Kathy Fiscus and the Johnson Well

Posted on Wed., March 17, 2021 by

Barbara and Kathy Fiscus. Barbara Fiscus Collection.

William Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West and professor of history at USC, recently published Kathy Fiscus: A Tragedy that Transfixed the Nation (Angel City Press, 2021), in which he tells the story of a groundbreaking live TV news broadcast of a rescue attempt in 1949 to save a little girl who had fallen down a deep well in San Marino, not far from The Huntington. Deverell explores the event from a multitude of cultural and historical angles, based in part on research he conducted at The Huntington. The following excerpts come from the book’s opening chapters.

Friday, April 8, 1949, arrived cool and breezy in Southern California. Sometime that morning, Alice Fiscus put her two girls in the family car and drove to Union Station in downtown Los Angeles to pick up her sister Jeanette Lyon, Jeanette’s husband Hamilton, and their two boys. The Lyons had traveled up from Chula Vista, near San Diego, to spend the weekend in San Marino so their children, close in age, could play. The Fiscus girls, Barbara (“Babs”) and Kathy, were nine and three. Their Lyon cousins, Stanley and Gus, were ten and five.

Alice Fiscus was recovering from some recent surgery. Her doctor insisted that, as she recuperated, she was not to pick up or hold Kathy. But at the big train station, something startled the little girl—maybe the bustling crowd, or a train whistle, or the rumble of an engine—and Kathy jumped into her mother’s arms. For the first time in six months, Alice stood and held her youngest child. Kathy stayed in Alice’s arms most of the time at the train station. “I always felt that I was so glad . . . to have had the opportunity to do that,” Alice would later say.

Alice, Jeanette, Hamilton, and the children all piled into the Fiscus’s Studebaker and drove home on the Arroyo Seco Parkway. Back at home in San Marino, about a dozen miles northeast of downtown, Alice caught up with her sister. By late afternoon, the kids had gone out behind the house to play in a big and weedy six-acre field. The family’s beloved brown-and-white terrier, Jeepers, romped alongside.

First responders arrive at the scene early in the evening of April 8, 1949. Rick Castberg Collection.

Alice and Jeanette began to prepare dinner, visiting as they did. Alice stood at her kitchen window where she could look out onto the field. The cousins got along well. While their mothers chatted, they ran and played. It was nearing four-thirty, and the sun began its dip toward sunset. “I could see the kids out back playing,” Alice said. “Just running, as children do.” She heard them laugh as they played. Jeepers ran back and forth with them, excited to have so many playmates. Kathy lagged behind the other children, still in the pink party dress she had worn to the train station. They would look back. She would catch up, and then quickly fall behind again.

Alice counted heads. Three, not four. The littlest child was missing. She was just there. Now she was not. Where had she gone?

She went out back and asked the children where Kathy had gone. The others thought she was hiding. Maybe she was angry with the bigger kids for racing ahead of her. Or perhaps she had gone over to the new playground at the K.L. Carver Elementary School at the far end of the field. Alice sensed that something was wrong. She got into the Studebaker and drove over to the schoolyard. Not finding Kathy, she came right back and went out to the field again.

Gus Lyon heard cries near a tractor in the field. He went to investigate. “She’s here!” he shouted. It was Kathy. Alice would later say it was “an absolute miracle” that Gus heard her.

Kathy had fallen into a well.

***

This incident, a little girl fallen down an old well, transcends melodrama—the Kathy Fiscus episode changed lives and changed culture. Every moment would reveal so much in the details, just as each would reveal broader truths beyond the central thread of a child in danger. Certainly, the Fiscus family was never the same again, nor were the lives of others brought urgently and intimately into the story as it unspooled over time. But the reverberations and legacies extend beyond that. The Kathy Fiscus event changed journalism forever. It is one of the most significant events in the history of television media. It changed the lives of families in the United States and beyond who could not, or chose not to, shake free of the event’s impact on how they loved, protected, and even named their children.

Jeanette Lyon, aunt of Kathy Fiscus, at the mouth of the Johnson Well. Rick Castberg Collection.

