Blue Boy Mania: How Gainsborough’s Masterpiece Colored Pop Culture

Posted on Wed., Jan. 12, 2022 by

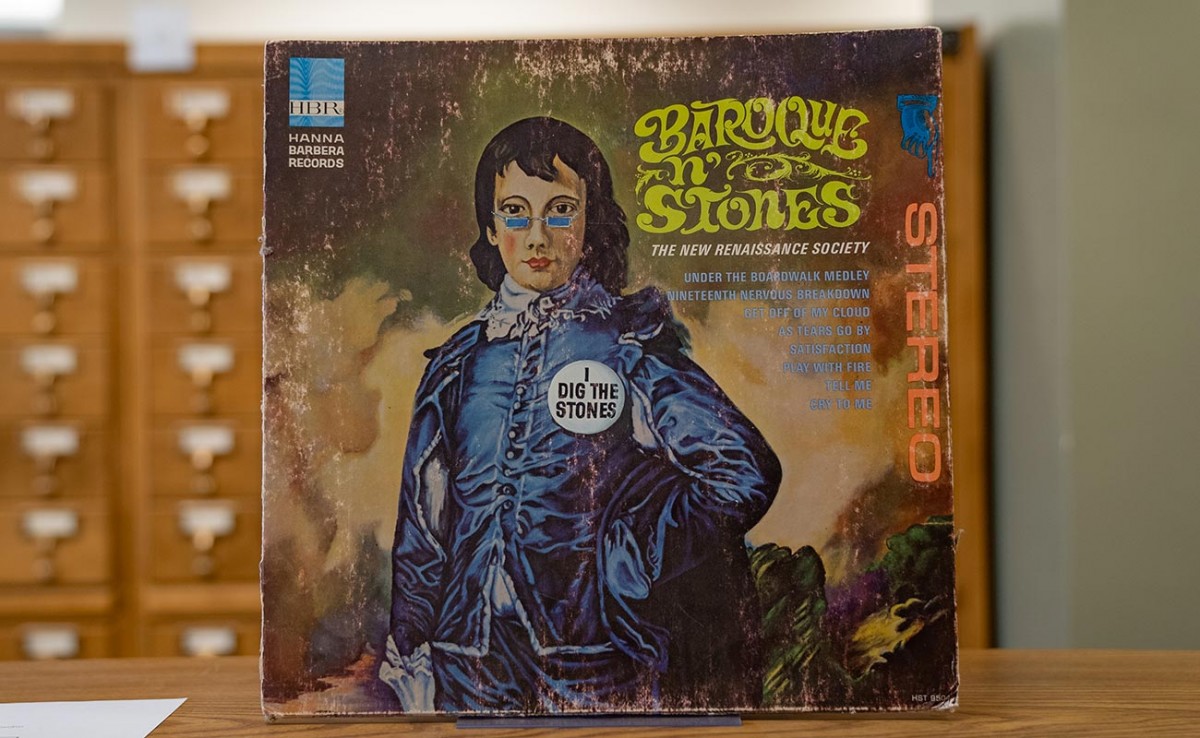

The New Renaissance Society, Baroque n’ Stones, Hanna Barbera Records, 1966. Blue Boy, wearing shades, graces the cover of this album of Baroque-style musical treatments of such Rolling Stones classics as “Get Off of My Cloud” and “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” Photo by Aric Allen.

Long before he ever visited or even heard of The Huntington, Board of Trustees member Simon Li came face to face with a boy about his own age, dressed in blue satin and lace, on the lid of a cookie tin in his Hong Kong home. “Back in the ’50s and ’60s, cookies would come in round tin boxes, and I remember seeing Blue Boy on the lid of a cookie box,” Li recalls. “I didn’t know what to make of it.”

