Kaleidoscope

Posted on Fri., July 17, 2020 by

How a Scottish scientist's invention influenced 19th-century American decorative art

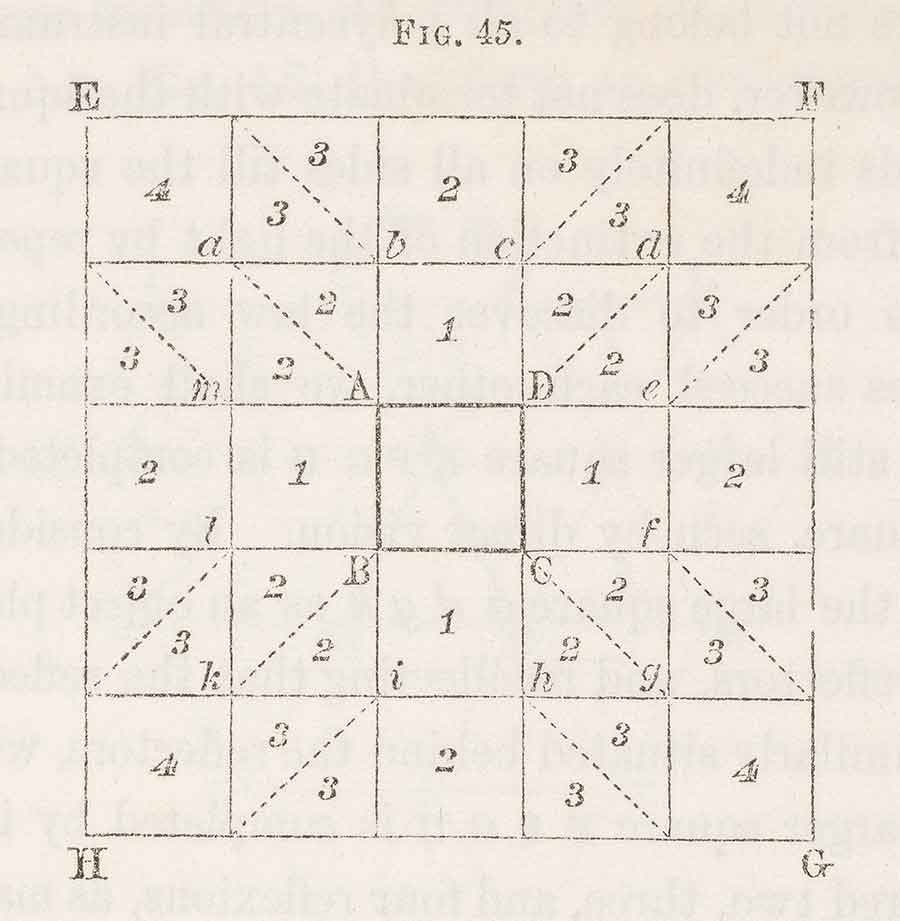

“On combinations of four mirrors forming a square” in David Brewster, The Kaleidoscope: Its History, Theory, and Construction (London, 1858), figure 45. Courtesy of The Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.

In 2016, The Huntington opened an addition to the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art, the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Wing, which features an ongoing exhibition of more than 200 works from the Fieldings’ esteemed collection of 18th- and early 19th-century American paintings, furniture, and related decorative art—some of which are promised gifts to The Huntington.

In 2020, The Huntington published the Becoming America catalog, which includes an essay by antiquarian and consultant Sumpter Priddy titled “The Kaleidoscope and the Fancy Style of the Early Republic.” In the essay, Priddy delves into the intellectual origins of the exuberant Fancy style of painted furniture and quilts in the Fielding Collection and the style’s connections to natural philosophy. The following passage is an excerpt from the essay.

Few objects have played a greater role in underscoring the combined power of light, color, and motion than the kaleidoscope. It was invented in 1816, quite by accident, during experiments with the polarization and refraction of light by the Scottish physicist Sir David Brewster (1781–1868). In an early phase of his research, he placed several long mirrors in a narrow brass cylinder to reflect an image as it traveled from its source to the viewer’s eye. When Brewster peered into the tube, he found that it transformed reality in unimaginable ways. He called his invention the “kaleidoscope,” from the Greek words for “beautiful image viewer.” Before Brewster could patent his design, competitors had purloined the concept and were selling inexpensive versions of cardboard and mirror plate to passersby on the street. The invention was an instant success, for it provided the perfect tool for understanding the powers of fancy and for demonstrating how light, color, and motion caught the eye and imprinted stunning images in the mind, where they could fuel the creative process.

