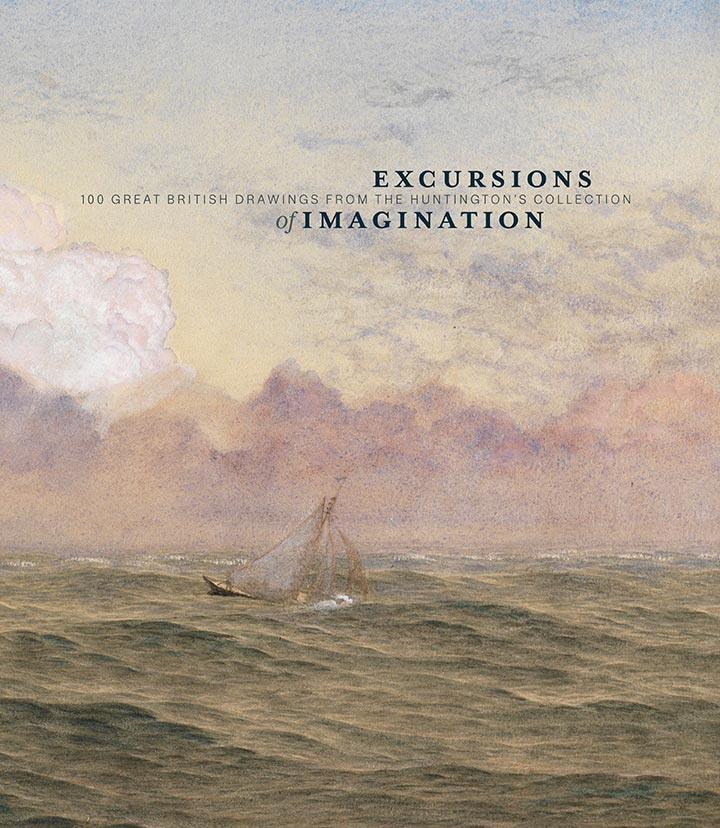

Excursions of Imagination

Posted on Tue., July 12, 2022 by

Excursions of Imagination: 100 Great British Drawings from The Huntington’s Collection examines for the first time the strength and diversity of The Huntington’s British drawings collection. The catalog is available from the Huntington Store.

“100 Great British Drawings,” a major exhibition at The Huntington, traces the practice of drawing in Britain from the 17th through the mid-20th century, spotlighting The Huntington’s important collection of more than 12,000 works that represent the great masters of the medium. On view through Sept. 5, 2022, in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery, the exhibition features rarely seen treasures, including works by William Blake, John Constable, Thomas Gainsborough, and J. M. W. Turner, as well as examples by artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and early 20th-century modernism. A fully illustrated catalog, Excursions of Imagination: 100 Great British Drawings from The Huntington’s Collection, accompanies the exhibition, examining for the first time the strength and diversity of The Huntington’s British drawings collection, a significant portion of which has never been published before. The Huntington is the sole venue for the exhibition. The following excerpt is from the catalog’s title essay, “Excursions of Imagination,” by Ann Bermingham, professor emeritus of the history of art and architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Stretching from the 17th to the 20th century, the range of drawings and watercolors in this volume testifies not only to the richness of The Huntington’s acquisitions but also to the breadth of British graphic art. Examples of portraiture, landscape, still life, botanical illustration, topography, caricature, narrative, and historical subjects all point to British artists’ extensive engagement with drawing and to its scope as a medium.

Drawing is as much a process of linear exploration as it is a record of an artist’s vision. In this sense, a drawing is a journey, an excursion of imagination. Drawing is also a kind of unmasking. Whereas oil painting, sculpture, and architecture present us with results that largely obscure the means through which they were attained, drawing invites us to discover the processes used to produce the image.