Cookie tins, Christmas ornaments, ashtrays, and tea towels are just a few of the knickknacks that Thomas Gainsborough’s 1770 painting has inspired. Blue Boy’s conquest of pop culture began in the 19th century but ramped up after the portrait’s well-publicized sale to Henry E. Huntington in 1921. The New York Times called it “the world’s most beautiful picture.”

An assortment of Blue Boy figurines. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The sale set off a media frenzy that would not be matched until another shaggy-haired British export—the Beatles—visited the United States in 1964. An estimated 90,000 people paid their last respects in a three-week farewell exhibition at London’s National Gallery. World War I was still a fresh wound, and, as The Huntington’s former Art Museum director Kevin Salatino mused in his forward to the book Blue Boy & Company, “it is difficult not to believe that at least part of the anguish of Blue Boy’s leave taking was its comingling in the public’s mind with the leave taking of their sons and brothers for the war, many of them never to return.”

The National Gallery’s director, Charles Holmes, famously scribbled “Au Revoir, C.H.” on the back of the painting’s stretcher in the hope that it would someday return. But it hasn’t left California since, and, until its recent conservation treatment, had not been off view for more than a few days since The Huntington opened to the public in 1928. In 2022, however, Blue Boy will retrace his steps to the National Gallery, where he’ll go on display on Jan. 25—a hundred years to the day after he left.

Visitors view Thomas Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy at The Huntington in the 1930s. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

What is it about Blue Boy that appeals to advertisers, entertainers, and interior decorators? His youth? His fancy clothes? Nostalgia? Notoriety? Over the years, he has served as a stand-in for boyhood, Britain, and fine art itself. American Anglophiles consumed Blue Boy tchotchkes the way they might consume Downton Abbey merch today.

Although Blue Boy wasn’t engraved or otherwise reproduced in Gainsborough’s lifetime, the artist’s 1785 portrait of Sarah Siddons—a celebrity actress—graced enamel patch boxes. And his bucolic 1758 landscape The Rural Lovers decorated teapots, bowls, and mugs of Wedgwood and Worcester porcelain. After his death in 1788, Gainsborough’s nephew Gainsborough Dupont—now thought to be the model for Blue Boy—published several prints of his uncle’s work in an effort to preserve his legacy, including Blue Boy in 1812.

An assortment of Blue Boy collectibles. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

By that time, the painting itself was owned by the 2nd Earl Grosvenor, who generously loaned it out and allowed the public to view it at his London residence, Grosvenor House. When Blue Boy was displayed alongside Gainsborough’s Sarah Siddons and The Honourable Mrs. Graham in Manchester in 1857, the painting was already famous. “Everyone knows the story of the Blue Boy,” The Manchester Guardian commented. But the landmark exhibition reawakened interest in Gainsborough, spawning inexpensive copies of all three paintings.

Blue Boy was usually paired with Mrs. Graham or Georgiana Spencer, Duchess of Devonshire, whose 1785 portrait by Gainsborough made news after being sold for a record price to the dealer Thomas Agnew in 1876—and then stolen from Agnew’s gallery two days later by Adam Worth, who was the inspiration for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Dr. Moriarty. (It was recovered in 1901 and bought by American financier and collector J. Pierpont Morgan, prompting another spate of headlines.) An 1884 book on fancy dress balls described Duchess of Devonshire and Blue Boy costumes, and W. P. & G. Phillips of London and Samson of Paris produced pendant porcelain figurines of the two.

Blue Boy decorations at the Huntington Store. Photo by Aric Allen.

Blue Boy’s fame may have been further fueled by the Harry Potter–like popularity of the 1886 novel Little Lord Fauntleroy, whose title character is “a graceful, childish figure in a black velvet suit, with a lace collar, and with lovelocks waving about the handsome, manly little face,” wrote author Frances Hodgson Burnett. The book’s illustrator, Reginald Birch, likely drew inspiration from Blue Boy; similarly, an 1870 book of nursery rhymes dressed “Little Boy Blue” in a cavalier’s cape and lace collar.

