Accounting for Freedom

Posted on Mon., July 20, 2020 by

Curator Olga Tsapina discusses the account book of an Underground Railroad operator.

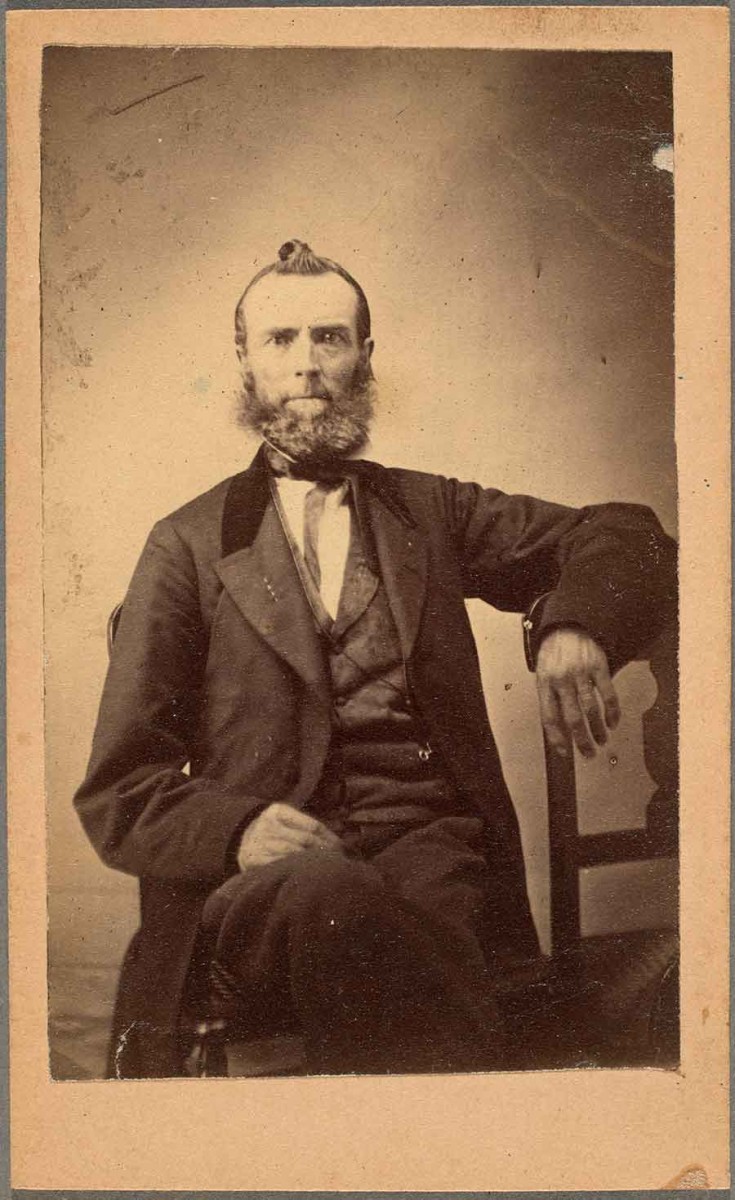

Zachariah Taylor Shugart (1805–1881), a Quaker abolitionist who operated a stop on the Underground Railroad at his Michigan farm, ca. 1864. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington is home to extensive collections documenting the history of slavery and abolition in the United States and the Atlantic World. In 2019, the institution acquired a collection of papers of Quaker farmer Zachariah Taylor Shugart (1805–1881), who operated an Underground Railroad stop in Cass County, Michigan. Among the papers is Shugart's account book, which records the names of 137 men and women he sheltered on their way to freedom. This manuscript is the first item that has been digitized for the new digital collection of slavery and abolition materials. To learn more about this new acquisition and its unique importance, Frontiers Senior Editor and Writer Usha Lee McFarling spoke with Olga Tsapina, the Norris Foundation Curator of American History at The Huntington.

Huntington Frontiers: Can you describe this account book and its significance to historians?

Tsapina: This is an ordinary-looking notebook, with double-entry accounts of debit and credit. These accounts were ubiquitous in 19th-century America, some embedded in personal journals, others confined to accounting ledgers.

Accounts tend to pale in comparison with diaries or journals, but records of sums owed and due, goods purchased and sold, and services offered and received also make up life narratives and sometimes tell remarkable stories. This is true for other accounts books collected by The Huntington, for example a ledger kept by Susan B. Anthony during her campaign for women’s rights and the notebook of abolitionist John Brown.

