Painting the Wind

Posted on Wed., June 19, 2019 by

How Celia Paul’s art resonates with that of the Brontë sisters

Celia Paul, The Brontë Parsonage (with Charlotte’s Pine and Emily’s Path to the Moors), 2017. Oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 29 1/4 in. © Celia Paul. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Seven paintings by the contemporary British artist Celia Paul (born 1959) are on view through July 8, 2019, in the Huntington Art Gallery. The eponymously titled exhibition “Celia Paul” originated at the Yale Center for British Art in 2018 as a show guest curated by Hilton Als, Pulitzer Prize–winning staff writer and theater critic for The New Yorker. The works on display were selected by Als in collaboration with the artist and testify to their friendship.

Beautifully installed in the Focus Gallery on the second floor of the Huntington Art Gallery, the “Celia Paul” exhibition invokes works by some of the 19th-century painters in The Huntington’s permanent collection on display in adjacent galleries, such as those by J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, who also explored light and landscape. That resonance appealed to Chief Curator of European Art Catherine Hess, who brought the exhibition to The Huntington.

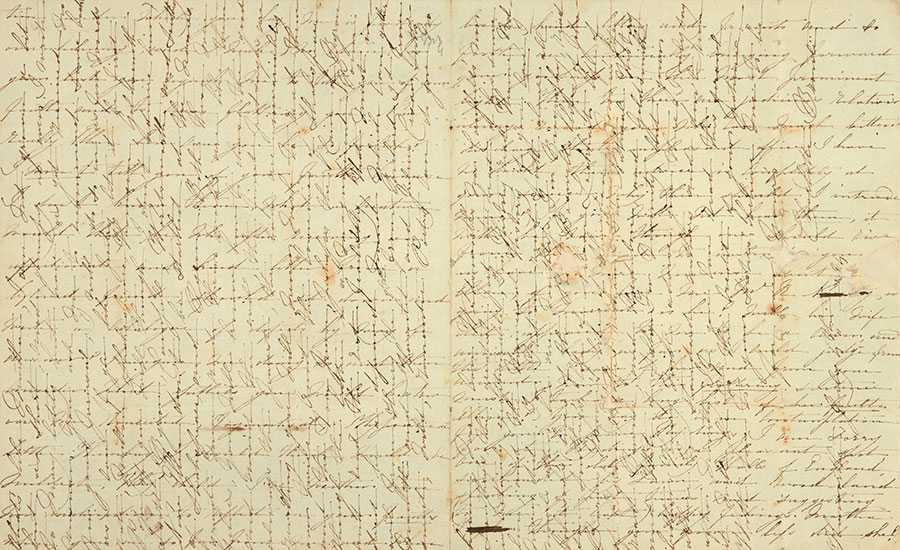

Cross-written letter by Charlotte Brontë to Ellen Nussey, July 4, 1834. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One of the seven paintings in the show, The Brontë Parsonage (with Charlotte’s Pine and Emily’s Path to the Moors), 2017, suggests that the painter feels a connection to her compatriots, the talented Brontë siblings: Charlotte, Emily, Anne, and their brother, Branwell. Hess confirms that Paul’s interest in the Brontës is deep and ongoing: “Paul does feel a great kinship with the Brontës and, given the holdings of our library, we are fortunate to be able to consider firsthand artistic and literary works that share similar undercurrents of yearning and introspection.”

Through this Brontë reference, the show speaks to the 19th-century material in The Huntington’s library: manuscript poems by Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë. The library also holds more than 100 letters written by Charlotte Brontë (1816–1855) to her childhood friend Ellen Nussey (1817–1897). Charlotte met Ellen at the Roe Head School in their early teens, and the friends exchanged letters of great intimacy and detail.

There are many parallels between the early lives of Celia Paul and the Brontë siblings. Paul was born to missionary parents in India; her family returned to England when she was still a child. The Brontë patriarch, Patrick, was an Anglican clergyman. After his wife passed away (soon after giving birth to Anne), Patrick raised his children with his sister-in-law.

Celia Paul, Clouds and Foam, 2017. Oil on canvas, 25 x 22 3/8 in. © Celia Paul. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Celia Paul and the Brontës grew up in families that were tight-knit and creative. As children, they played with their siblings in a remote part of the British countryside and found artistic inspiration wandering outdoors. The Brontë children, and in particular the younger sisters, spent much time outdoors together in Yorkshire. They often wrote the landscape into their stories and their stories into the landscape, inventing imaginary worlds that they chronicled in small handwritten booklets.

A century and a half later, Paul and her sisters played in virtually the same scenery. The Paul family vacationed in West Yorkshire near Haworth House, where the Brontës grew up. The subtitle of Paul’s painting of Haworth House indicates that she actively imagined the young Brontës there. “Charlotte’s pine” appears as a backlit cross hovering over a series of gravestones, from which extends “Emily’s path to the moors.”