The primary story begins and ends at the old well. But to get there, to arrive in the field on that pretty spring day, we must first move toward that spot across natural and human histories. Seismology, geology, and hydrology all have a role to play. Natural histories that extend beyond human history—as they always do—affect how people act, how they live, and how they come together, converging on that narrow metal pipe on a Friday afternoon in April 1949.

***

In the summer of 1903, a man named C.C. Johnson drilled a well deep into the big aquifer below San Marino. It was 603 feet above sea level, 572 feet south of Robles Avenue, and 172 feet west of Santa Anita Avenue. The metal casing of the Johnson Well was fourteen inches in diameter for the first 507 feet. From that point, the casing narrowed to ten inches until it reached 784 feet below the earth’s surface. As Johnson’s drill went down, it penetrated the different strata of the earth. Every ten to twenty feet, the sediments changed: soil, gravel, clay, blue clay, cement sand, hard clay.

The cast iron casing would have been perforated—scraped and scratched by cutting tools that opened small gashes—after it had been set into the hole, so that water in the aquifer would seep into the well casing and rise to the earth’s surface.

In Southern California, well-digging had become sophisticated by the 1890s. Even so, it was not uncommon to bring dowsing rods to bear in search of water, as agriculturalists and others looked for the best spots to tap into the big supply of water that lay under the surface of the earth. Wells—the Johnson Well among them—went far below where they first encountered water to tap deep into the aquifer, far down into the water table where there was more water and more water pressure.

Wells bored by drills tended to be small in diameter. Same with those excavated by a cable system: a heavy bit was lifted above the earth and dropped—over and over again—to pulverize the soil and make a deep hole. Though crude, this technique worked well, as the bit tore into the alluvial soils washed down over the millennia from the nearby San Gabriel Mountains.

Dave and Alice Fiscus, parents of Kathy and Barbara Fiscus, sitting on their porch in fearful vigil. Rick Castberg Collection.

All those wells dug into the Raymond Basin tell stories of community: community formation, community relations, and community sustenance. Benjamin “Don Benito” Wilson, a prominent New Englander who later became a Mexican citizen, was the mid-nineteenth century patron of the region. He owned the Rancho San Pasqual, a huge swath of land that is now taken up by the cities of Pasadena, South Pasadena, San Marino, Alhambra, Altadena, and San Gabriel. Wilson knew the waters of the region. He brought water to his property via an aqueduct known locally as the “Wilson Ditch.” He started the first commercial water company of the area in 1875, the Lake Vineyard Land and Water Association, which was purchased by the Alhambra Addition Water Company in 1883.

In 1867, Don Benito’s daughter, Maria de Jesus (“Sue”) married a man named James De Barth Shorb. At least for a time, they lived like royalty on a huge 600-acre ranch that Wilson gave them. They named their ranch San Marino, after Shorb’s grandfather’s plantation in Maryland that, in turn, had taken its name from the tiny European republic.

The name stuck. Shorb developed the property because he knew it had water under it. That knowledge alone was almost enough to ensure its success. But not quite; he failed and went broke. Shorb sold the ranch to Henry Huntington in 1903. Huntington had made plans to relocate to Southern California from San Francisco and New York. He had fallen in love with the ranching landscape when he had been a guest of the Shorbs. At the turn of the century, Huntington came into millions upon the death of his uncle, railroad baron Collis P. Huntington. Within a decade, he doubled that largesse into a formidable dynasty when he married Collis Huntington’s widow, his aunt Arabella. Through the first three decades of the twentieth century, Huntington monopolized the trolley systems in Southern California, adding more millions to his fortune by way of land development (and making Southern California into the decentralized metropolis that it is). He turned much of his money into the greatest book collection ever assembled in American history. The collection, and the art he and his wife acquired, still reside on the San Gabriel Valley property he bought well over a century ago.

The rescue scene. Rick Castberg Collection.

