Let Us Entertain You

Posted on Tue., Oct. 20, 2015 by

Fanchon and Marco's big "Ideas" revolutionized the 1920s theater world

"The San Francisco Beauties," the first female tap dance lineup on the West Coast, 1927. The dancers are (left to right): Alice Sullivan, Zeta Harrison, Reva Howitt (stage name "Lollipop"), Marge Hacker, Alice Haas, Idis Hacker. In her book, Lollipop: Vaudeville Turns with a Fanchon and Marco Dancer, Howitt wrote that, at the end of 1925, she was selected to be "one of the San Francisco Beauties, Fanchon and Marco's premiere showgirls." Photograph by Harry Wenger.

Chances are you've never heard of Fanchon and Marco. But in the 1920s, millions of Americans had. A wildly successful theatrical firm founded in 1923 by Fanchon Wolff Simon (1892–1965) and her brother, Marco Wolff (1894–1977), produced live stage shows that dazzled moviegoers from Los Angeles to New York. The Fanchon and Marco brand became synonymous with fast-paced extravaganzas that featured elaborate sets and row upon row of winsome chorus girls. In 1932, at the height of the Great Depression, the outfit reported earnings in the seven figures, and Fanchon estimated that she had trained more than 10,000 dancers all told, including some who would go on to become big-time stars, such as Shirley Temple and Ginger Rogers. The press dubbed the sister and brother the "Henry Fords of entertainment" for their assembly-line approach to mass-producing shows. With the recent acquisition of 1,400 photographs donated by the family, The Huntington now has a rare group of pictures depicting hundreds of Fanchon and Marco sets and performers between 1923 and 1935, the organization's heyday.

Born and raised in a large Jewish family in turn-of-the-century Los Angeles, Fanchon and Marco Wolff caught the show business bug early on. As teenagers, the duo cut their teeth on the vaudeville circuit performing a violin and ballroom dance act. By 1919, they had migrated behind the scenes to produce musical revues. An epiphany came with their 1920 California-themed production "Sun-Kist," starring a line of high-kicking beauties. A frenetic mash-up, according to one contemporary critic, "Sun-Kist" whirled between burlesque and grand opera, "with dashes of musical comedy and vaudeville in between." West Coast audiences gobbled it up. The two sensed a lucrative opportunity at the historic crossroads where vaudeville overlapped with the movie industry's meteoric rise and huge audiences.

Left: Marco Wolff, far left, with three unidentified women outside the Los Angeles home office of West Coast Theatres, one of the largest theater owners and operators in the country. Fanchon and Marco did business with them and provided shows for all of their theaters. Photograph by Harry Wenger. Right: Fanchon Wolff, far left, and performers rehearsing for the "Opportunity Idea," 1928. Unidentified photographer.

A movie ticket to a big city theater in the early 1920s often included a full-fledged musical revue with live song and dance. Called "prologues," these stage shows preceded and often promoted the film. Audiences loved them—often more than the silent film itself. Movie executives and savvy theater owners saw them as a high-profile way to keep filling seats. The problem? A show was costly and fleeting, as it often related to a specific film. A prologue typically closed when a movie left the theater after a brief one- to two-week run. Smaller houses simply could not afford them, given the logistics and expense. Enter Fanchon and Marco. These two vaudevillians-turned-producers hit upon an enterprising scheme to generate hundreds of touring prologues, meeting a nationwide demand for them in a big way.

"The secret to a good prologue," Fanchon told one reporter who had asked for an accounting of F&M's success, "is to have the most entertainment in the least amount of time." Fanchon and Marco entered the prologue business in 1923 with an innovation they called the "Idea," a compressed entertainment grab bag based on a broad and often nebulous theme. An F&M Idea promised big laughs, lavish costumes, and a grand finale in a snappy 40 minutes, tops. Themes ran from the fairly predictable ("Hollywood Beauties," "Dancelogue," "Romance") to the timely ("Radio," "Aviation") to the outré ("Hot Mama Goose") to the downright weird. The "Salad Idea" was one such oddity, a production from the fertile mind of Fanchon, who dreamed it up over dinner one night. Musicians played in chef's caps while dancers, dressed like lettuce leaves and asparagus stalks, emerged on stage from a colossal bowl. According to one of the company's long-term chorus-line hoofers, Reva Howitt (aka Lollipop), the dancers were not amused.