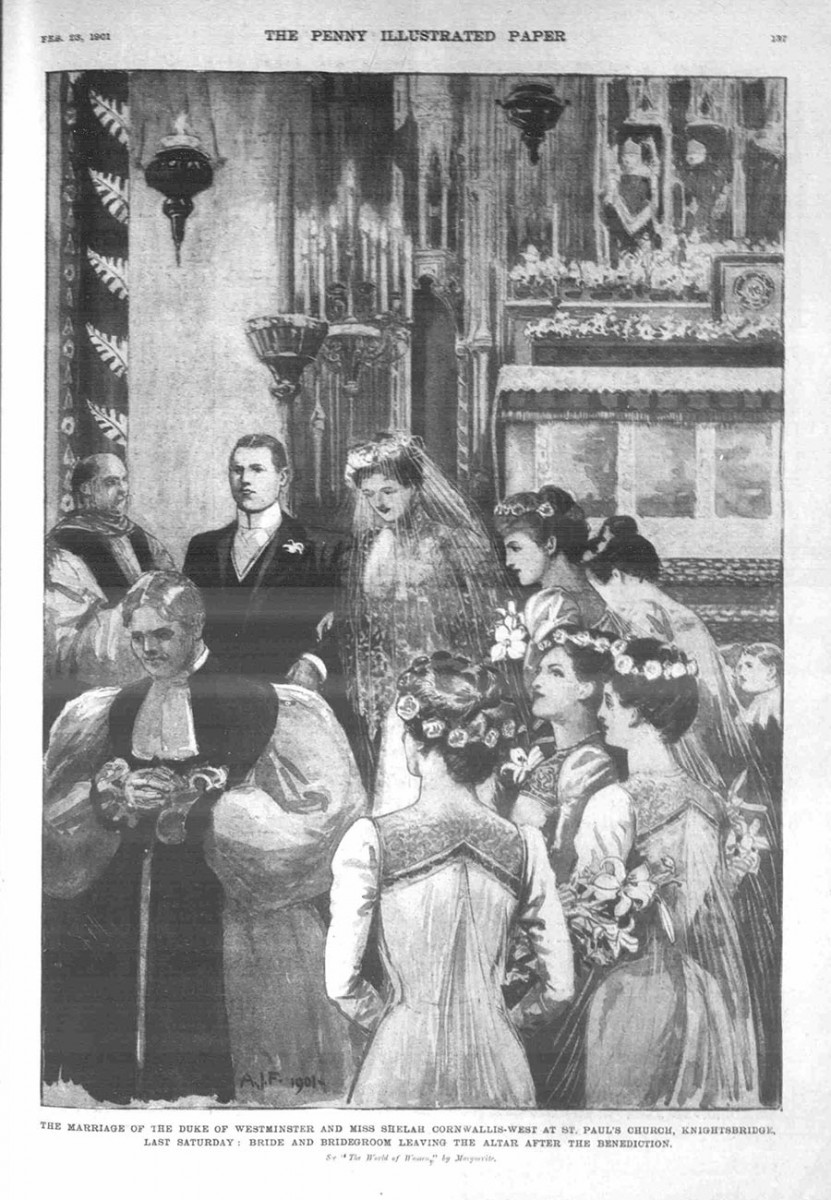

When Earl Grosvenor’s great-grandson, the Duke of Westminster, married in a lavish London society wedding in 1901, the pageboys who carried the bride’s train were dressed as Blue Boy, reported The Guardian, in “blue satin suits slashed with silver and fastened with paste buttons. … Blue velveteen cloaks were slung from their shoulders, and they had black Cavalier hats with blue ostrich feathers” and blue bows on their breeches. Twenty years later, though, the duke sold the prized painting to art dealer Joseph Duveen, along with Joshua Reynolds’ Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse. It was one of many high-profile British art sales necessitated by punishing estate taxes; much of that art went to deep-pocketed American industrialists, who traded cash for class. Melinda McCurdy, The Huntington’s curator of British art, points out that such an important painting “would definitely be stopped” from leaving the United Kingdom today, thanks to modern cultural heritage laws.

