Posted on Fri., April 24, 2015 by

The Huntington's curator of photographs captures the emotional impact of the Civil War

![Veterans with John B. Bachelder [standing] at the 29th Ohio Infantry Monument, Gettysburg, ca. 1887. Unidentified photographer. Veterans with John B. Bachelder [standing] at the 29th Ohio Infantry Monument, Gettysburg, ca. 1887. Unidentified photographer.](/sites/default/files/broken_1.jpg)

Veterans with John B. Bachelder [standing] at the 29th Ohio Infantry Monument, Gettysburg, ca. 1887. Unidentified photographer. Jennifer Watts writes: "Gettysburg became the obsession of the artist John B. Bachelder (1825-1894)...At battle's end, Bachelder visited fields, farms, and hospitals to collect eyewitness testimonies and establish precise troop positions. He spent the next 30 years gathering soldier's recollections, writing a congressionally funded eight-volume history, and supervising the placement of monuments on the battlefield. More than anyone other than Lincoln himself, Bachelder ensured that Gettysburg would loom largest in Civil War myth and memory."

If you missed The Huntington's unprecedented exhibition of 200 rare Civil War photographs in 2013, you will be pleased to learn that the Huntington Library Press has just published a powerful book based on the show—A Strange and Fearful Interest: Death, Mourning, and Memory in the American Civil War. Author Jennifer Watts, curator of photographs for The Huntington, explores the toll the war took on the nation's psyche, providing thoughtful and moving context to the work of such famous war photographers as Mathew Brady, Timothy O'Sullivan, George Barnard, Alexander Gardner, and Andrew J. Russell, among others.

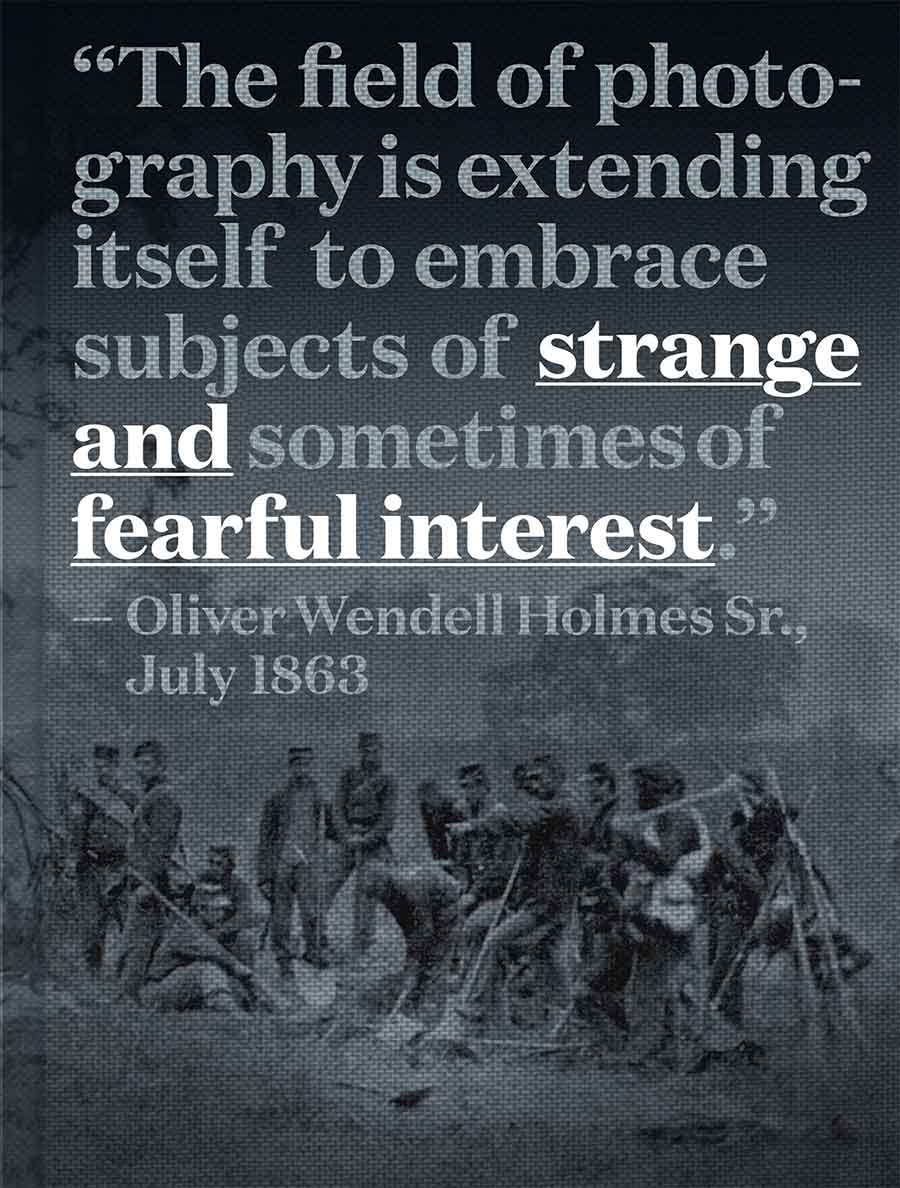

The book takes its title from a statement made in 1863 by the physician, poet, and professor Oliver Wendell Holmes regarding images of Antietam, where his son, a future U.S. Supreme Court justice, was wounded in one of the bloodiest battles of the war: "The field of photography is extending itself to embrace subjects of strange and sometimes of fearful interest." The war coincided with the rise of photographic and printing technologies that enabled the dissemination of war imagery to the homes of ordinary Americans and profoundly affected their experience of the conflict.

