Lincoln’s Body, in Life and in Death

Posted on Wed., Oct. 29, 2014 by

Richard W. Fox ties Lincoln's body to his words and deeds

Abraham Lincoln, the Martyr, Victorious (1866) by John Sartain (1808-1897), after a design by W. H. Hermans, explores the almost religious ascension of Lincoln following his assassination on Good Friday, 1895. Says author Fox, "He wasn't divine like Jesus, just divinely chosen." The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On April 21, 1865, Abraham Lincoln's funeral train left Washington, D.C., for Springfield, Ill. It offered northerners "a moving shrine they could approach as pilgrims," writes Richard Wightman Fox in his new book, Lincoln's Body: A Cultural History (to be published by W. W. Norton on Feb. 9, 2015). As many as a million people caught a glimpse of Lincoln's face as he lay in state in a succession of 12 cities; another 7 million people, almost one-third of the northern population, watched silently as his train passed by, heads uncovered in mourning.

In an interview with Huntington Frontiers, Fox, a history professor at the University of Southern California, explains how Lincoln's body fascinated Americans throughout his life and even after death. Famous for his "ugly and grotesque" features, he won people over by enthusiastically joking about his coarse looks. As president, he made himself accessible to the people, and they witnessed the physical cost of his service. Had he lived on into the 1870s or 1880s, he would have been cherished as the republican hero who had given his body to the Union cause. Killed in 1865, he became the martyr who in death could symbolize all the Union's lost soldiers.

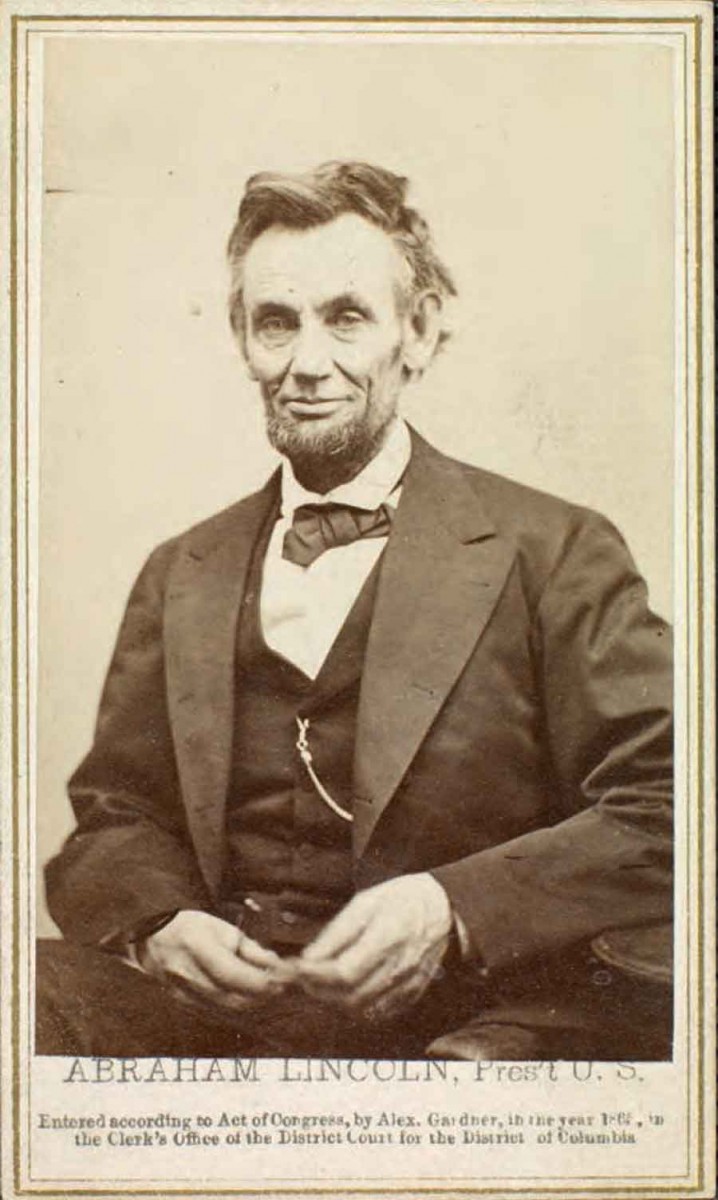

Q: Your frontispiece features one of the last portraits of Lincoln, a photograph by Alexander Gardner that accentuates his weather-beaten appearance.

A: Photography emerged in the 1840s, just in time to preserve the look of Lincoln's body over the last two decades of his life. In the 1860s, cheap cartes-de-visite made his image available to millions of northerners, and many southerners (including a few slaves) owned prints of his face taken from newspapers and magazines. Pictures like Gardner's, bringing out his wrinkles and facial crevices, showed how fully he'd given his body up to the twin causes of union and emancipation. This Lincoln has been withered by the war years. By Feb. 5, 1865, the date of this photo, he appeared hollowed out.

Richard W. Fox says an 1865 photograph of Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Gardner "showed how fully he'd given his body up to his body up to the twin causes of union and emancipation." This photo, from The Huntington's collection, is the carte-de-visite format of the image Fox describes. Measuring about two by three inches, it was popular as a keepsake.