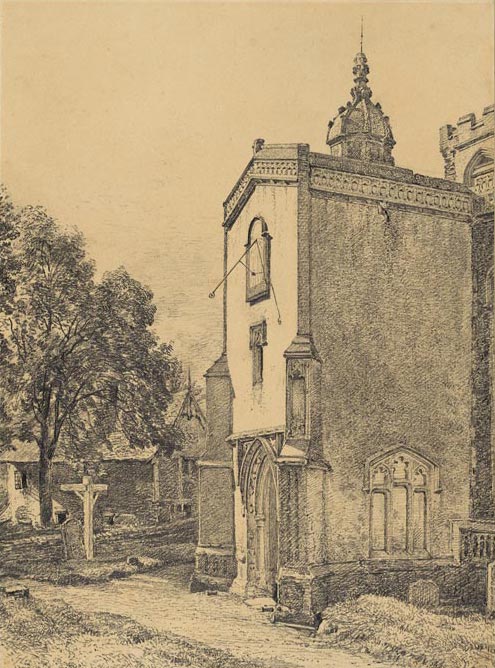

John Constable (1776–1837), East Bergholt Church and Village, undated, ca. 1817. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Drawing’s invitation to explore and understand the artist’s method makes it the most intimate of arts. As the literal trace of the artist’s hand, drawing bids us to judge the creator’s mood and disposition. We are led to think that we can read something of the artist in the drawing, just as a graphologist believes she can read the personality of the writer in her handwriting. In drawing, the artist’s temperament seems as much a part of the image as the scene or object being represented. To paraphrase the French critic and novelist Émile Zola, a drawing re-creates the world through a temperament.

Looking at a drawing raises a series of questions about the formal choices made by the artist about medium, format, touch, composition, and genre. Why the choice of pencil or chalk? Why a vertical composition instead of a horizontal one? Why a tentative outline as opposed to a bolder one? Why a particular subject and not another? These questions focus our attention on the creative process, on what would be different if the artist had not made certain choices, and how the choices she did make add to the whole.

For example, John Constable’s study East Bergholt Church and Village (undated, ca. 1817) depicts the south porch of the artist’s local parish church, St. Mary Virgin, in brilliant sunshine. Constable’s medium is graphite, a lead that, unlike ink or even chalk, provides an infinite variety of tones and lines that can be controlled through manual pressure. Given Constable’s focus on light and the architectural details of the church, graphite proved to be the perfect medium. It could be sharpened to a fine point for delicate outlines and shading or used with a broad tip to create an emphatic dark line. Examples of this variation of thickness appear throughout the drawing, both in the strong delineation of the forms and in their sensitive modeling. The vertical orientation turns the drawing into a portrait of the porch rather than a view of the whole south side of the building and its surrounding churchyard, which a horizontal format would likely have produced. Constable’s attention to light as it plays over the fabric of the church, revealing picturesque Gothic moldings, gives this drawing visual interest and a remarkable crispness. The shadowed walls contrast sharply with the porch’s facade, illuminated by bright southern light. The sundial indicates that the time is about 2 p.m. The season is high summer. The visual prominence of the sundial on the southern wall has to do with the fact that it projects outward from the plane and that some of the sharpest contrasts of tone can be found on it. According to historical records, the sundial was inscribed, “Ut umbra sic vita” (As a shadow, so is life), a reminder of mortality, of the fact that, like the shadow marching across the dial’s face, we, too, pass away. Hence, Constable’s study of light in this context hints at a meditation on life’s transience and impermanence. His formal choices accentuate the sundial and its melancholy truth. Depicting the church at another time, in other weather, or from another angle would have changed not only the character of the drawing but also its connotations.

George Romney (1734–1802), Cimon and Iphigenia, undated, early 1780s. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In this sense, a drawing asks us to empathize with the artist by entering into both the artist’s vision and the artist’s efforts to realize that vision on paper. Doing this, we share in the creative process. We become transported, partaking in the moment when one decision is made instead of another, when one option is explored and others are not. I can think of no other visual art that does that.

Studying a drawing in this way is like overhearing a conversation between the artist and herself, a discussion perhaps of possibilities or a querying of appearances. A drawing can be a declamatory statement of fact or a modestly advanced speculation, a bitter meditation or a sudden, excited exclamation. All kinds of internal conversations are possible, but often enough, artists gravitate to just a few. Their drawing styles reveal their obsessions, their tendencies toward repetition, their stubborn insistence on seeing things a certain way, their expressions of awe, their concern with truth.

In addition to providing a window into the process of creation, a drawing is a material object. Drawings are meant to be hung on a wall, tucked into a box or portfolio, or crumpled up and tossed away. Paper is fundamental to drawing’s objecthood. In Europe, the practice of drawing started in the early 15th century with the widespread manufacture and use of paper. By the late 16th century, drawing had become a basic part of the curriculum in the studios and academies on the Continent, where its purpose was to train artists to render in two dimensions the three-dimensional world. At the same time, artists and a few connoisseurs had begun to treasure drawings of the masters. By the 17th century there was a robust international trade in old master drawings, and by the 18th century drawings appeared in public exhibitions, where they were bought and collected.

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788), Diana and Actaeon, undated, 1784–86. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The art of drawing was established in Britain in the second half of the 17th century with the influx of foreign artists trained in the medium. Drawing’s late start there reflects the nation’s slow development of art institutions. Before the Royal Academy of Arts was founded in 1768, artistic training took place in private studios and small academies headed by professional artists. In these settings, students began their studies by copying prints and drawings before moving on to drawing sculpture and finally the living model. Young artists were taught to imitate a range of drawing styles of Continental masters by copying examples of their work, either prints or drawings. They were also instructed to study and sometimes copy the work of their teachers. If they were lucky, they might be allowed to study in private collections.

