlock, and for his discussion of Whitlock’s work in his book Los Angeles in Maps (2010).