Lessons Learned: Mulholland's Fatal Dam

Posted on Sat., May 14, 2016 by and

Two historians assess Mulholland's responsibility for one of the nation's worst civil engineering disasters

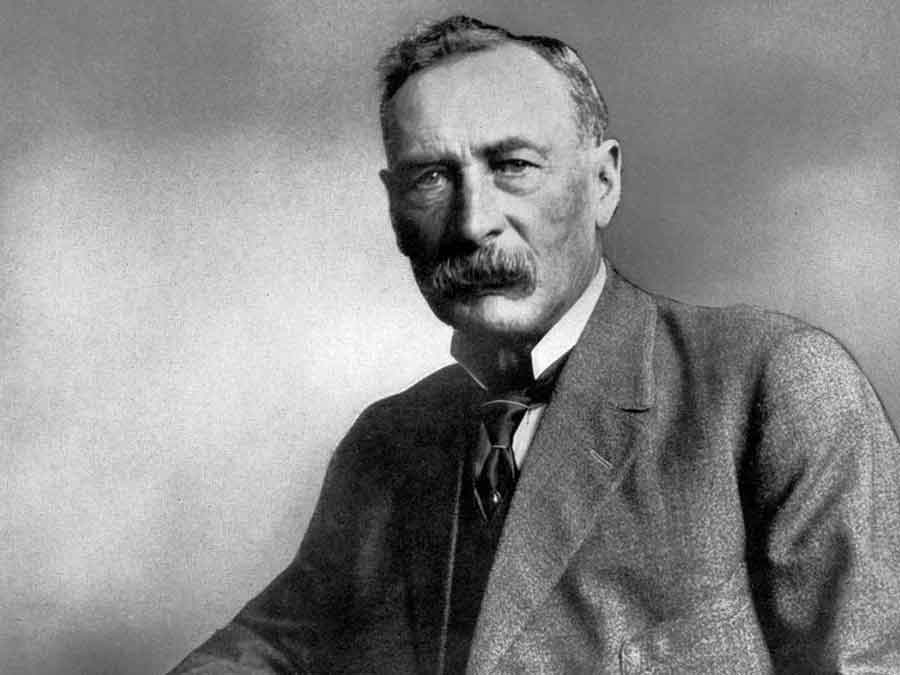

William Mulholland, not long after the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913, as he appeared in the Complete Report on Construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, 1916.

In the critically acclaimed book Heavy Ground: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster, historians Norris Hundley, Jr. and Donald C. Jackson provide a detailed account and analysis of the collapse of the St. Francis Dam, which was located 45 miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles near the present-day city of Santa Clarita. In the early hours of March 13, 1928, a massive wall of water flooded the Santa Clara Valley, leaving roughly 400 people dead in its wake before reaching the Pacific Ocean at dawn.

Considered the worst civil engineering failure in the history of California and the state's second-worst disaster, in terms of lives lost, the collapse of the dam ended the storied career of Mulholland, the man who earlier had masterminded construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. To contextualize Mulholland's responsibility for the dam's failure, the authors relied extensively on items in The Huntington's collections, including the only known copy of the transcript of the Los Angeles County Coroner's Inquest into the disaster. In addition, roughly a third of the book's more than 150 illustrations are drawn from The Huntington's holdings.

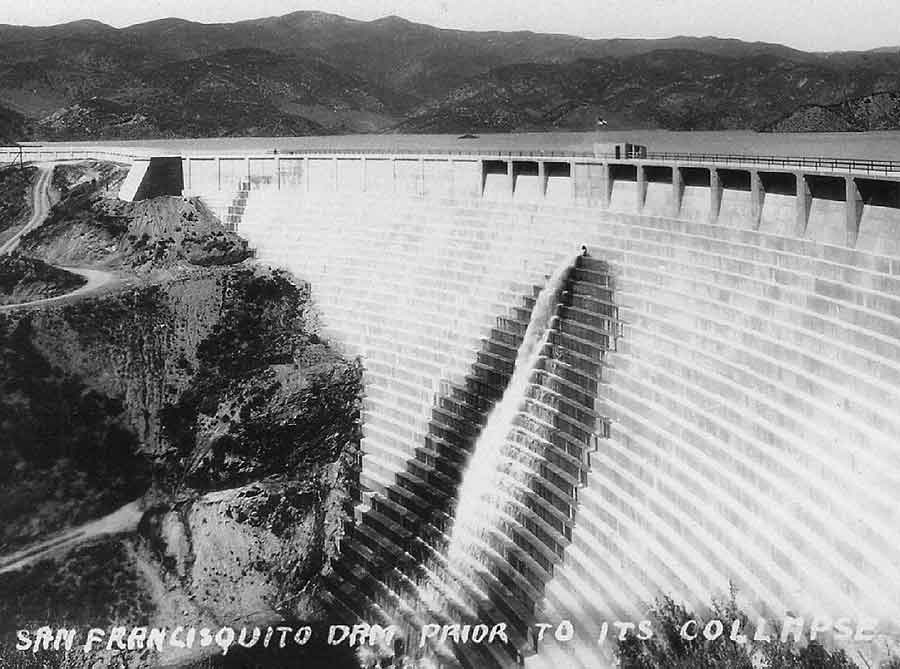

St. Francis Dam, around 1927. From Donald C. Jackson's collection of historic dam images.

