The Bogey Man

Posted on Thu., April 21, 2016 by

Life, Learning, Leadership, and Legacy according to Steve Koblik

Steve Koblik, in 2009, seated in his office at The Huntington, where he has served as president since 2001. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

"OK, give me a number. And then once you do that, I'll figure out the bogey." This is Steve Koblik. He's asking for an estimate of how much a certain project will cost. It could be the amount needed to refurbish the Huntington Art Gallery, or to finish the Chinese Garden, or to revamp the Huntington's vast irrigation system. It's the number against which he'll consider a range of factors—whether he thinks the project's worth it; whether he can raise the money; whether he can get that number down to a level he finds more palatable.

Koblik often peppers his speech with sports metaphors (bogey is a golf term, although in this case, he's using it loosely). "OK, sports fans. Here we go. This is important." That's how he sometimes addresses his senior staff group at one of its raucous Tuesday morning meetings.

He's the consummate coach, always guiding his team to perform at the top of their game. And his coaching isn't limited to his direct reports. He happily engages everyone he meets with an intense yet friendly mentoring style, from vice president to security officer, curator, donor, prospective donor, post doc, or tenured professor. "He's got the type of charisma that instantly brings people close," says Stewart Smith, the Huntington's chair of the Board of Trustees. You just so desperately want to be on his team. So much so, that Koblik has succeeded in raising more than $700 million in support of his cause: to further enhance one of the most significant collections-based research and educational institutions in the world.

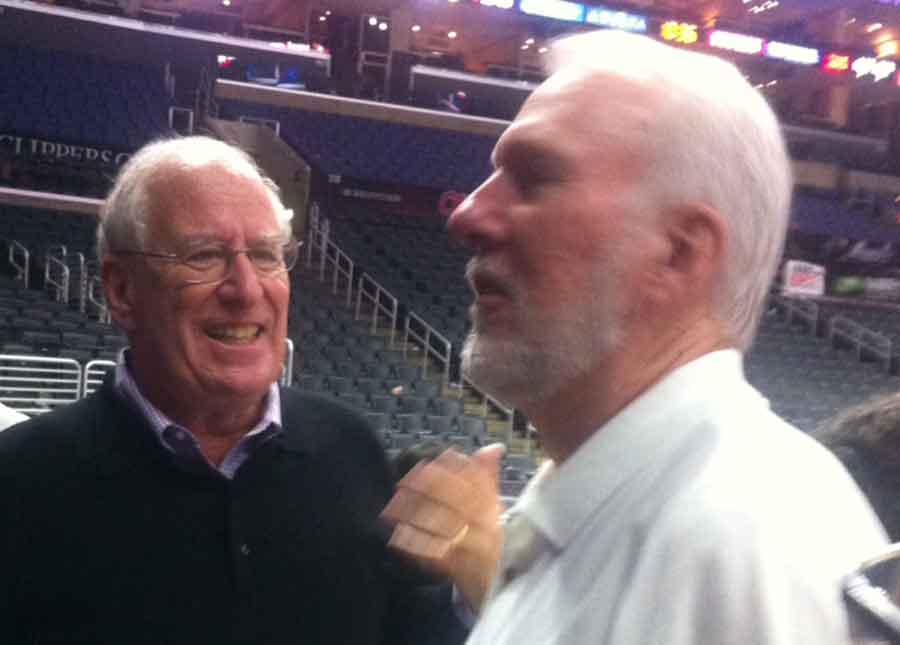

An avid golfer today, Koblik comes from a wide-ranging athletic background. At UC Berkeley, he played 16 intramural sports, "including ping pong," he quips. Everybody at Kappa Nu—the nerdy fraternity—had a job. Says Koblik, "Mine was to be the resident jock." As a history professor at Pomona College, he was tapped in 1979 to work with newly named basketball coach Gregg Popovich to provide academic assistance to the men's basketball team. "Steve monitored their grades and made sure each one of them was doing all right," says Popovich. "He took it very seriously. His judgment was really very important. He could help me figure out if a particular recruit was really up for the rigors of college life. Or, if I had my doubts about somebody, he might say, 'I think this kid's got great character; I think he can do this; we can help him through.'"

