The Autobiography of a Garden

Posted on Sun., July 19, 2020 by

Andrew Raftery’s ceramic plates capture the cycle of the seasons in fine detail.

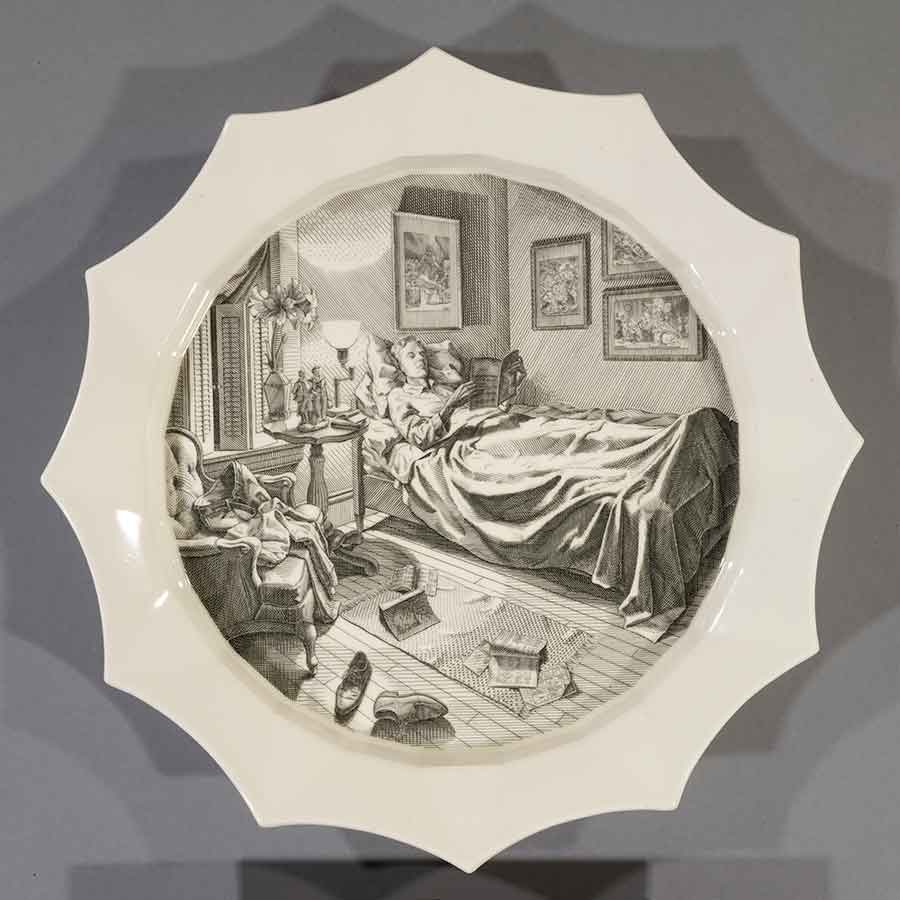

Andrew Raftery, January: Reading Seed Catalogs, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

When the COVID-19 health crisis that has upended all our lives is over and The Huntington is again fully open to the public, one life-affirming pleasure awaiting visitors will be found in The Huntington Art Gallery’s Works on Paper Room. There, displayed against walls of saturated blue, is a resonant, even elegiac, visual narrative. The story that it tells of life and renewal is not on paper, but on 12 uniquely bordered, luminous, ceramic plates revealing in keenly observed detail “The Autobiography of a Garden,” a month-to-month evolution of a real-life garden in Providence, Rhode Island.

The exhibition, on view through July 5, 2021, is the work of American painter and printmaker Andrew Raftery and is the product of his inventive, modern-day approach to the transfer of print images onto ceramic, a process dating back to the mid-18th century.

Raftery, a professor of printmaking at the Rhode Island School of Design, specializes in engraved scenes of contemporary American suburbia. His portfolios, Suit Shopping (2002) and Open House (2008), were collected by the Whitney Museum of American Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cleveland Museum of Art, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the British Museum. He is a 2008 fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, as well as a member of the National Academy of Design.

Andrew Raftery, February: Planting Seeds, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

Eight years in the making, “The Autobiography of a Garden” marks the realization of Raftery’s long-held desire to transfer his engravings to a potentially functional ceramic object, rather than paper. His visual story at The Huntington, told in fine-lined detail and concurrent with the garden he designed and planted at his mother’s home, begins in January, on a plate entitled “Reading Seed Catalogs.” It depicts Raftery himself, perusing a seed catalog while lying in bed. The walls of his room are hung with framed prints by old masters; jeans and a pair of long johns are thrown over an armchair. Other seed catalogs lie discarded on a rumpled throw rug beside the bed.