But perhaps the most important source of art education for British artists was travel abroad to view and copy the works of contemporary artists and old masters. James Barry traveled to Paris and then to Rome, where he stayed for three years studying ancient art and that of the High Renaissance. George Romney visited Paris, Lyon, Marseilles, and Nice before moving on to Italy. After touring Florence and Pisa, Romney spent eighteen months in Rome studying the work of Raphael. The Scottish artist Allan Ramsay traveled through Italy and settled in Naples, where he worked for three years under Francesco Solimena. Late in his career, Thomas Gainsborough, who appears to have never ventured out of England before, visited Antwerp and the Low Countries. As foreign-born artists, Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg and Henry Fuseli had decided advantages; Loutherbourg benefited from formal training at the Académie Royale in Paris, whereas Fuseli was able to travel extensively throughout the Continent before settling in Italy for eight years.

David Cox the elder (1783–1859), Paris; Rue Vivienne, 1829. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The importance of exposure to Continental art and to art of the past in the 18th century cannot be overemphasized. It provided British artists with examples of painting and draftsmanship that surpassed anything they might have found in what was still the artistic backwater of London. Continental art motivated British artists to experiment with materials, styles, and subject matter. Though portraiture dominated the British art scene at home, history painting—that is to say, subject matter derived from history, scripture, mythology, and literature—could be found throughout the Continent and was the kind of painting favored by the old masters. In academic theory, history painting’s appeal to the mind rather than simply to the eye placed it on the level of poetry. In Britain, esteem for history painting was promulgated by Sir Joshua Reynolds in his Discourses to the students of the Royal Academy.

The Academy’s commitment to history painting meant that many British artists, like Reynolds himself, found themselves torn between pursuing portraiture, which would pay the bills, and history painting, which would not. This tension is palpable in several of the drawings in The Huntington’s collection. George Romney, for instance, returned home from his Continental travels to become a popular portrait painter. His drawings, however, reveal an artist whose imagination was intensely stimulated by antiquity and the stories and characters from Greek, Latin, and Renaissance poetry. His drawing of Cimon and Iphigenia (undated, early 1780s) from Boccaccio’s Decameron is filled with a passionate energy conveyed through sweeping strokes of ink. His sketch of Circe (late 1770s or early 1780s) from Homer’s Odyssey is similar in its emphasis on dramatic gesture rather than facial expression. Romney’s example suggests that one of the roles drawing played was as an outlet for design ideas that were not always practical to realize in paint, since in Britain, history painting had little commercial value.

Thomas Shotter Boys (1803–1874), French Port Scene, undated, mid-1820s or early 1830s. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Gainsborough’s visit to Antwerp in 1783 marked a turning point in his art. While still practicing as a portraitist and landscape artist, Gainsborough began experimenting with history painting. The sketch Diana and Actaeon (undated, 1784–86) is one of three that Gainsborough made to work out the composition for an oil painting. Through a dense tapestry of white-chalk highlights and black-ink brushstrokes, we see Diana and her attendants bathing and surprised by the hunter Actaeon. The goddess flicks a handful of water at him, transforming him into a stag to be torn apart by his hounds. The sketch bears a compositional resemblance to a large oil painting that was left unfinished at Gainsborough’s death in 1788. The fact that the setting is out-of-doors allowed Gainsborough to indulge his love of landscape. The subject had been treated by Titian, and it is possible that Gainsborough may have seen Titian’s version in Paris on his trip to Antwerp. Or, he may have been inspired by the many classical scenes painted by Peter Paul Rubens, which he would have seen in Antwerp. Whatever the case may be, it is clear that the trip abroad made a deep impression on the artist, challenging him to expand his image repertoire.