Watts first began work on the exhibition in 2008, when she and her fellow curators at The Huntington were planning exhibits in anticipation of the sesquicentennial of the outbreak of the Civil War.

At around the time that Watts was conceiving the exhibition, Drew Gilpin Faust, president of Harvard University, came to The Huntington to give a lecture on This Republic of Suffering, her acclaimed book about how the nation's understanding of death was affected by the high number of casualties during the Civil War.

Portrait of a Union Soldier, Chattanooga, Tennessee, ca. 1863-64, by Isaac H. Bonsall (1833-1909), as seen during the Civil War photographs exhibition at The Huntington's MaryLou and George Boone Gallery in 2013.

"She spoke about what the war meant for women," Watts recalls. "She discussed the omnipresence of death in women's diaries and rising casualty counts. She said that roughly 3 percent of the population of the United States died—or what would be today's equivalent of 7 million people. Many men left home and never came back, and their families did not know where they were."

There was no infrastructure at the beginning of the war to deal with the massive carnage. Bodies were often left to rot unburied on battlefields. Before the Civil War, most people had died at home, tended by their loved ones. The impact of knowing that many young men had died in their 20s among strangers and could not be located struck a terrible blow to those they left behind.

"As a mother, wife, and sister, I found her talk very moving," says Watts. "From that night forward, I knew I wanted the exhibit to focus on death, mourning, and memory. I also decided to limit it to items drawn only from The Huntington's collections." The book preserves the show's threefold focus and reproduces indelible images in The Huntington's collections.

Henry Huntington was a boy of 15 when the Civil War broke out, and like many people of his generation, he was fascinated by the war. He later amassed one of the greatest Civil War collections in existence, primarily by purchasing several of the largest and most notable collections of others, including the Judd Stewart collection of Lincoln materials.

Battlefront photographs featured in the book include Alexander Gardner's views of the dead at Antietam; rare photographs from Andrew J. Russell's U.S. Military Railroad Album, which include haunting scenes of battlefield devastation and newly established military cemeteries; and George Barnard's album Photographic Views of Sherman's Campaign (1865–66).

Cover of Jennifer Watt's book, published by the Huntington Library Press.

In a chapter devoted to the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, readers encounter a rare "Wanted" poster seeking the capture of John Wilkes Booth and his accomplices, and mementos of grief, such as a Lincoln mourning ribbon, as well as lithographs of Lincoln deathbed scenes and photographs of the large public displays of mourning associated with his funeral. There is even a set of stark photographs by Alexander Gardner depicting the execution of the Lincoln conspirators.

Watts also provides a chapter on the commemoration of the war, which includes images drawn from John P. Nicholson's collection related to the establishment of the Gettysburg National Monument. In addition, there are images preserved by Civil War veteran and Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper illustrator James E. Taylor, whose scrapbooks included exceptionally rare battlefield and convalescent photographs.

The book includes a complete checklist and thumbnail images of all the items that appeared in the exhibit, as well as elements created since the exhibit closed. One of these is a fascinating interview by Watts of Barret Oliver, an artist who employs Civil War–era photographic and darkroom techniques. For the exhibition, he worked with film artist Kate Lain, new media developer at The Huntington's Office of Communications and Marketing, to create In the Usual Manner, a short film that provides viewers with a window into the intricate and laborious photographic processes used in the 19th century. In the interview, Oliver shares his insights into the challenges that pioneering photographers faced working in the field with cumbersome equipment and delicate glass plates.

Watts also includes a "score" by artist Steve Roden that diagrams an original sound work for the exhibition that he created in response to battlefield images of Antietam. Roden's sonic palette—composed of antique instruments, crickets, birds, and interludes of silence—invokes an aural space in which to contemplate the deep pain and persistent natural beauty of the site. (The film In the Usual Manner is available online, and an excerpt from Roden's sound work can be found here.)

Reflecting on the aftermath of the bloodshed near the end of the book, Watts writes: "What are we to make of the American Civil War in our 21st-century world? Historians continue to have their say. Documentarians, writers, pundits, and reenactors do, too. Even so, there is often a troubling disconnect between the head and the heart in confronting such incomprehensible loss. Photographs provide documentation and clues, but as [an] unknown sage reminds us, they are ciphers at best... 'All of this desolation imagination must paint—broken hearts cannot be photographed.'"

Kevin Durkin is editor of Huntington Frontiers and managing editor at The Huntington's Office of Communications and Marketing.