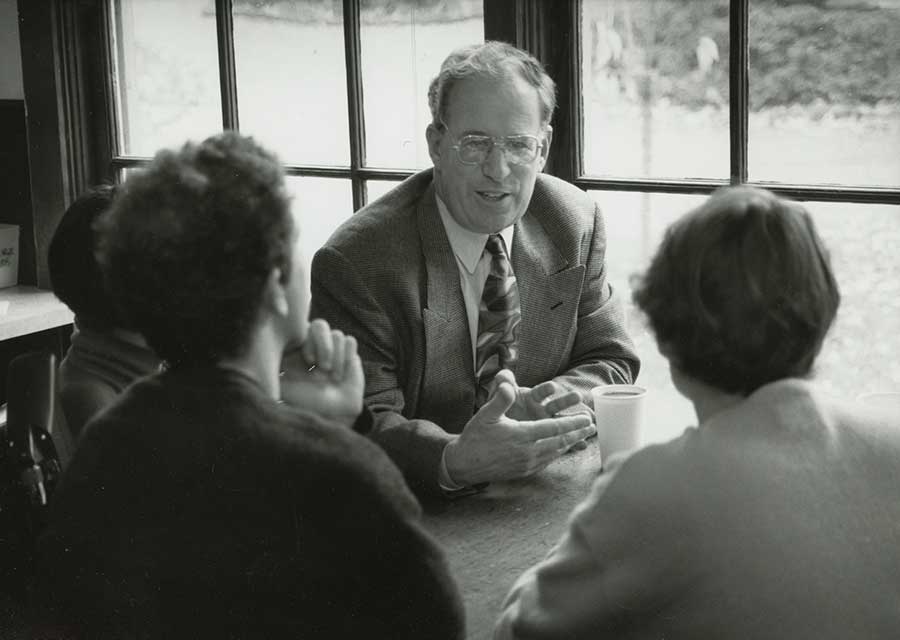

Koblik, in 1995, talking with students at Reed College, where he was president from 1992 to 2001. Photograph courtesy of Special Collections, Eric V. Hauser Memorial Library, Reed College.

They remain close friends. Popovich, of course, has gone on to become the renowned coach of the San Antonio Spurs. He says: "One of the things I love most about Steve is his sense of humor. He would send emails after some of the [Spurs] games, evaluating different plays, what we could have done better, or what he thought we did well. He would throw in everything—I liked what you guys did there; I wish you'd tried this; it was always funny—total satire—he'd say sarcastic things about the league, then add something about marketing, economics, and the politics of it. It was funny, but he always nailed it. It was very much in line with what we had done in evaluating the game ourselves." Popovich and Koblik have a fun-loving friendship with deep intellectual roots: Koblik, the European historian; "Pop," as he is known, the Russian scholar. But Popovich also recognizes Koblik's tremendous capacity for compassion: "He has a huge heart. He'd check in with me after a game and say, 'Hey—something's up. I see it in your face, or I heard something in your voice.' He's remarkably insightful, really feels for people. When you have his work ethic combined with his level of caring—it's unique."

Koblik worked alongside Popovich for nine years. "He was intense, tough, focused, demanding," remembers Koblik. He also showed a deep loyalty to his players. All of this impressed him deeply and began to feed into Koblik's own brand of coaching. He admits to being demanding and setting high expectations: "But I don't micromanage. What I try to do is play to people's strengths, get them to leverage what they do best. Give them breathing space. And also allow them to fail."

Koblik's Pomona years as a teacher are legendary, says Joe Palca, science correspondent for NPR and a former Koblik student. "Steve made students do a deep dive into the subjects he taught. For a course on the origins of World War I, he sent us to the library to read the cable traffic between embassies as the war was starting."