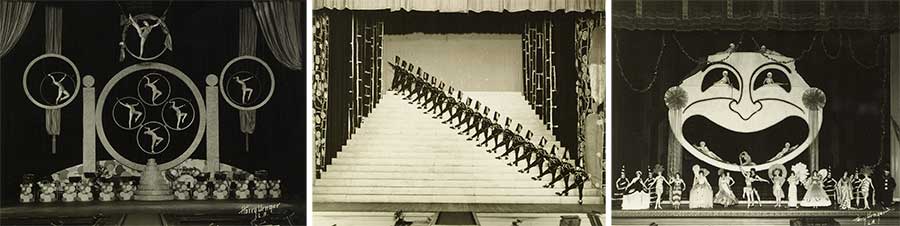

Left: "Hoops M'Idea," 1927. From a display advertisement in the Los Angeles Times for the Loew's State Theater: "On the stage...Fanchon & Marco's 'Hoops M'Idea' featuring Renoff and Renova, world's greatest classical dancers, Sunkist Beauties—All Beauts! Juanita Wray, prima donna of 'Castles in the Air' – The Lovetts – Scotty Westen, Natalie Harrison." Photograph by Harry Wenger. Center: "Stairway of Dreams Idea," 1928. From a display advertisement in the San Jose Evening News: "Fanchon and Marco's 'Stairway of Dreams.' Biggest stage spectacle in months with 20 great girls. Flo and Ollie Walters, Woods Miller, and of course, Milt Franklyn and his band!" Unidentified photographer. Right: "Masks Idea," 1927. According to the Los Angeles Times: "On the stage, Rube Wolf 'world's homeliest musical shriek' makes his debut at the Metropolitan in Fanchon and Marco's 'Masks.'" Rube Wolf, who dropped one f from his surname, was Fanchon and Marco's brother and an orchestra leader for the company; he also played trumpet. Photograph by Harry Wenger.

Aside from offering entertainment value that packed a swift punch, sheer volume proved an equally important element to the duo's success. Ideas were churned out at the rate of one per week in a block-long Hollywood facility that employed a phalanx of choreographers, musicians, carpenters, electricians, seamstresses, "advance men," stage directors, scenic painters, and the hundreds of others needed to create and promote these pre-packaged shows. Ideas required a deep well of talent, and Los Angeles provided an ample, ever-renewable supply. More than 1,000 performers were cast in the dozens of F&M Ideas circulating around the nation in 1932. Marco, who oversaw the business side of things, ticked off an extensive list that included novelty acts (whistlers, mind readers, "iron jaw experts," and "punching bag artists"); animals (dogs, elephants, horses, four grizzly bears); musicians; acrobats; contortionists; a plethora of comics (including a "nut comic" and a "Dutch comic"); and dancers of all sorts. Fanchon openly credited the company's Southern California locale: "If you need a Japanese knife thrower or a Hindu snake charmer, or a rainmaker or a long-haired prophet—there they are, as quick as you can get them on the phone...Los Angeles is the most amazing place in the world!"

From left to right: A dancer wearing an "asparagus top" headpiece for the "Salad Idea," photograph by Harry Wenger; a dancer in the "Peacock Idea," 1927, photograph by Paralta Studios; a dancer in the "Masks Idea," 1927, photograph by Paralta Studios; Norma Wilson in the "Masks Idea," 1927, photograph by Paralta Studios.

Above all else, chorus lines of young women became the signature Fanchon and Marco touch. There were the Sunkist Beauties and San Francisco Beauties, small troupes of six to eight. Yet, the Fanchonettes were the pièce de résistance. The groups of two dozen dancers—enough to fill a stage—were the creative brainchild of Fanchon, as the name suggests. She supervised each Fanchonette's selection and artistic training through the popular dance school F&M opened in 1926. Fanchon prized "youth and naturalness" in her dancers (most of whom ranged between 15 and 20 years of age), giving high marks to intelligence as well. All the better to swiftly learn the complicated and ever-changing dance numbers, many of which Fanchon devised herself.

To be a Fanchonette required precision timing and stamina, not to mention guts. A crowd-pleasing number might draw on a repertoire of steps from ballroom, ballet, tap, and jazz. A Fanchonette could be required to perform an arabesque aloft while clutching a rope or suspended from a swing. She might be wearing an elaborate spider costume while crawling across a giant web or a cumbersome hoopskirt that concealed a pair of stilts. The "Pirate to a frenetic grand finale in which her tin-soled shoes threw off blue sparks! In the popular naval-themed "Gobs of Joy" (gob being a slang term for a sailor), a pair of Fanchonettes sat astride enormous battleship guns that discharged a pyrotechnic finish (see last image, center).