By focusing on the design of the dam and its relation to dam engineering practice in the 1920s, the authors build a convincing case that Mulholland himself ultimately was responsible for the dam's collapse. Describing the dam's construction and disintegration in precise detail, as well as the devastating impact of the flood on Santa Clara Valley residents, they also explore such issues as the political dimensions of water-control technology and dam safety legislation in 20th-century California. Most importantly, they probe Mulholland's background, training, and the professional and political context of his work as Los Angeles' most prominent hydraulic engineer.

The following passage is from the book's prologue.

"A Misty Haze over Everything"

It was a few minutes before midnight when Lillian Curtis awoke in her bed. Gazing out the window she witnessed a scene of calm beauty: "There was a large full moon with big white clouds rolling over it." The serenity of the moment, in contrast to the tumult to come, lingered long in her memory. That evening Lillian, her husband, Lyman, and their three children had retired for the night in their modest frame bungalow. It was one of a group of houses built for married employees of the Bureau of Power and Light, tucked in a small ravine off the main San Francisquito Canyon. They lay close by the city's recently built St. Francis Dam. Other city employees and transient workers lived in bungalows adjoining the city's San Francisquito Power House No. 1, about five miles above the dam, or clustered near San Francisquito Power House No. 2, located a mile and a half downstream from the reservoir. The married employees' compound where the Curtises lived lay but a short walk west from Power House No. 2.

Left: Lyman and Lillian Curtis, soon after their wedding in Bakersfield in 1921. Lyman worked for the municipally owned Bureau of Power and Light, and he and his family resided near San Francisquito Power House No. 2. Lillian survived the flood, but Lyman perished along with their two young daughters. Photograph credit: SCVHistory.com. Right: Mazie, Daniel, and Marjorie Curtis in happier times, before the St. Francis Dam disaster. The two Curtis daughters drowned in the flood but Daniel was miraculously saved by his mother. Both mother and son attended the ceremonies in 1978 marking the 50th anniversary of the disaster. Photograph credit: SCVHistory.com.

Also residing in the married employees' compound were Ray Rising, his wife, Julia, and their three young daughters, Delores, Eleanor, and Adaline. Rising had worked for the city for nine months; Lillian's husband had been on the job a few months more. Neither family had been living in San Francisquito Canyon when the St. Francis Dam was completed in May 1926, but the Curtises were in residence when the reservoir, with a capacity of more than 12 billion gallons, came close to filling in May 1927. And—not quite a year later, in early March 1928—both families called the canyon home when water first filled the reservoir and rose within three inches of the dam's spillway crest. "Everything seemed perfectly safe," recalled Lillian Curtis.

Seconds after midnight on March 13, Lillian was startled by a strange apparition in the night sky. "I sat up in bed and looked out the windows toward the dam, which was northeast of us, and I seemed to see a misty haze over everything." Nearby, Ray Rising was jolted awake by a roaring sound that reminded him of tornadoes he had experienced as a youth in Minnesota. He grew fearful about what might be occurring at the dam. Lillian Curtis was now also "hearing a strange noise," and she grabbed her husband and screamed, "The dam has broken!" A 125-foot wall of water, moving at about 18 miles per hour, soon engulfed Power House No. 2, demolishing the plant and killing the on-duty crew.

Left: A low-lying section of Santa Paula, Calif., after the inundation. From Donald C. Jackson's collection of historic dam images. Center left: Drawing of the downstream side of the dam, showing the placement of surviving blocks within the original structure. Not all remnants could be identified, but because the dimensions of the stepped downstream face varied depending on the elevation in the original structure, it was possible to link many of the surviving pieces to a precise location. Failure of the dam started along the lower east abutment, near block 35. From Western Construction News, June 1928. Center right: Detail view of block 5, with broken mica schist deposited on top of the block. Richard Courtney Collection, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Block 5 is visible in the lower-left foreground. Toppled to the right is block 2. This large remnant, along with blocks 3 and 4 (not pictured), sheared off from the surviving center section (block 1) late in the flood. Richard Courtney Collection, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Floodwaters surged up the ravine where the Curtis and Rising families lived. Lillian, several months pregnant, grabbed her three-and-a-half-year-old son, Daniel. In turn, they were picked up by her husband who, after pushing them through a window with orders to "run up the hill," went back for Daniel's two sisters, Mazie and Marjorie. Lillian never saw Lyman or her daughters alive again. For the moment, she concentrated on getting to higher ground, a punishing task amid the brush, silt, and debris filling the rising water. "Mommy," her son called out, "don't let the water get us." With the boy in her arms, she persevered, telling herself, "I must get him out." Breaking free from the tempest near the crest of the hill, she heard a voice. Convinced it was her husband, she crawled over the knoll to safety.