Students knew he expected them to push hard. "And if failure occurred," Koblik says, "it was my job not to take them off the floor or the field, but to encourage them to learn from their failure." He was a notoriously tough grader. But, when he asked students to grade their own work, it turned out that they were tougher on themselves than he was.

Koblik talks with Mikki Heydorff, volunteer programs manager for The Huntington. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

IT WAS ABOUT COACHING STUDENTS then; it's about coaching everyone around him now. What's happened at The Huntington during his time as president has been nothing short of a complete transformation. The institution is on vastly improved footing financially, with expanded programs, new gardens, pristine facilities, and the prospects for a productive, vital future.

Says Stewart Smith: "I tell people that Steve's the kind of leader that goes from mountaintop to mountaintop. It's invigorating just trying to stay on the same horse with the guy."

When he took the job in 2001, Koblik inherited a renowned institution with a history of fiscal instability. The search committee that interviewed him let on that his first order of business would be to get the institution's finances in order. "It wasn't the most exciting thing to do, but he was enthusiastic about it, he got people on board, coaxing and coaching," says Smith. "He was highly qualified to do the job—we knew that. But we didn't really know about his ability to bring people along and to build camaraderie in the way that he did. People quickly wanted to hitch their wagons to him."

Koblik's mantra right out of the gate was fiscal discipline. He says: "We froze salaries, began raising considerably more money, and at the same time, we were incredibly transparent. And if staff or anyone, really, wondered why things were so tough, and why times were so lean, they had the information right at their fingertips. No secrets."

It was simple: The Huntington had been spending more than it was bringing in—a common problem for many a cultural institution. With no regular government subsidy and an endowment of about a third the size needed to run the place adequately, Koblik had his work cut out for him.

Professor Koblik in a Pomona College classroom in 1983. Photograph courtesy of Pomona College Archives.

"Ultimately," says former Chief Financial Officer Alison Sowden, "it came down to Steve's showing great respect for staff at all levels of the institution. And they responded with loyalty and enthusiasm to one of the greatest institutional leaders I have ever been privileged to know." Sowden is now CFO at the Art Institute of Chicago and the school there. "He's been a model and mentor for me in my own career," she says.

He's also stunningly self-deprecating, constantly poking fun at himself. Famously bad at remembering names and a regular with malapropisms (is that prostate or prostrate?), he keeps the staff, volunteers, and governing boards in stitches. In the lineup of presidential portraits along the wall outside of his office, his picture is missing, and in its place hangs one of Bozo the Clown. "This is, in part, about having fun. If we're not having fun at work, then really, what's the point?" he says.

When he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, he quipped that the real thrill of making the list was being in the company of one of his lifelong heroes—Mel Brooks. He and Brooks were elected in the class of 2012. Other class members: Hillary Clinton, Sir Paul McCartney, and Melinda Gates.

With Koblik's broad appeal, he set out to coach a series of winning seasons, even while the economy began to falter and slide sideways.