The other six paintings by Paul on view share thematic and gestural concerns with the work of the Brontës. Five of them are landscapes or seascapes. Paul, like the Brontë authors, imbues the natural world with intense, introspective emotion. Her brushwork emphasizes the brightness of the sky and the dampness in the air at different times of day, drawing attention to moments of heightened significance. Such paintings assert a connection between landscape, memory, and familial intimacy. Paul began painting seascapes soon after her mother’s death in 2015, believing that, if her mother was anywhere, she was part of the sea.

First page of Charlotte Brontë’s letter to Ellen Nussey, Oct. 24, 1839. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Brontës are perhaps most famous for their depictions of moors in their novels. Think of the heather-covered hills that surround Wuthering Heights, the moorland farmhouse in Emily’s novel of the same name, and the isolated Thornfield Hall in Charlotte’s Jane Eyre. The moors are a region of danger and abandon in the novels—the place where characters venture when overcome by passion.

Charlotte herself drew avidly and created characters who expressed their suppressed emotions through visual art. We might recall the scene in Jane Eyre in which Rochester examines Jane’s drawings and, impressed by their evocative power and peculiarity, asks, “And who taught you to paint wind? There is a high gale in that sky, and on this hill-top.”

We know that Charlotte Brontë was interested in emotionally charged weather from her personal as well as her published writing. Charlotte saw the sea for the first time on a trip to the seashore with Ellen Nussey in early 1834—probably the best vacation of her life. She writes to Ellen on Oct. 24, 1839: “Have you forgot the Sea by this time Ellen? is it grown dim in your mind? or you can still see it dark blue and green and foam-white and hear it—roaring roughly when the wind [is] high or rushing softly when it is calm?”

Celia Paul, My Sisters in Mourning, 2015–16. Oil on canvas, 58 1/8 x 58 1/4 x 1 3/8 in. © Celia Paul. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

In addition to the seascapes, the Paul installation includes a more traditional funereal scene, My Sisters in Mourning, 2015–16, painted after the death of Paul’s mother in 2015. Using a subdued color palette, Paul portrays her sisters seated closely together, conveying solidarity and composure—the sisters a bulwark against the dissolution of family ties. Their mother, one of Paul’s most frequent subjects, was seated in the center of Paul’s painting (not on view) of her family done on the occasion of her father’s death in 1984.

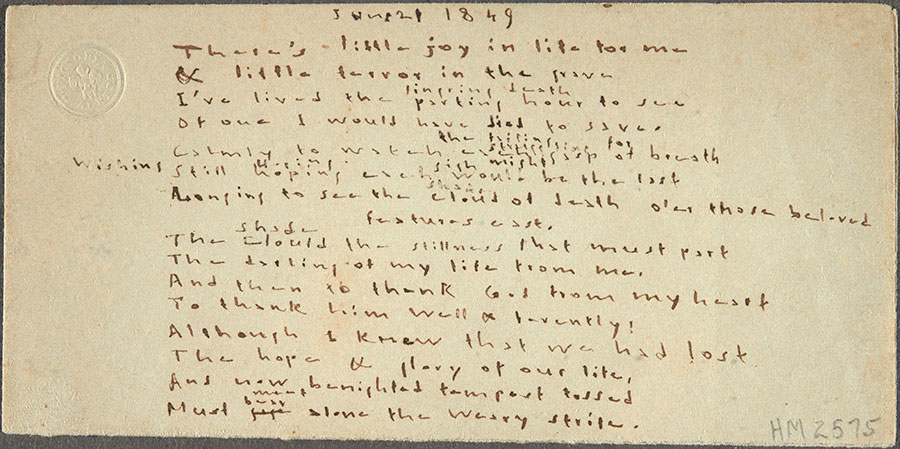

Charlotte Brontë also turned to art to express grief and familial love. Although Charlotte lived only to age 38, she outlived all five of her siblings. Among the poems in The Huntington’s collection are two that she wrote upon the deaths of Emily in 1848 (at age 30) and Anne in 1849 (at age 29). Charlotte had returned to the sea with Anne in late 1848 on the recommendation of doctors who thought the coastal air might cure Anne’s respiratory ailments. Anne died there, and upon returning home, Charlotte wrote a poem about her sister’s death on a scrap of paper in small, tight handwriting. The poem begins:

“There’s little joy in life for me,

And little terror in the grave;

I’ve lived the parting hour to see

Of one I would have died to save.”

Charlotte Brontë’s poem—dated June 21, 1849—about her sister Anne, who had died on May 28, 1849. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Luminous and heartfelt, Celia Paul’s new works capture place and mood in a way that the Brontës surely would have recognized as kindred.

The “Celia Paul” exhibition has been organized by the Yale Center for British Art, in collaboration with The Huntington. It is made possible by generous support from Victoria Miro, London/Venice and Laura and Carlton Seaver.

Karla Nielsen is curator of literary collections at The Huntington.