The voice she heard was not her husband's, but Ray Rising's. Rising later recalled that his wife had shouted, "What's that—a wind?" Soon "the sound grew louder and louder, then we heard trees snapping. We went to the door and looked out. Water was coming. We hurried back to get the children. When we got back to the door and tried to open it we could do nothing, as the force of the water held it shut." Then he felt himself "thrown into the air with a force like from an explosion," the water knocking him aside and crushing the timber bungalow. Fighting for air in the blackness and entangled in electrical wires and an uprooted tree, Rising somehow found refuge atop a floating roof. Holding tight until the impromptu raft backed into a canyon wall, he jumped to safety, all the while shouting for his wife and children. But they were gone, joined in death by 23 of his fellow city workers and 42 of their family members who, for at least a few months, had created and shared the community at Power House No. 2. The settlement's only survivors were Lillian Curtis, her son, Daniel, and Ray Rising.

![Left: In the company of his chauffeur George Vejar, a weary Mulholland walked away from the St. Francis site in March 1928. The disaster weighed heavily on him—the Los Angeles Herald noted that he appeared to have aged some 10 years in the traumatic days after the collapse. Mulholland lived on for another seven years, but after the flood he was no longer a dominant force in Los Angeles or in the world of hydraulic engineering. Peirson Hall Papers, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Right: A reviewer for the Wall Street Journal has written that Heavy Ground: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster “does something unexpected. It opens a new perspective onto William Mulholland… [bringing him] to life in all his sharp-elbowed, stubborn glory, saddened and perplexed by the St. Francis Dam debacle yet prideful until the end.” The book, copublished by The Huntington and University of California Press in 2015, is available online at theHuntingtonStore.org. Left: In the company of his chauffeur George Vejar, a weary Mulholland walked away from the St. Francis site in March 1928. The disaster weighed heavily on him—the Los Angeles Herald noted that he appeared to have aged some 10 years in the traumatic days after the collapse. Mulholland lived on for another seven years, but after the flood he was no longer a dominant force in Los Angeles or in the world of hydraulic engineering. Peirson Hall Papers, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Right: A reviewer for the Wall Street Journal has written that Heavy Ground: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster “does something unexpected. It opens a new perspective onto William Mulholland… [bringing him] to life in all his sharp-elbowed, stubborn glory, saddened and perplexed by the St. Francis Dam debacle yet prideful until the end.” The book, copublished by The Huntington and University of California Press in 2015, is available online at theHuntingtonStore.org.](/sites/default/files/mulholland_5.jpg)

Left: In the company of his chauffeur George Vejar, a weary Mulholland walked away from the St. Francis site in March 1928. The disaster weighed heavily on him—the Los Angeles Herald noted that he appeared to have aged some 10 years in the traumatic days after the collapse. Mulholland lived on for another seven years, but after the flood he was no longer a dominant force in Los Angeles or in the world of hydraulic engineering. Peirson Hall Papers, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Right: A reviewer for the Wall Street Journal has written that Heavy Ground: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster "does something unexpected. It opens a new perspective onto William Mulholland... [bringing him] to life in all his sharp-elbowed, stubborn glory, saddened and perplexed by the St. Francis Dam debacle yet prideful until the end." The book, copublished by The Huntington and University of California Press in 2015, is available online at theHuntingtonStore.org.

The torrent sowed death and destruction throughout the night. Not until daybreak did it finally wash into the Pacific Ocean south of Ventura, leaving in its wake millions of dollars in property damage and some 400 lost lives. By then, William Mulholland—the man responsible for building the dam—had been roused from his bed in Los Angeles and driven 45 miles to the site of the now empty reservoir. Acclaimed as a master engineer for his success in creating the modern city's expansive water supply system, the 72-year-old Mulholland had long reigned supreme in the world of Southern California water. But now, as Lillian Curtis and Ray Rising—along with hundreds of law enforcement and civic officials, citizen volunteers, and family members with ties to the Santa Clara Valley—set out in search of survivors, it would be left to Mulholland to explain how his once great dam had turned to rubble.

Norris Hundley, Jr. (1935–2013) was a professor of American history at UCLA and longtime editor of Pacific Historical Quarterly. He also was the author of Dividing the Waters: A Century of Controversy between the United States and Mexico (1966), Water and the West: The Colorado River Compact and the Politics of Water in the American West (1975), and The Great Thirst: Californians and Water, 1770s–1990s (1992).

Donald C. Jackson is the Cornelia F. Hugel Professor of History at Lafayette College and was a 2012 Trent R. Dames Fellow in Civil Engineering History at The Huntington. His books include Great American Bridges and Dams (1988), Building the Ultimate Dam: John S. Eastwood and the Control of Water in the West (1995), Big Dams of the New Deal Era: A Confluence of Engineering and Politics (2006), coauthored with David Billington, and Pastoral and Monumental: Dams, Postcards, and the American Landscape (2013).