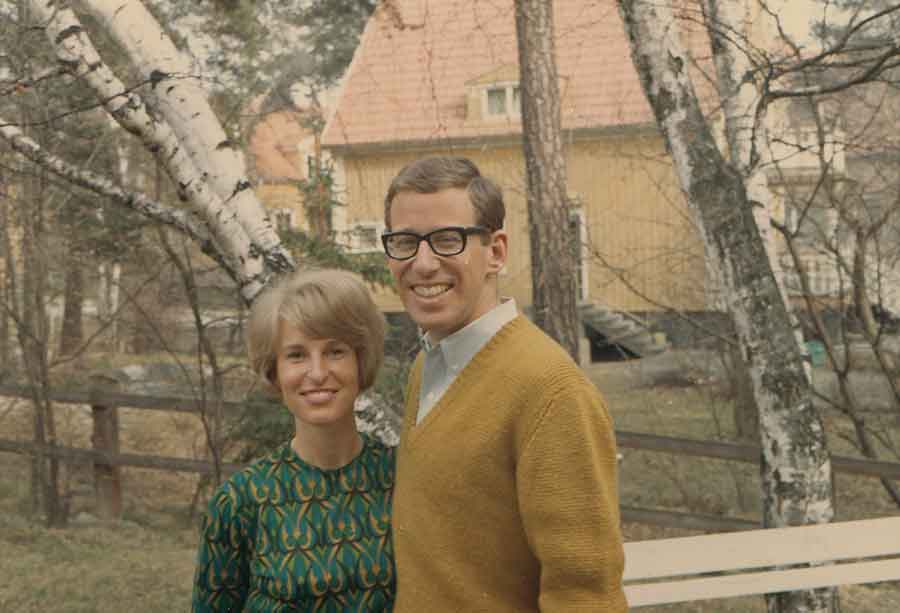

Koblik and Kerstin in Stockholm, Sweden, 1967.

"Even in the toughest of times, the culture here has been incredibly humane," says Laurie Sowd, vice president for operations. "And that comes directly from Steve. He's fair-minded and loyal and supportive. Everything emanates from that."

His favorite movie? The Sound of Music.

Coming in at a close second: The Producers.

Makes total sense.

KOBLIK SET HIS SIGHTS ON THE HUNTINGTON DECADES AGO.

He was born and raised in Sacramento. His father was an architect; his mother, a homemaker, had been a self-proclaimed flapper in the 1920s—fun-loving, high-spirited, bathtub gin drinking, always in search of adventure, says her only son. That could well explain his indefatigable nature. (He credits his daily naps.)

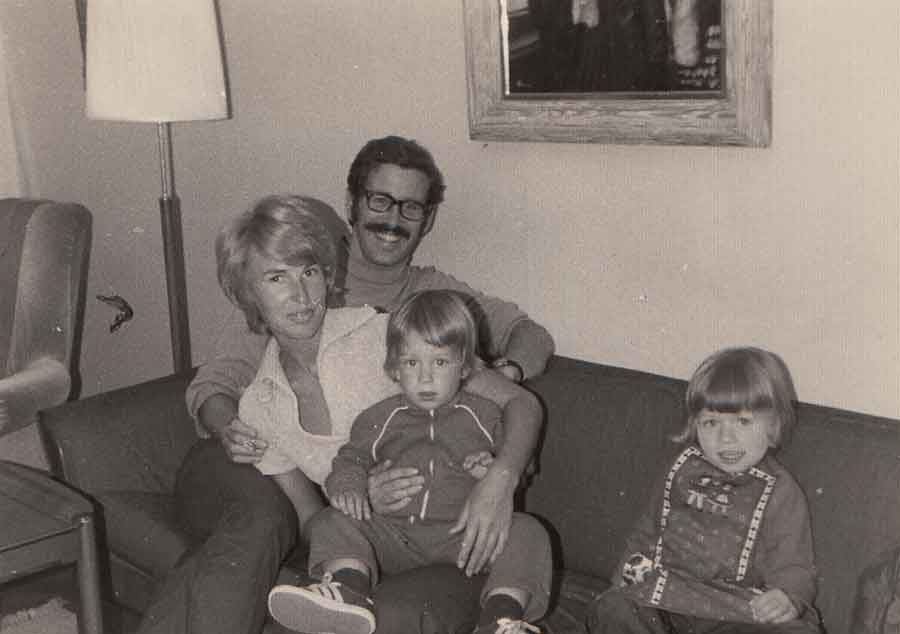

He earned his undergraduate degree at UC Berkeley, got his master's at University of Stockholm, and holds a Ph.D. from Northwestern. As a graduate student, he homed in on Sweden's role in World War II and focused his dissertation there; later, he dug into Sweden's role in the Holocaust and wrote a highly acclaimed book on the topic: The Stones Cry Out. It was in Sweden that he met his future wife, Kerstin Olseni. They have been married 47 years and have two children and four grandchildren.

After living on and off for nine years in Sweden, he returned to Southern California to teach at Pomona. And over time, he became deeply familiar with, and a bit obsessed by, The Huntington.

Koblik with his wife, Kerstin, and their two children in 1971.