Another of Benjamin Wilson’s daughters, Ruth, who was Sue Wilson’s half-sister, married Huntington’s business partner, George Patton. Father of his famed namesake, the World War II Army general, and indispensable superintendent of much of the operations of rail baron Henry Huntington, the senior George Patton oversaw the digging of several wells for his rich partner in the San Gabriel Valley in the early twentieth century.

As this well-watered part of the San Gabriel Valley grew at the end of the nineteenth century—and answered the agricultural demands of greater Los Angeles and beyond—more wells dove down into the Raymond Basin. That made this part of Southern California one of the most celebrated agricultural regions of the state. With water drawn from the aquifer below, the Johnson Well helped water this fertile landscape. The fields supported a variety of fruit trees: persimmons, peaches, plums, oranges, grapefruit, nectarines, lemons, and apricots.

The San Gabriel Valley grew up around the Johnson Well. Storm drains went under local streets, taking away the water that those springs and little creeks brought from the north to the south. Children who grew up in the area remember sliding into those drains from curbside to play in the damp darkness below or walking far into the old gigantic culverts that emptied water from the vast Huntington property onto the lands and streets below the estate’s grand perch.

In 1907, the San Gabriel Valley Water Company bought up the Alhambra Addition Water Company’s wells, pumps, and pipes, as well as its buildings, its hydrants, and, most important, its water rights. Stock in the San Gabriel Valley Water Company was nearly wholly owned by Henry Huntington’s gigantic holding company, the Huntington Land and Improvement Company. George Patton Sr. served as president of the Alhambra Addition Water Company.

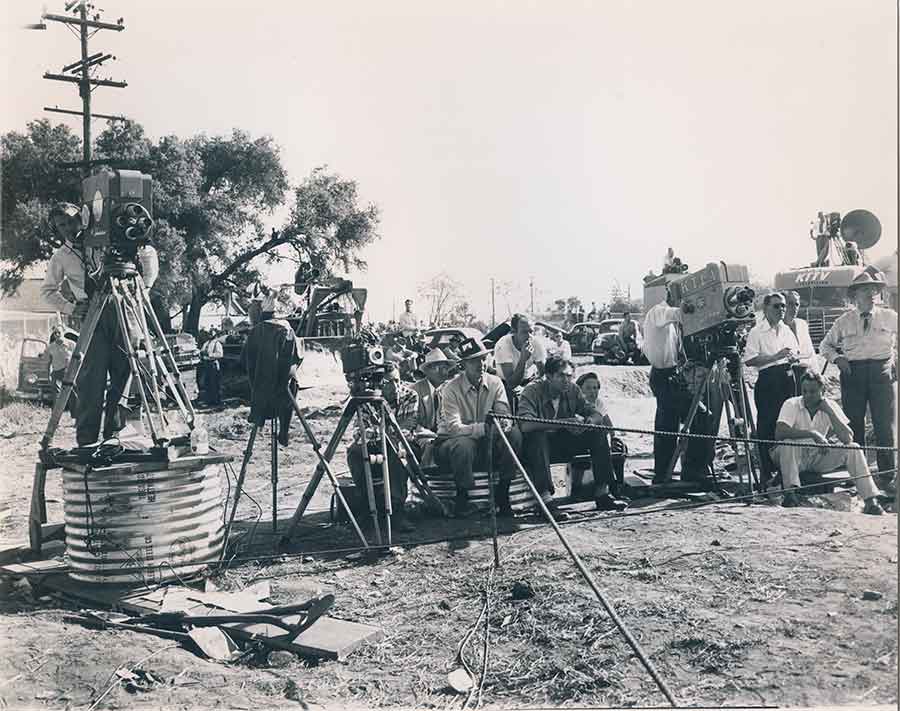

KTTV and KTLA television cameras aim at the rescue attempt: watching, waiting, filming. Rick Castberg Collection.