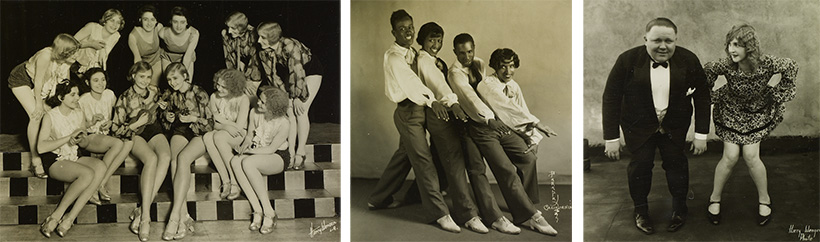

Left: "Seeing Double Idea," 1930. A reviewer in the Los Angeles Times commented: "whether they are real twins or stage twins, in every case, doesn't matter. Each pair looks convincingly alike, and they include comedians, tumblers, fun-makers, and dancers." Photograph by Harry Wenger. Center: The Four Covans (1928), a tap dance group featuring dancing sensation Willie Covan (third from left), his brother Dewey, and their wives. Photograph by Paralta Studios. Right: Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle and Nita Martan, stars of "College Capers Idea," 1928. According to the Los Angeles Times: "F&M, gunning for big names for their stage Ideas, have just signed...Arbuckle to star in person in 'College Capers'...in the role of the fat campus freshie." Photograph by Harry Wenger.

The life of a Fanchon and Marco performer could be grueling, and never more so than when out on the road. By 1928, F&M Ideas were playing in more than 100 theaters from San Diego to Vancouver on the West Coast, and across the country in Colorado, Montana, Illinois, Missouri, and New York, in cities large and small. A show complete with sets, costumes, and a cast of 40 to 50 would arrive at a venue to perform four to five shows each day. After a week or two, the production would take an overnight train, repeating the entire process at a new venue with rarely a day off. Dancers were paid a little more than $30 per week and typically made the six-month circuit two times, three at the most. Even so, one wide-eyed Fanchonette from Iowa expressed the sentiments of many an up-and-coming young dancer in appraising her F&M tour as "glamorous and well-paying."

Despite the ascendency of the "talkies" and the catastrophic Great Depression, Fanchon and Marco continued to do surprisingly well into the 1930s. F&M opened a theatrical school in 1933, training myriad wannabes and budding stars, including the likes of Judy Garland, Bing Crosby, and Cyd Charisse, among others. Even so, by 1936, entertainment appetites had shifted, and F&M shuttered the Hollywood production facility for good.

Left: "Yachting Idea," 1926. Unidentified photographer. Center: "Gobs of Joy Idea," 1929. Photograph by Harry Wenger. Right: "Moonlit Waters Idea," 1927. Variety commented: "F&M have taken advantage of the pop song of the same title and utilized other 'moon' songs for this newest of Ideas."

Fanchon and Marco may have burned brightly as the impresarios of those strange theatrical amalgams called "prologues," but demand for the genre was over in a flash. While neither the first nor only people in the prologue business, the two cornered the niche market with efficient panache and grand, go-for-broke style. Today little F&M business history exists: no records, receipts, ledgers, or files, despite F&M's having employed thousands of people in its day. This fact makes The Huntington's 15 volumes of photographs and small group of clippings and programs an indispensable resource for scholars. The volumes, which appear to have been organized chronologically, contain images—often four to a page—that served as a corporate inventory of hundreds of the Ideas, both sets and performers. Though accompanying information is scant, several theater and dance specialists have already begun to identify members of specific casts, such as the Mexican-American Romero brothers, called the "Aristocrats of Dance," who appeared in many Spanish-themed Ideas.

In later years, Reva Howitt reminisced that she and many fellow performers considered their brief time with F&M to be a labor of love. "I speak for my hundreds of counterparts...who are lost in obscurity but who provided entertainment for the public with zest, enthusiasm, proficiency, responsibility, and color," she wrote. "Hurrah for us!"

Jennifer A. Watts is curator of photographs at The Huntington.