"In the '60s, I walked through the doors of the Library with bushy hair and a mustache, wearing clogs. And they took one look at me and said, 'Steve, you're a nice guy. But we don't let people like you in this place.'" A bit of a bohemian by looks, he was nevertheless a serious scholar, interested in the history of Southern California and wanting to do some research on Henry Huntington himself. The closed atmosphere—one that suggested clubbiness and exclusivity—irked him. He wouldn't let it go.

He remembers telling friends, "I'd like to be president of The Huntington one day."

In the meantime, he won one teaching prize after another at Pomona, became dean of the faculty at Scripps, and then went on to take the helm at Reed College in Portland, Ore. He held the presidency there for nine years.

And then, by a remarkable confluence of events, The Huntington presidency opened up, and Koblik was in perfect position for the job.

HE MOVED FROM REED TO THE HUNTINGTON in the fall of 2001. Sept. 11, in fact, was the day of Koblik's first board meeting. One might have seen this as a really bad omen, but Koblik saw it as a time for strength and courage, and a time to pull together in the wake of the terrorist acts. So instead of closing The Huntington for the day and sending people home, he kept the gates open and watched as visitors came by the dozens, then the hundreds—searching for solace, for comfort, for meaning.

It is the essence of the place, and something Koblik realizes deeply. It's sometimes hard to articulate exactly what The Huntington does for people. It doesn't cure cancer; it isn't in the business of providing meals to the homeless; it doesn't take in stray animals; it's not the kind of nonprofit that pulls at one's heartstrings the way the Red Cross does. It's not trying to be that. And it's not like a college or university in the conventional sense, even though it is involved in research and education. But, it does not award degrees; it has no alumni. So it can be a little challenging to articulate what brings people to The Huntington and fuels their passion and commitment to the place.

Koblik with Gregg Popovich, coach of the San Antonio Spurs. Photograph by David S. Zeidberg.

Koblik explains his own passion for it in this way: "The Huntington is the keeper of the flame. We collect and preserve culture, and we celebrate human achievement, and that is fundamental if you want to know who we are as a people and where we might be going." The Huntington's collections explain so much about how the United States came to be—warts and all—with historical, literary, and artistic documentation that speaks to the early formulations of the rule of law (think Magna Carta); the Founding Fathers, slavery and the Civil War, the mission period and Native Americans, expedition and discovery, railroads, women's suffrage, immigration, exclusion, innovation and invention, exploitation and emancipation. And the breadth and depth of The Huntington's collections is simply astonishing: from micro to macro. Here is a library with nine million items, and a European and American art collection that spans six centuries. And all this is set among beautiful, world-renowned botanical gardens with 15,000 species, many of them rare and endangered.

Back when Koblik was organizing The Huntington's first comprehensive fundraising campaign, the renowned AIDS researcher David Ho said, "We give people life. You give people meaning in life."

THE AFTERNOON BEFORE KOBLIK'S FIRST DAY ON THE JOB, he walked over to the mausoleum, the gravesite of Henry and Arabella Huntington. "He wanted some quiet time there," says Kerstin. "He had said he wanted to think deeply about what Henry Huntington might do, and how he would want the institution run."

In some respects, Koblik's game has been a collaboration, in part, with Henry Huntington himself—constantly thinking about what the founder's intentions might have been and whether Koblik's decisions and the institution's direction have lined up with those intentions. But the collaborative spirit goes deeper and wider than that—with area institutions, disparate groups of donors, his boards, the staff. "Together," he says, "we did this."

"He can come on strong, totally take over a room," says one staff member. "But he's also one of the softest, most compassionate people I've ever met. At one particularly low point for me, he had some spot-on advice. He said, 'It's not what you get in life; it's what you do with what you get.' It changed my entire perspective. And I will miss him terribly."

Meanwhile, Gregg Popovich has something on his mind, touched in a very different way by Koblik's retirement. "I'm just afraid Steve's going to show up on my doorstep, looking for a job!"

Susan Turner-Lowe is vice president for communications and marketing at The Huntington.