In February, Raftery has portrayed himself in robe and slippers, sitting at his kitchen table, planting seeds in a container. A display of ceramic transfer ware plates, representative of Raftery’s own large collection of antique dishes—some nearly 200 years old—covers the walls; more of these antiques sit in the kitchen sink.

Transfer ware, once wildly popular, fell out of fashion some time ago. Raftery sought to reclaim it, working through a painstaking process involving ceramics, engraving, printing, and several experts in each area, to bring his work to life. "The plates in our collection are very much a part of our lives whether they’re on the walls or on the table,” maintains Raftery. He feels a kinship, he says, to the workers and designers who made them and views them as a microcosm “of the way people lived, how they imagined the world, their desire for decoration in their lives.”

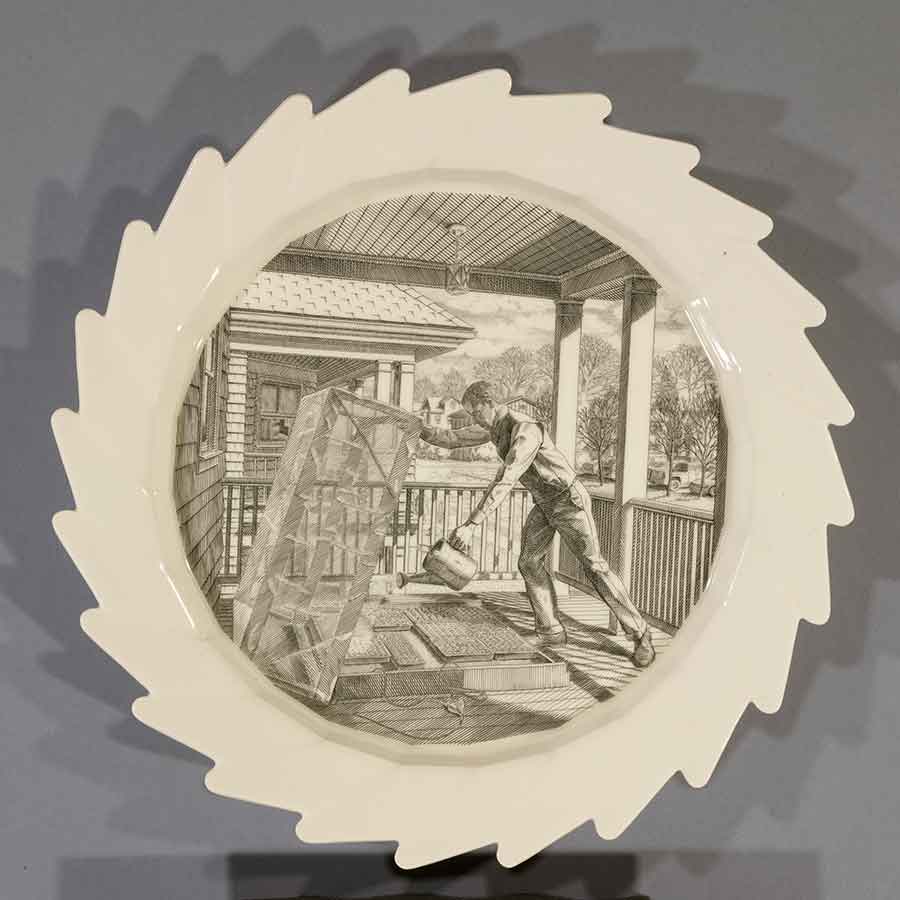

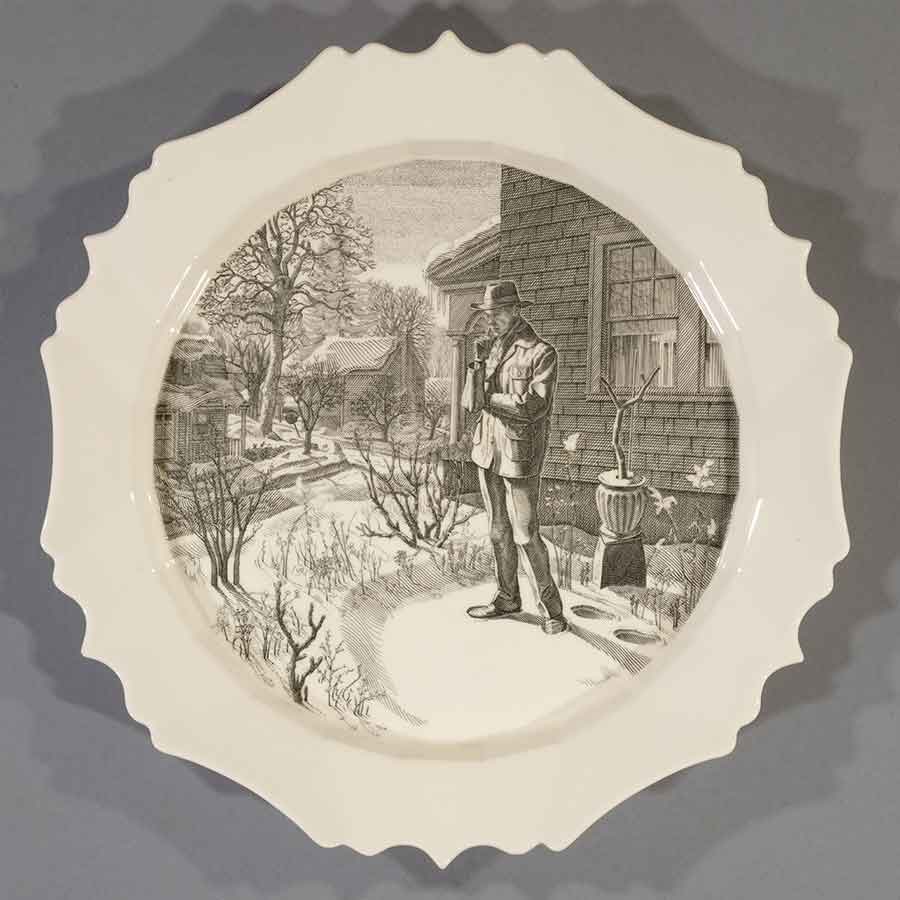

Andrew Raftery, March: Watering the Cold Frame, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