In an era when the cost of paper and writing implements was considerable (in 1859, Susan B. Anthony paid 31 cents—or $9.64 in today’s prices—for her notebook and pencil), people tended to maximize the use of their stationery. In 1856, amidst the civil war in Kansas, John Brown used his old account book kept while he was a sheep-trader in Akron, Ohio, to draft articles of enlistment for his antislavery militia and record the names of those wounded in the Battle of Black Jack.

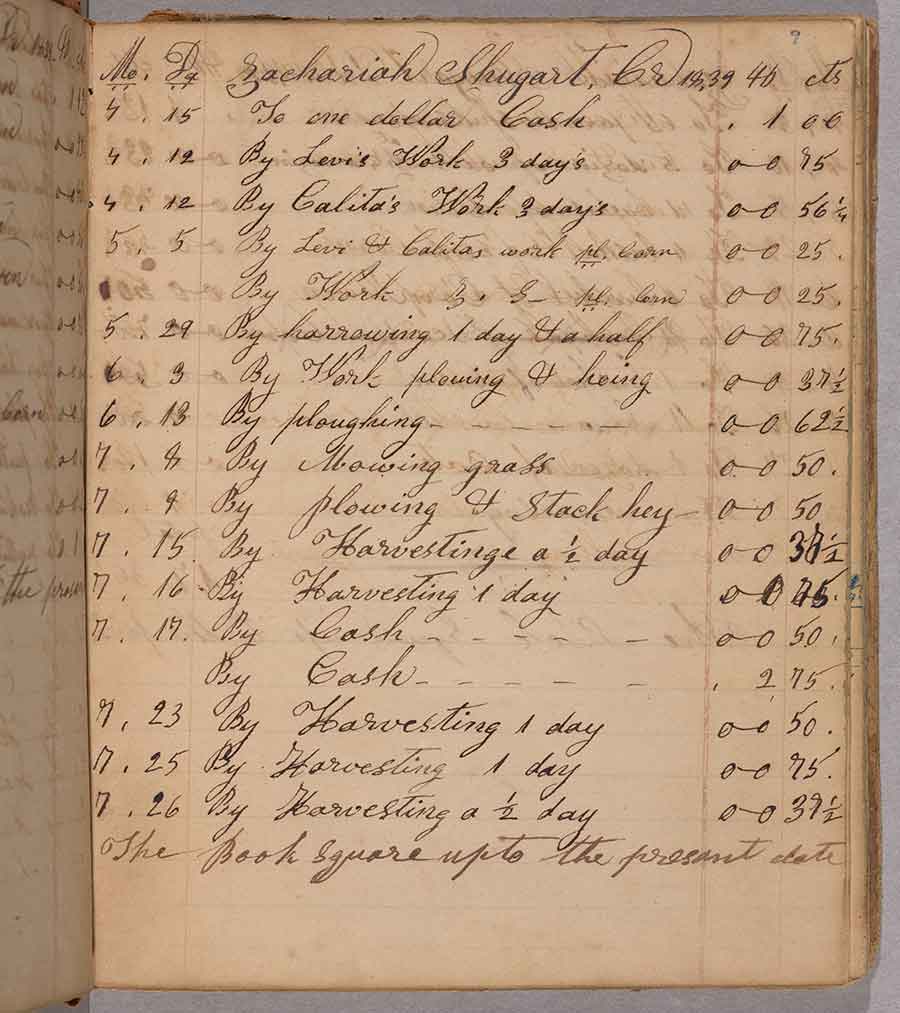

Pages 96 and 97 in Shugart’s account book (1851–53) listing enslaved people he helped usher to freedom. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Zachariah T. Shugart was no exception. His book documents his life from 1838 to 1853. Among pages of records of expenses and earnings, there are lists of “Runaway Negroes,” 137 enslaved men, women, and children assisted by Shugart on their road to freedom.

HF: How will this account book help deepen our understanding of the Underground Railroad?

Tsapina: This is an exceptionally rare contemporaneous record of the operation. The scholarship on the topic has long relied on interviews, reminiscences, and memoirs created after the Civil War, when the Underground Railroad became the stuff of legend. In the words of historian Andrew Delbanco, “To read postwar accounts of the prewar years, one might think that every farmhouse in the North had been a station, everyone’s father or grandfather had been a conductor.” Another kind of primary source, the fugitive slave narrative that became popular in the last two decades before the Civil War, was also memoir, often fictionalized by white journalists to fit the mold of a bestselling story of a heroic outlaw, a survivor, or a rescued victim.