The metal-and-concrete web atop and beneath the earth—made of wells and pumps, water mains, hydrants, and the pipes—spread across the landscape. Field books of Henry Huntington’s holding company reveal all this in engineering taxonomies, drawings, and measurements. In tiny pencil script—written with what must have been a very sharp pencil—engineers took the measure of all that the water regime on this landscape meant and did. These hundreds of field books—leather-bound and easy to hold in the palm—were tools as much as they were books, the equations, measurements, and renderings within them shaping that landscape around the Johnson Well.

Not long after taking over, the new water company spent $184.40 repairing the casing of the Johnson Well. In the field all around the Johnson Well, engineers marked the irrigation landscape (referred to as “good water-bearing lands”) in their survey books with their particular nomenclature: flumes, valves, ditches, pipes, wells. Other language is in here, too: an “alfalfa patch” marks a boundary, as does a “seedling orange orchard.” At times, the surveyors found relics of the past in their work: a rusty pipe here and there (from earlier well and irrigation work), an old property-line stake. Throughout the 1910s, much attention was paid to the area all around the Johnson Well.

The intersection of Santa Anita and Robles Avenues—so close to where Alice Fiscus would later look out her kitchen window on a late April afternoon—is part of many drawings in these field books. That spot marked an especially wet center of the area, as Johnson certainly knew.

This landscape was not without peril. Building that web of irrigation systems posed dangers to the workers who drilled the wells, dug the ditches, laid the flumes. Those dangers existed beyond the workers, too, and even beyond the years in which those pipes, wells, and drains were in service. George Patton expressed concern over just such danger in a letter he sent up the company chain of command in the summer of 1919. The company owned several of the old tunnels that drained water at the southern end of Henry Huntington’s property. These tunnels worried him. Patton had contacted company officers to complain that neighborhood boys played inside these tunnels. That made him “afraid that some of them will get hurt, or that some damage will be done by lawless persons.” Patton thought the tunnels to be “a menace to the neighborhood.” The water company agreed—it did not need or use these tunnels any longer—and suggested that Huntington’s estate manager might “put in a couple of shots of giant powder or dynamite and cave in these entrances enough so that the boys cannot open them up. We have, on several occasions, closed these entrances, but they continue to dig them up.” Children, water, pipes, and tunnels: it was all cause for concern.

William Deverell, Kathy Fiscus: A Tragedy that Transfixed the Nation (Angel City Press, 2021).

Just after the First World War, the Johnson Well petered out and became inoperative. It had not been in service long, no more than about fifteen years. Maybe the casing had been damaged or bent, deep down in the earth. It was in earthquake country, after all. Maybe the Raymond Fault shook the Raymond Basin and crunched that pipe below. Or perhaps that portion of the aquifer punctured by the Johnson Well had yielded the water it would provide, at least for a while. Reports filed with the state railroad commission—a precursor agency to California’s Public Utilities Commission—show the Johnson Well pulling up just over 23,000 cubic feet of water in 1916. That may seem like a lot, but compared to other wells in service nearby, it was not that much water at all. In the report filed in 1919, the San Gabriel Valley Water Company lists the Johnson Well as “not in use.” Officials may have tried to cap the well, sealing it at the top for safety. That cover may have fallen off, or may have never existed in the first place. We do know that by the spring of 1949, the well was open. It looks to have just sat there, unused, abandoned, and largely forgotten.

In 1929, not long after Henry Huntington’s death, the Western Utilities Corporation bought the San Gabriel Valley Water Company. Western Utilities, in turn, was sold in 1935 to the California Water and Telephone Company. The water rights, the well, and the land around it went with everything else.

The Johnson Well may have stuck up a bit, the casing rising perhaps a few inches from grade level in that field. If there ever was a cap welded on it, or maybe just a metal plate laid across its mouth, it fell off at some point. Or someone yanked it off. Or as the story goes in the neighborhood, it got knocked off by a tractor or other disking machine cutting weeds in that field. Perhaps the machine banged into the well and knocked the cover loose and the operator never put it back. Local lore has it that neighborhood children knew about the well. They liked to throw rocks and other things down it and probably wondered just how far it went down. Weeds grew around the well.

Cap. No cap. No way to know for sure.

William Deverell is the director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West and professor of history at USC.