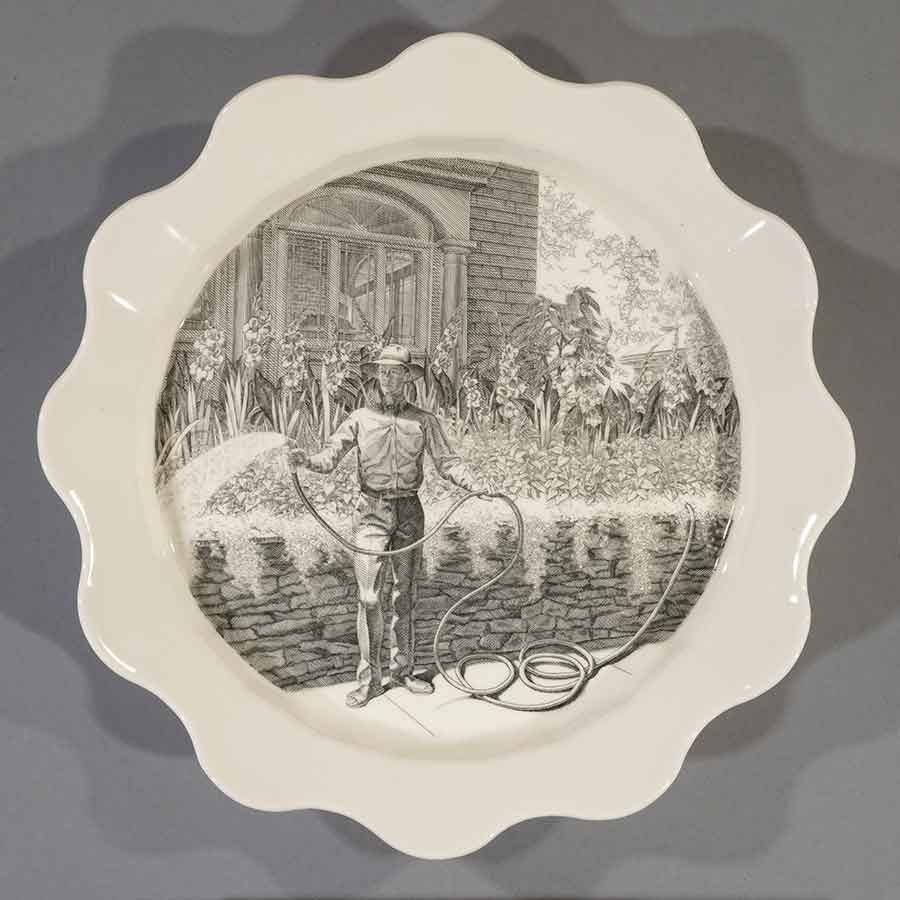

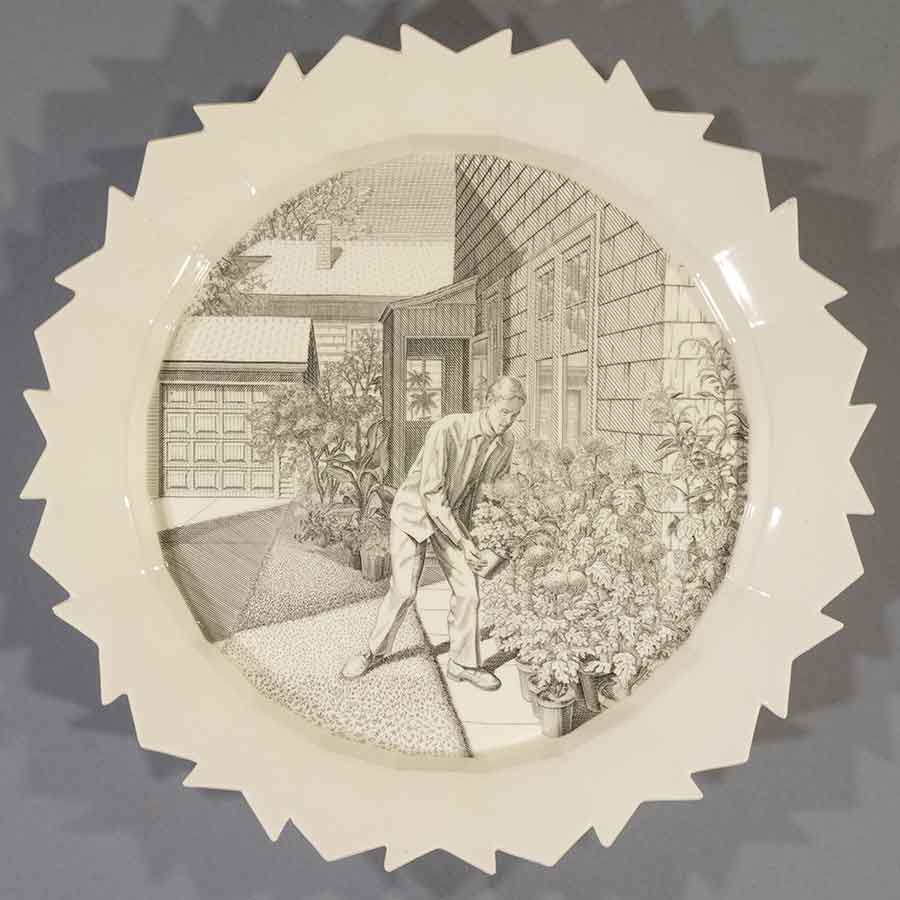

The year in the garden progresses from plate to plate. Scenes change according to the months they represent: bushes and flowers grow and blossom; plants are trimmed, weeded, and watered, and die away; bulbs are gathered, and, finally, in December, there are a barren winter landscape and Raftery’s footsteps in the snow. (Drawing and painting a garden as it grew presented a unique challenge: “If one year I didn’t get to draw the tulips in April,” Raftery states, “I had to wait until the next April to do it.”)

Stamped on the back of each plate, a cartouche with ornamentation related to the design on the front displays such plainly descriptive titles as “Cultivating the Lettuce,” “Watering the Cold Frame,” “Bringing in the Chrysanthemums.” The unique edges of the plates, too, have meaning. The clockwise, saw-toothed edge for March, for instance, represents time “springing forward.”

The “understory” of the plates, Raftery explains, encompasses the time that he spent with his mother (who just turned 90) during the project, “and how special the garden was as an experience at her house and how it relates to her work as an artist.” Raftery’s mother, a painter, employs the flowers in her garden as subjects in her expressionist works. “And it definitely has to do with the passage of time; it definitely deals with mortality,” Raftery adds. “But then it has the positive side that makes gardening so wonderful: there’s always next season.”