These resources, however valuable, are still secondhand accounts. Records created by the operators of the Underground Railroad are few and far between—and therefore precious. The activists who made up the rather loose network of the Underground Railroad usually avoided keeping records, knowing perfectly well they were breaking federal law.

Olga Tsapina, the Norris Foundation Curator of American History at The Huntington, delves into the Shugart materials. Photograph by Aric Allen.

This account survived partly because Shugart felt secure enough to record the names of the runaways in his book. It is not clear why Shugart made these records. It might have something to do with yet unknown technical details of the operation. Or he did so merely out of habit—recording everything that happened in his life.

There was, of course, a good chance that his account book could have fallen into unfriendly hands. Shugart was very familiar with the legal consequences of helping refugees from slavery. His account book includes a long list of legal expenses incurred during the litigation over a conflict with a band of Kentucky slave catchers who raided his farm in August 1847.

That standoff, however, took place before Congress passed the draconian Fugitive Slave Act in September 1850. The risk increased exponentially, as the law not only compelled all U.S. citizens to assist federal officers charged with capturing runaways, but also mandated harsh civil and criminal punishment for anyone who failed to do so, much less resisted them. Shugart’s lists of “Runaway Negroes” are dated from 1852–53, demonstrating that he operated in clear defiance of the law. The account book also shows that Shugart and his abolitionist neighbors made no attempt to conceal their activities. This was not unusual in communities where antislavery sentiment prevailed.

Historians knew of the account book that remained in the possession of Shugart’s family. It is, for example, mentioned in Mary Ellen Snodgrass’s encyclopedia of the Underground Railroad. However, until now, only a 1964 typescript copy of the account book’s fugitive list, housed at the Niles Community Library in Michigan, has been available. Today, scholars and the public can explore the entire original manuscript online.

In addition to containing the names of 137 men, women, and children who passed through Shugart’s farm while trying to reach freedom in Canada, Shugart’s account book also contains everyday details of his business life. Photograph by Aric Allen.

HF: Most people think of ledgers as long lists of numbers and not particularly interesting as narratives. Why is this book different?

Tsapina: It doesn't much differ from similar ledgers kept in countless households across the United States. But what is remarkable about it is the meticulousness of Shugart's record-keeping. This, in part, stemmed from the Quaker work ethic, which emphasized frugality, honesty, and accountability. It also reflects Shugart’s personality, which compelled him to record everything that happened in his life. In a way, the account book reads almost like a diary in numbers.

HF: What does the account book tell you about Mr. Shugart?

Tsapina: The Shugart family is well known to scholars of the Underground Railroad. Zachariah T. Shugart’s brothers John and George, who lived in Indiana, were also conductors of the local line. Zachariah is listed in all major works on the subject. However, all information about the man previously came from reminiscences and memoirs.