Drunkard’s Path Quilt, ca. 1880–90, cotton, pieced, 87 × 87 1/2 in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection of Folk Art. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

British academics were intrigued by the charming images, but the colorful scenes provoked a much stronger response in America. There, the kaleidoscope seemed an ideal tool to whet one’s appetite for learning. This ingenious device would help Americans understand the power of the imagination in ways that were far removed from the literary sources that had long dominated British understanding of the subject.

In 1819 Brewster published A Treatise on the Kaleidoscope, in which he presented diagrams of distinct kaleidoscopes—those having two, three, or four mirrors grouped together in the tube—to show how a varied arrangement of mirrors would alter the image. He discussed the device’s ability to produce patterns for household decoration in record time: “It will create, in a single hour, what a thousand artists could not invent in the course of a year.” It could be used for a variety of objects, from stained-glass windows for cathedrals to household carpets and floorcloths. It was no longer necessary to devote significant time to drawing an entire design on paper. Rather, one could sketch a segment of the pattern and rely on the kaleidoscope to quickly expand the design into a variety of options.

Lone Star Quilt—Red, White, and Blue, ca. 1850, glazed cotton, pieced, 96 1/2 × 94 in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection of Folk Art. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Several of the diagrams that Brewster included had such a strong geometric character that they spurred public interest in an entirely new range of orderly design. The kaleidoscope had its greatest impact on American quilts. Whereas quilt makers on both sides of the Atlantic had traditionally focused on classical subjects or elegant foliage derived from nature, once the device was invented, they created a variety of innovative geometric designs that either emulated a kaleidoscopic view or looked to Brewster’s published diagrams for inspiration. Kaleidoscopes with two mirrors created a pattern that exploded outward from the center toward the edges in a large starburst. This was particularly obvious in the visual lines that radiated outward from the center of the quilt. In quilts of this type, the seams of adjoining wedges replicate where the image abuts a mirror—to create the star. Kaleidoscopes with a three-mirror system, joined together in a 30-60-90-degree triangle, likewise replicated the design, yet with subtle variety. Brewster depicted the pattern within an octagonal format—a diagram to which quilt makers often looked for octagonal piecework.

Box with Painted Geometric Design, ca. 1840, pine and paint, 6 1/2 × 14 1/8 × 9 in. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection of Folk Art. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Influenced by the kaleidoscope, women moved away from relying on large pieces of fabric and toward the use of tiny, multicolored pieces, carefully stitched together, to emulate the bits of glass in a kaleidoscope—and they expanded the quilts to completely cover a bedstead. It was only a matter of time before house painters transferred the patterns to canvas fabric to produce eye-catching floorcloths and table covers, expanding Fancy’s influence on American homes from wall to wall.

In addition to producing kaleidoscopes with two mirrors that created stunning explosions with colored glass, makers created examples with three and four mirrors, each of which produced a distinct design. Kaleidoscopes with a three-mirror system, joined together in a 60-60-60-degree triangle, repeated the image at the end of the tunnel time and again in a diagonal grid—thereby assuring that multiple replications of the image were firmly imprinted in the storehouse of memory. Indeed, kaleidoscopes with four mirrors facing inward in a square replicated the image in the center as an eight-pointed star. This produced even further options, not only for quilt makers but also for decorative painters. For example, a box from the Fielding Collection with a pink, green, red, and black palette evokes kaleidoscopic patterns.

Book cover of Becoming America: Highlights from the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection of Folk Art, 2020. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In this way, the kaleidoscope shaped Americans’ expectations for non-representational design and transformed middle-class homesteads. Although British kaleidoscopes were expensive devices made with hollow brass cylinders and highly polished mirrors, Americans were so infatuated by the device that they produced inexpensive examples of pasteboard or tinned sheet iron, and they relied on simple mirror plate rather than polished lenses. Foreign visitors to America were astounded to find that middle-class Americans were inspired by this “philosophical instrument.”

Although kaleidoscopes of two, three, and four mirrors produced their respective designs according to the dictates of geometry, their patterns were open to nearly endless interpretations by the viewer. Equally important, the range of ornament produced by the kaleidoscope embodied a new type of creativity that Joseph Addison had envisioned more than a century before when he observed the human capacity to “fancy to itself Things more Great, Strange, or Beautiful, than the Eye ever saw.” The kaleidoscope’s broad appeal in America helped its middle classes embrace abstract ornament.

Becoming America: Highlights from the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection of Folk Art is available online from the Huntington Store.

Sumpter Priddy is an antiquarian and consultant in Alexandria, Virginia.