Andrew Raftery, April: Edging the Beds, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

The evocative tone that Raftery imparts to the work comes, in part, because he includes himself in these deceptively simple narratives—clearly engaged in what he is undertaking at that moment and unaware of being observed. What might seem a near-haunting quality of his work is situated, perhaps, in what he describes as “the in-between areas.” “The way the shadows hit the grass,” he explains, “or the quality of light in the sky, or the way the brilliant sunlight hits the shingles—those types of things we don’t necessarily notice directly, but they inform our understanding of the whole image.”

Spotting details that might be missed during a first, second, or even third viewing of the plates is one of the pleasures of Raftery’s exhibition at The Huntington. Rich in architectural and natural elements, the plates’ designs offer a wealth of small, everyday details that upon close examination convey a sense of discovery: an electrical cord on a porch, a car barely visible on a nearby street, carefully delineated foliage, the clothes worn by Raftery’s gardener-avatar.

There is unexpected humor: A stop sign listing precariously to one side on a street corner is subtly visible in two of the scenes. “Providence is such a beautiful city,” says Raftery, “but sometimes our maintenance isn’t what it could be. Across the street from my mother there is a stop sign that somebody crashed into. Trees have come down, different people have moved in and out, but that stop sign is still angled like that. It’s a reminder that this is a real place.”

Andrew Raftery, May: Cultivating Lettuce, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

"The attention to detail in the plates is stunning," says Catherine Hess, The Huntington's chief curator of European Art. "And there is this sense of delight that comes through. It's a wonderful match for us and our collecting activities: Raftery is an American, yet it's a British art form, it involves prints, it involves ceramics, it involves plants, and it involves the poignant topic of the passage of time—a nice thing to contemplate in a garden."

“The Autobiography of a Garden” happened in several stages and across a variety of media. Raftery first made sketches, then detailed drawings of plants and architectural elements. He added images of himself as a character in his narrative, based on photographs, to circular wash drawings showing the basic composition of each scene. “I would set up a tripod and pose for that,” he says. To refine the likeness and physical presence of his character in the finished paintings, Raftery crafted wax maquettes to use as scale models. After tracing his finished paintings on clear acetate and scanning, shrinking, and transferring the black-line tracings to sheets of copper, he began engraving. Each engraved scene, he notes, took “three or four months, just working it out by carving it line by line.”

Andrew Raftery, June: Training a Passion Vine, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

In a video of Raftery at work on the project, he gazes intently through heavy-duty magnifiers as he leans in to make small, precise marks with a single engraving tool (a burin) on a flat sheet of copper. The intimacy of the process is striking. “It seems like it’s the whole world,” Raftery agrees. “I’m just concentrating on moving from mark to mark, and I’m always thinking about the relationship between the spacing and the width of every mark in relationship to any other marks that are in the image. Even though I’m looking very carefully, so much of it happens by feeling it with my body. There’s a real relationship between what’s happening in the mind, through the eyes, and then through the body, and then sort of feeling how the tool is going through the copper. It is extremely involving.”

Just the act of building up the lines in an engraving, Raftery notes, “keeping track of how deep they are and how far apart they are, considering how every line relates to the whole, is such a powerful experience. Stroke to stroke to stroke,” he says, “it doesn’t seem small when I’m doing it. It seems really vast to be involved in that plate. I find that to be quite a magical thing. I’m always so happy when I’m teaching engraving to my students and they get the feeling that they’re in the plate and it’s the whole world while they’re working on it.”

Andrew Raftery, July: Fertilizing, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

Working with ceramics, however, was a new venture for Raftery, who brought his unique plate series to fruition through a lengthy, collaborative process. After determining the plates’ shapes by sculpting them in paper, he finalized the shapes in Sintra board, with the help of RISD students. His late colleague at RISD, ceramist Larry Bush, whom Raftery calls “the absolute technical director” for the project, experimented with more than 200 clay mixes and firings at different temperatures to come up with a custom clay that would resemble the Wedgwood creamware of the 18th century.

“I could have had Larry make the plates for me and design them,” Raftery says, “or I could have purchased plates to use. But in looking at my [antique] plates, I noticed how robust the shapes are. They have scalloping profiles, and there’s a kind of joyful quality to the shapes themselves. I think it’s because of those strong shapes they are able to hold so much decoration.”

Special molds had to be made for the hydraulic press; pressing out the plates alone (150 per shape) took two full summers. The plates were then trimmed, bisque-fired, and glazed; when the glaze persisted in "crazing"—or cracking—RISD graduate student Jack Yu found a solution.