“The Marriage of the Duke of Westminster and Miss Shelah Cornwallis-West at St. Paul’s Church, Knightsbridge, Last Saturday: Bride and Bridegroom Leaving the Altar After the Benediction,” The Penny Illustrated Paper, Feb. 23, 1901. The pageboys, such as the one depicted on the far right, who carried the bride’s train were dressed as Blue Boy. Image © The British Library Board.

The international press breathlessly chronicled the portrait’s journey “from gilded galleries in Park Lane to the Wild West across the winter sea,” to quote Cole Porter’s ditty “The Blue Boy Blues.” Duveen gave Blue Boy a royal welcome, displaying the canvas in a shrine-like setting in his New York City gallery with silk velvet wall hangings, Oriental carpets, and flattering lighting before shipping it to Huntington’s California estate. By the time Blue Boy arrived in San Marino, it was more than a painting; it was an icon. The Indianapolis Star even suggested that Blue Boy’s presence “ought to keep Los Angeles on the art map long after the movie fad shall have evolved into something else and Hollywood shall be as dead as Pompeii and much more forgotten.”

Blue Boy’s departure from Britain and its arrival in America prompted a fresh wave of pop culture tributes on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1922, a blue chow named Blue Boy won best in show at the Chow Chow Club’s dog show at Madison Square Gardens. In 1925, British shoppers could collect coupons from Cadbury cocoa boxes and exchange them for a free box of Cadbury chocolates with a color reproduction of “Gainsborough’s famous painting” on the lid. Cadbury—a proudly British brand that boasted the patronage of three queens—undoubtedly hoped to capitalize on lingering sentiment surrounding the loss of Britain’s most famous son.

A Cadbury Company chocolate tin depicting Blue Boy, ca. 1920. Photo by Aric Allen.

Hollywood jumped on the Blue Boy bandwagon, too. Laurel and Hardy’s Wrong Again (1929) centers on the theft of Blue Boy, which the comedians confuse with a horse of the same name. A prize hog called Blue Boy appeared opposite Will Rogers in State Fair (1933). Marlene Dietrich was photographed in a Blue Boy costume, and Shirley Temple wore one in Curly Top (1935).

If Blue Boy was once the most famous painting in the world next to the Mona Lisa, to which it was often compared, it risked losing that title in 1927, when Huntington purchased Pinkie, Thomas Lawrence’s 1794 portrait of young Sarah Moulton. Because the two paintings are similar in size and depict children of similar ages, they became inextricably linked, though they were painted about 24 years apart and had no connection until they both ended up in San Marino. “Pinkie fits perfectly as Blue Boy’s girlfriend,” McCurdy laughs. “They’re a match made in museum heaven. But they literally have nothing to do with each other in an art historical sense.”

Clare Graham, Pinky and Blue Boy Painted Folding Screen, 1994. Photo by Kate Lain.

Pinkie would be the last British painting that Huntington purchased before his death in May 1927. (British newspapers declared: “Owner of Gainsborough’s ‘Blue Boy’ Dead.”) The following year, The Huntington opened to the public; Pinkie and Blue Boy were its unofficial mascots, and they have been paired in both the public imagination and pop culture ever since. Indeed, most Americans came to know and love Blue Boy and Pinkie through inexpensive, mass-produced reproductions, rather than direct contact with the paintings themselves.

Miniature reproduction artworks—whether color prints, figurines, faux Fabergé eggs, or porcelain plates—appealed to consumers who wanted to decorate their homes (and advertise their good taste) with Old Masters. A reproduction of Blue Boy can be spotted on a wall of the Cleaver family home in Leave It to Beaver, television’s paean to American boyhood. Crafty connoisseurs could make do-it-yourself Pinkies and Blue Boys from needlepoint kits, paint-by-numbers sets, or knitting patterns for doll clothes.