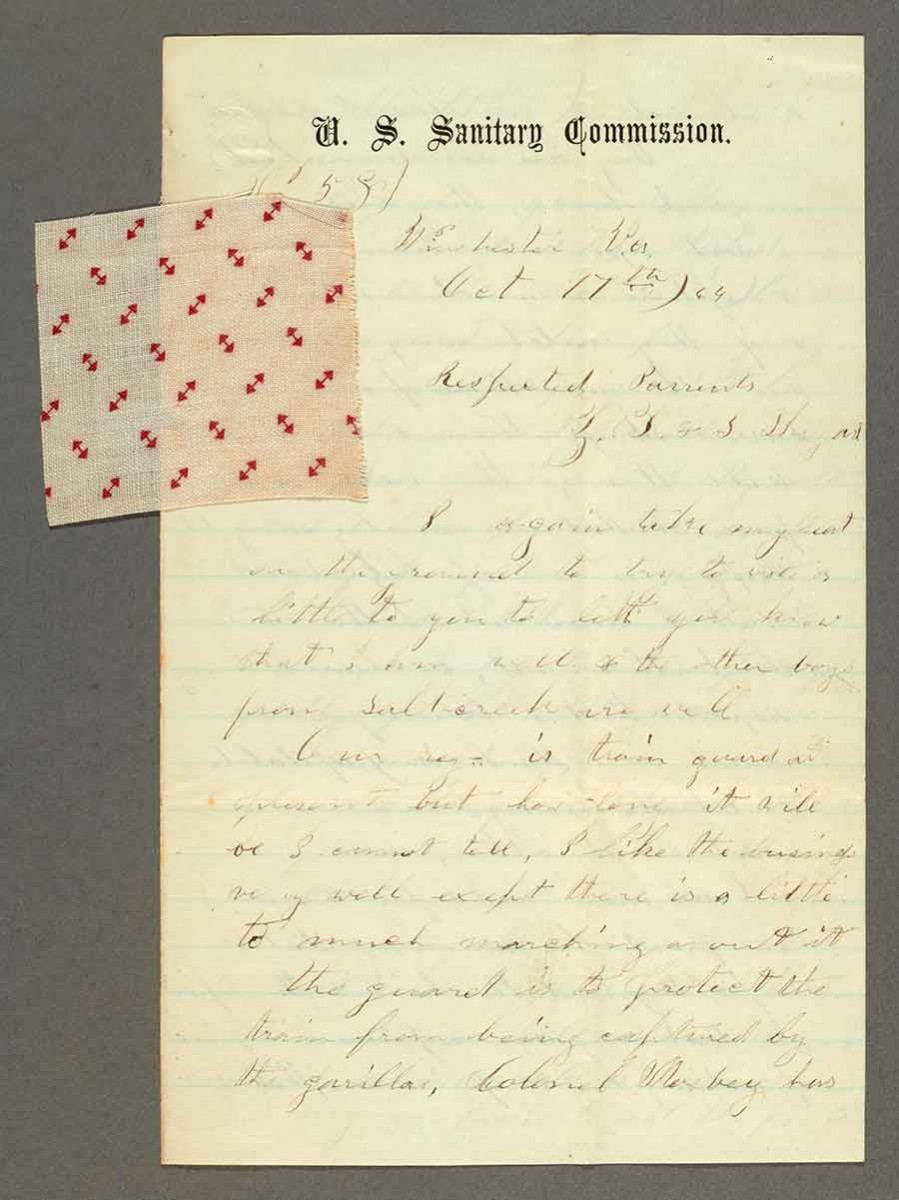

The account book and the accompanying documents, which include Shugart’s diary that he kept from 1866–67 and the Civil War letters of his son Joseph, is the first cache of archival materials from this remarkable family to surface anywhere.

In the account book, we first meet young Zachariah Shugart in Indiana, where his family, along with other Quaker families, had moved from their native North Carolina in the late 1820s. They were looking expressly to settle in a place that did not condone slavery and found it farther north and west.

The Shugart papers include this 1864 letter from Shugart’s son Joseph, written just two days before Joseph was killed at age 24 at the Battle of Cedar Creek in Virginia. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Through the account book’s first entries, we get to meet Shugart’s wife, Susannah, and their children, Levi Harris Shugart, Kelita Davis Shugart, and Malinda Shugart. The two boys, Levi and Kelita—eleven and nine at the time—earned some money helping out at neighboring farms. We also get to meet other Quakers from North Carolina.

We then follow the family to Cass County, Michigan. The Shugarts arrived there with their newborn Lucinda. Two years later, they greeted the arrival of their youngest son, Joseph. We see Shugart acquiring more land; opening a boarding house, which also served as an Underground Railroad station; building a “Meeting House”; and even wading into the pharmaceutical business, selling “Dr. Caldwell’s pills.”

The account book lists expenses for the education of his children, including the cost of medicine for his daughter Malinda, who died when she was 16. Levi would grow up to become a prosperous Midwestern farmer. Kelita would become a physician with a successful practice in Iowa and, in 1870, move to Southern California to become one of the founders of the City of Riverside. Joseph would enlist in the Union Army and be killed in battle in October 1864.

HF: It tells a remarkably detailed story.

Tsapina: The entries describe to whom the payments were going and for what. If an installment payment was made, Shugart showed which installment it was. If he was paying something jointly, he would include his partner’s name. With such details, you can piece together a very vivid and almost complete picture of the life Shugart—and others— led in his village in Cass County.

A selection of images from the Shugart archive. Photograph by Aric Allen.

HF: What is the next step now? Will the rest of the Shugart materials—the photos and letters—also be digitized?

Tsapina: The account book, which has been digitized and uploaded in the Huntington Digital Library, is the inaugural piece in our new digital library collection of slavery and abolition materials. We plan to add more materials to the collection over time as we know there is bound to be great interest among scholars, public historians, artists, writers, and genealogists—especially people tracing the history of enslaved African American families.