Andrew Raftery, August: Deadheading, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

Learning how to transfer his prints onto the ceramic plates, too, was a difficult proposition because the industry in England, which produced "millions of pieces using tissue transfers" from the 19th century on, Raftery notes, "really has fallen apart. I had a hard time finding anybody who could tell me how to do it." With materials developed for that process in limited supply or no longer available, Bush suggested that in lieu of tissue transfer paper, a new material used for digitally printed decals might work. It did. “It’s actually a layer of acrylic that has glaze in it,” Raftery says. “It seems like the worst possible material to print on because it’s basically plastic, but it took an incredibly beautiful impression. It takes every molecule of the ink out of the copperplate. We then figured out how to do the application onto the ceramic with lamination and waterslide transfer, and it turned out great.”

(Larry Bush passed away in 2019, leaving his colleagues devastated, Raftery says. He is working to help bring attention to Bush’s own fine art sculptural ceramic works.)

Andrew Raftery, September: Mowing, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

Despite the muscular robustness of the process that created them, the plates, with their fine detail and relative fragility, convey a delicate aesthetic. “That is the case with almost all printmaking,” Raftery says. “You have those giant presses and the pressure needed to make the prints, so it is this interaction between machines and people. But the focal point is always going to be that final work of art that has its own properties, its delicacy, its kind of presence in the world."

Raftery, who made his first print at age 11, grew up in Washington, D.C., surrounded by art. “My mother’s an artist, and I was just incredibly lucky to be in an environment where I had so much encouragement,” he says, “and constant inspiration with the National Gallery of Art there.” His immersive interest in prints and printmaking began at Boston University, where he studied engraving and attended exhibitions of works by such masters as 16th-century Dutch printmaker Lucas van Leyden and Italian Renaissance engraver Marcantonio Raimondi at the Museum of Fine Arts. Later, Raftery’s classes at the Yale Center for British Art, he says, “really solidified my love of British art that makes me so enthusiastic about The Huntington.”

Andrew Raftery, October: Bringing in Chrysanthemums, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

When at Yale, studying the history of print with Richard Field at the Yale University Art Gallery, Raftery sorted through “50 boxes of prints a week”; as a faculty member at RISD, he went through hundreds of engravings as consulting curator for the RISD Museum’s 2009–10 exhibition, “The Brilliant Line: The Journey of the Early Modern Engraver,” a show featuring engravers from the late 15th to the mid-17th century. That constant contact with those masterpieces, he feels, “has honed my eyes and kind of raised the bar for what I hope to do in my own work.”

Raftery cites two 20th-century artists as influences for his “Autobiography” project: French engraver Jean Emile Laboureur, whose “landscapes, the way he simplified the foliage, helped me make such a breakthrough in doing this work”; and British artist Clare Leighton—specifically, her 1948 “New England Industries” wood engravings commissioned for a set of 12 Wedgwood plates (part of Raftery’s personal collection). Like Leighton, Raftery says, “I wanted my prints on ceramics to be fully pictorial, to use every tool that I have in composition and drawing and the use of the marks to make the images.”

Andrew Raftery, November: Digging Dahlia Tubers, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

The Huntington’s acquisition of “The Autobiography of a Garden” was Raftery’s preferred choice, made possible by Richard Benefield and John Kunowski, who donated the funds for the purchase.

Having Raftery’s work at The Huntington “is kind of perfect for us,” says Melinda McCurdy, associate curator of British Art. Although the plates fit into the American collection, she observes, “they have been created using a technique derived from historic English ceramic ware, so that’s a link to our historic European ceramic collection, specifically the British collection. It is a nice way to be able to bring some American art into the European Gallery to make meaningful connections across the two collections. Scholarship is really paying more attention now to the similarities, and the exchanges, rather than simply the differences, between American and European art.”

Andrew Raftery, December: Contemplating the Snow, 2009–16, engravings transfer printed on glazed white earthenware, diameter: 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from Richard Benefield and John F. Kunowski. © Andrew Raftery.

“The Huntington is a wonderful place to experience British art, design, and decorative arts,” says Raftery. “I’m also very proud to be an American artist, and it’s so great to see the American artists featured at The Huntington. And then there’s just the unbelievable setting, with those buildings, and the gardens, and the range of experiences that are offered there. It’s unique among museums. It brings together so many things that I care about.”

Today, Raftery continues to cultivate his mother’s garden, and he is starting his own as well. “I’ve already planted probably a thousand little pots of seedlings,” he says, “and I’m getting ready to do a thousand more.”

Lynne Heffley is a freelance writer and editor based in South Pasadena, California.