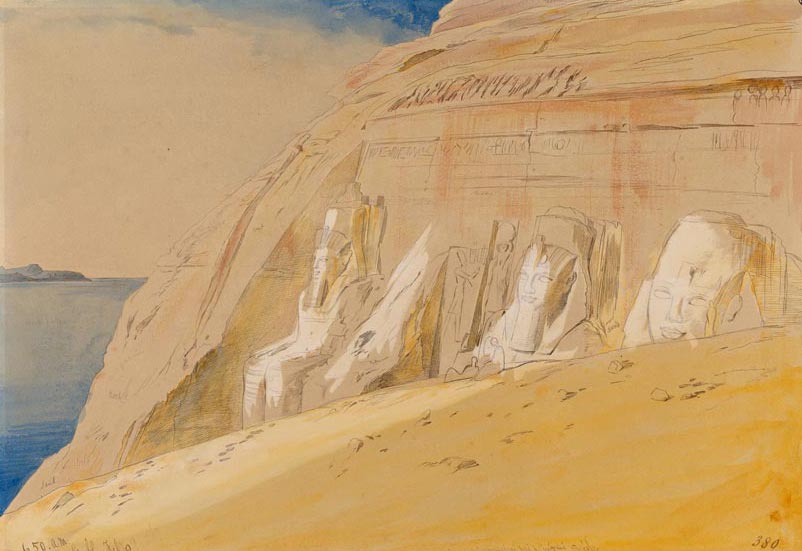

Travel for British artists was impeded by frequent wars with France, the last stretching from 1797 to 1815, with a brief intermission in 1802. After the peace that followed Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, British artists were once again able to travel the Continent freely. David Cox’s Paris; Rue Vivienne (1829), Thomas Shotter Boys’s French Port Scene (undated, mid-1820s or early 1830s), and William James Müller’s Church of St. Nicholas, Rhodes (1844) exemplify the delight artists took in European cities, with their narrow, picturesque streets, and in the old wharves that marked the rivers and coasts. By the end of the 19th century, artists were traveling further afield to places like Egypt and the Holy Land. Edward Lear’s drawings of Egypt, often created to be reproduced as prints, are particularly dramatic in their dizzying perspective views of cliffs, chasms, and antiquities. His work, like David Roberts’s Mosque of Sultan al-Ghûri, Cairo (undated, ca. 1839), speaks to Victorian Britain’s imperial reach by the middle of the century.

Edward Lear (1812–1888), Abou Simbl, 1867 (color washes added later). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

If an artist did not have the benefit of foreign travel and schooling, the next best thing was to amass a collection of prints and drawings for study. Jonathan Richardson the elder was perhaps the first English artist and connoisseur to collect old master drawings, and other British artists followed his example. Long after graduating from William Shipley’s drawing school in London, the miniaturist Richard Cosway continued to train himself in drawing by copying old master prints and drawings from his own extensive collection. His delicate graphite study of two heads (undated, ca. 1790–1800?) reveals his grasp of northern Italian Renaissance drawings by Correggio and Parmigianino.

Though William Blake would certainly have denied that copying the art of others was the source of his inspiration, he nonetheless profited from the study of drawings and prints. His work as a printmaker exposed him to a wide range of graphic art. The contemporary work of John Flaxman, James Barry, and Henry Fuseli and the reproductions of Renaissance works by Michelangelo and Raphael were all powerful influences. Blake’s illustration of a scene from Milton’s Paradise Lost—Satan, Sin, and Death (undated, 1806–8)—shows his debt to the drawings and prints of Barry and Fuseli, both of whom had tackled the subject before him. Their heroic figures of Satan and Death are echoed in Blake’s version.

William Blake (1757–1827), Hecate , or The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy, 1795. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Blake’s visual imagination is unlike anything seen before or since in British art. While doing drudgework as a commercial engraver, he set his imagination free in his poetry and in the images it inspired. His large-scale print Hecate, or The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (1795) derives from his epic poem Europe a Prophecy. Through a complex mix of printmaking techniques and materials and with hand drawing and watercolor added, Blake depicts a Hecate-like figure whose night companions signal her sinister character. Her musculature, like that of her two attendants, recalls the female figures of Michelangelo, which were sketched from male nudes. In this case, the powerful physiques suggest an unnatural, occult strength.

In the period from which the bulk of the collection’s works come, drawings were commodities. Whereas Michelangelo may have valued his drawings as records of design ideas or ways to work out visual problems, collectors in the 18th and 19th centuries prized these same drawings because they were by Michelangelo. From the 18th century on, drawings were exhibited at the Society of Artists, the Royal Academy, and the Society of Painters in Water Colours; sold and reproduced by printmakers like Rudolph Ackermann; and collected by a polite, art-going public. Drawings were collected for a number of reasons, including an interest in a particular subject or artist or a more general desire to acquire an object of cultural prestige.

Richard Cosway (1742–1821), A Figure Lifting a Veil from a Female Figure (Cupid Unveiling Venus?), undated, ca. 1790–1800? The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

To read more, you can order Excursions of Imagination: 100 Great British Drawings from The Huntington’s Collection from the Huntington Store.

Ann Bermingham is professor emeritus of the history of art and architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Bermingham discussed the methods used to create British drawings during the Huntington lecture “The Medium Is the Message: Drawing in Britain, 1750–1950.” You can watch a video of this event on The Huntington’s website.