A Blue Boy figurine with the Huntington Library in the background. Photo by Aric Allen.

The pink-and-blue pair inspired dolls, drinking glasses, playing cards, socks, and Halloween costumes; they’ve appeared as tableaux at the Pageant of the Masters and on a Rose Parade float. Mr. Toad wears a familiar blue suit in his Wild Ride at Disneyland. A printed polyester shirt featured Mickey Mouse as Blue Boy and Minnie as Pinkie. In 1984, Kermit the Frog posed as “Green Boy” for Miss Piggy’s Art Masterpiece Calendar; the image has since been reproduced on posters, trading cards, and puzzles. According to Hugh Belsey—former curator of Gainsborough’s House in the artist’s native Sudbury and co-author of Gainsborough Pop—most of the earlier pop culture material, “no matter its dubious taste, was reproduced in admiration,” whereas more recent Blue Boy copies and souvenirs “have an element of tongue-in-cheek cynicism about them.”

After being mocked as effeminate by MAD Magazine and Dennis the Menace, Blue Boy became an unlikely gay icon in the 1970s, inspiring Blueboy, a gay lifestyle magazine. The debut issue featured a model dressed as Blue Boy sans breeches, his plumed hat strategically placed between his legs. Artists Robert Lambert, Howard Kottler, and Léopold Foulem embraced Blue Boy as a symbol of gay liberation. His flamboyant clothes and hair complemented the gender-bending, swashbuckling style of the New Romantics; he’s referenced in the music video for British band Visage’s 1981 single “Mind of a Toy”; and a 1986 Garbage Pail Kid trading card, “Blue-Boy George,” mashed up the painting and the androgynous Culture Club lead singer.

Actor Jamie Foxx dressed as Blue Boy in a pivotal scene of director Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained, 2012. Sony Pictures.

Hollywood, too, has rediscovered Blue Boy. Actor Jim Carrey insisted on donning a Blue Boy costume for a 1995 Esquire photo shoot, even though the magazine’s editors had already assembled a rack of clothes by contemporary menswear designers. And director Quentin Tarantino paid tribute to a now-lost German silent movie about the painting—F. W. Murnau’s 1919 Der Knabe in Blau—by putting Jamie Foxx in a frilly blue suit in a pivotal scene in his 2012 western Django Unchained. The obscure film reference doubles as an easily comprehensible visual joke, the conspicuously elegant suit contrasting with the bloody action.

While the color blue is usually associated with Democrats in America, Belsey points out that “in England, blue is the color of the Conservative Party, so we generally see Tory prime ministers dressed as the Blue Boy during their term in power.” Blue Boy entered the political fray in the United States in 2017, when MAD caricatured White House press secretary Sean Spicer as The Blue Spokes-Boy, a pompous man-child with an American flag pin on his blue satin lapel.

Left: Kehinde Wiley, A Portrait of a Young Gentleman, 2021. Oil on linen, canvas: 70 1/2 × 49 1/8 in. (179.1 × 124.8 cm.), frame: 87 × 64 × 5 1/4 in. (221 × 162.6 × 13.3 cm.) © Kehinde Wiley. Collection of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, and commissioned through Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Right: Thomas Gainsborough, The Blue Boy, ca. 1770. Post-conservation photo by Christina Milton O’Connell. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Will the publicity surrounding his National Gallery homecoming—and Kehinde Wiley’s recent portrait in response to the great Gainsborough painting—amp up Blue Boy mania? If so, it’s unlikely to take the form of ashtrays and teapots; think memes, TikTok challenges, ironic action figures, and Pez dispensers instead.

To read more about The Blue Boy, preorder the book Kehinde Wiley: A Portrait of a Young Gentleman from the Huntington Store.

You can also preorder Gainsborough’s Blue Boy.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell is a freelance writer based in Glendale, California.