Descendants of the formerly enslaved Americans tend to lack the luxury of having family correspondence or other archives at their disposal. The only written records available are usually meager entries in estate inventories or bills of sale. Shugart made a point of recording the refugees’ names as well as he could. Sometimes he could not catch a name, and sometimes the person chose not to volunteer it, hence there are such entries as “Ellen Something.”

HF: How do you see this account book as different from plantation estate inventories, which also listed enslaved people?

Tsapina: There is a major difference. Indeed, Shugart’s records hardly provide more detail than, say, an estate inventory. These are mere snapshots of persons in a particular moment that tell us next to nothing about their lives or their families. However, these snapshots are rare glimpses into lives that have broken free, however temporarily, from the dehumanizing infrastructure of human bondage. Shugart listed the people traveling on the Underground Railroad not as commodities, but as human beings and as fellow Americans who were suffering unfair persecution.

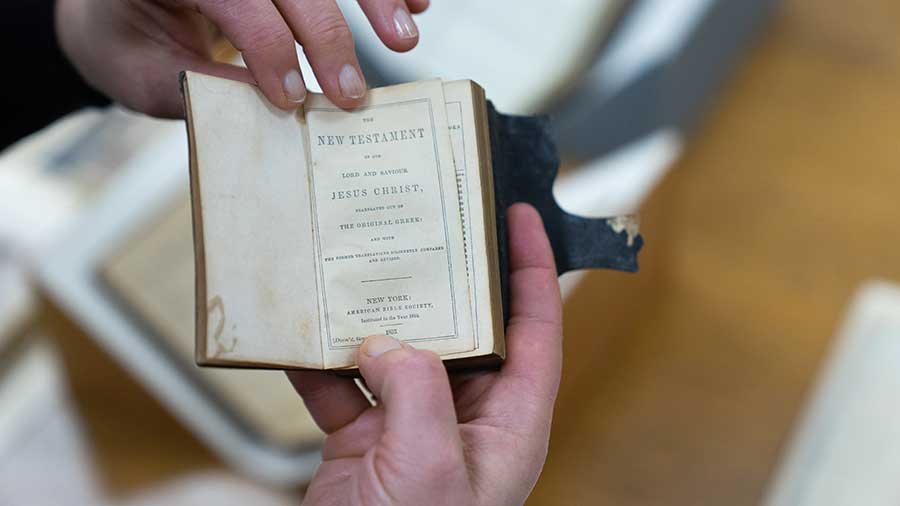

Olga Tsapina holds a small edition of the New Testament that Zachariah Shugart carried around in his pocket. Photograph by Aric Allen.

HF: When you learn about the Underground Railroad, you think of the people who ran it as extraordinary heroes. Shugart’s account book lacks the heroics that are often associated with it. What we see is an ordinary, although obviously deeply moral man, who helps the refugees from slavery while living a fairly conventional life.

Tsapina: This is a very important point. There has been a certain amount of mythologizing of the Underground Railroad. For some, it was made up of valiant resisters, and for others, it was a network of lawless, self-righteous fanatics who undermined the Constitution. Shugart and his friends and neighbors were neither. Shugart’s account book, while lacking in heroics, reflects the matter-of-fact nature of the antislavery activism of the time. These were farmers, storekeepers, teachers, doctors, laborers, and homemakers who helped the runaways because their faith commanded them to lift up the voiceless and the oppressed. It was no accident that Shugart’s family also preserved a small edition of the New Testament that he carried around in his pocket.

Not all Quakers felt this way. Many thought it was their duty as law-abiding citizens to comply with the law and return the fugitives to slavery. The question of whether the Friends should abide by the fugitive slave law caused a split among the Quakers of Cass County. In 1843, Shugart was among those who broke away from the meeting at Birch Lake to form the Young Prairie Anti-Slavery Society.

It is also important to keep in mind that while people like Shugart did their best, only a tiny fraction of runaways reached freedom. We don’t even know whether all the 137 men, women, and children listed in his account book made it to freedom and safety in Canada.

As we celebrate the lives of the conductors of the Underground Railroad and the people who managed to escape slavery, we must always keep in mind countless Americans, men and women, old and young, who were hunted down and returned, in leg irons and spiked collars, to die in bondage or to wait for some 12 years until American slavery was written out of the Constitution.

Usha Lee McFarling is senior writer and editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.