Yet the Gardner photo registers satisfaction as well as fatigue. Lincoln conveys physical relaxation, and for once he almost smiles. We can't miss his contentment. He doesn't know when the war will end, but he does believe it will end with Union victory and the destruction of slavery. Less than two months later, as it turned out, he would be walking the streets of Richmond with his son Tad, surrounded by thousands of exuberant former slaves.

Q: At one point you intended to focus exclusively on the story of the funeral procession—the literal movement of Lincoln's body through the country by train. Why did you decide to expand the story, tracing Lincoln's symbolic path all the way to the 21st century?

A: Initially, I thought the story of Lincoln's body would finish with his interment in Springfield, Ill., on May 4, 1865. But the more research I did, the more I realized that northerners and southern blacks weren't done mourning for Lincoln just because the funeral journey had come to an end. Whitman made that point in his 1865 elegy to Lincoln, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd." His grieving for Lincoln, he wrote, would be repeated every spring, a perennial growth in his heart.

Reflecting on Whitman opened me up to the reality that in early May of 1865 millions of Americans had just begun to experience and make sense of the loss of Lincoln. For many blacks and northern whites, the feeling of bitter loss persisted for generations. They believed Lincoln had given his body up for them. They shared a profound love for Lincoln, but the intensity of that love created divisions, too, as Democrats and Republicans fought over the political meanings of his physical sacrifice.

In an interview with Huntington Frontiers, author and historian Richard W. Fox says an 1865 photograph of Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Gardner "showed how fully he'd given his body up to his body up to the twin causes of union and emancipation." The photo above, from The Huntington's collection, is the carte-de-visite format of the image Fox describes. Measuring about two by three inches, it was popular as a keepsake.

Q: You explain that people yearned not only for last words from Lincoln, but also a glimpse of his body. Was this typical of mourning in the 19th century?

A: Nineteenth-century Americans wished for last words from their dying loved one, and they wanted to witness those words being spoken at the deathbed. Lincoln died about nine hours after being shot, with a sizable group of friends and officials standing around his deathbed. But he'd lost consciousness at the moment of the attack, and there would be no last words.

The recent rise of embalming made it possible to put his body on display in city after city, so that citizens could bid him a personal farewell. And the people got busy creating a set of virtual last words. They went back to the Second Inaugural and pulled out the line "with malice toward none, with charity for all." Newspapers published his favorite poem, "Mortality," and they were so eager to bestow some last words on him that they often mistakenly claimed Lincoln had written the poem himself. (It was written by William Knox in the 1820s.)

Q: In the days, weeks, and months that followed there was a proliferation of eulogies. You call these "verbal memorials," almost on par with the physical monuments that would be built.

A: In 1865 people regarded great orations as permanent contributions to the life of the republic. Memorial orations, if truly inspired, could keep memory of "the illustrious dead" fresh and vital for generations. At the time, the eulogies by Ralph Waldo Emerson, historian George Bancroft, and Senator Charles Sumner were held up as the best of the lot, along with Walt Whitman's "Lilacs." Frederick Douglass made important speeches about Lincoln in 1865, too, but it took him another 11 years to create his great eulogy of the assassinated president. His oration at the dedication of the Emancipation monument in Washington, D.C., in 1876 may be the greatest single speech about Lincoln ever given.

Q: How did Frederick Douglass' speech differ from those of white speakers who preceded him?

A: African-Americans reacted to Lincoln's death in 1865 quite differently than white northerners did. North and South, blacks felt they had lost their irreplaceable champion. Most northern whites loved Lincoln, too, but they mitigated their sorrow by rehashing their article of faith that this great republic could replace any chief magistrate with another one just as good. In the spring of 1865 many of them thought that Andrew Johnson was an improvement on Lincoln—he wouldn't go easy on the traitors, they thought, while Lincoln might have let them off scot-free. Even Douglass went along with that idea.

But the vast majority of African-Americans feared for their future without Lincoln. And by the time he spoke in 1876, Douglas had largely come around to their view, praising his fellow blacks for their wisdom in staying attached to the fair-minded Lincoln. True, said Douglass, he was first and foremost the "white-man's president." But by 1863 he had demonstrated his commitment to black freedom. In 1876, Douglass told blacks to keep on cultivating the memory of Lincoln the emancipator. Looking back, whites have African-Americans to thank for remembering—from the 1860s to the 1960s—Lincoln's zeal for the principle of republican equality. That was the century when millions of whites forgot about it.

The stereograph by Ridgeway Glover (1831-1866) shows the hearse that carried Lincoln's casket through Philadelphia's packed streets on April 23, 1865. Many wore mourning badges, like the one on the right, which features an 1865 gem tintype photograph by Anthony Berger for the Mathew B. Brady Studio.

A Nation in Mourning

The stereograph by Ridgeway Glover (1831-1866) shows the hearse that carried Lincoln's casket through Philadelphia's packed streets on April 23, 1865. Many wore mourning badges, like the one on the right, which features an 1865 gem tintype photograph by Anthony Berger for the Mathew B. Brady Studio. These two images will be published in a forthcoming book, A Strange and Fearful Interest: Death, Mourning, and Memory in the American Civil War, by The Huntington's curator of photographs, Jennifer A. Watts. The book is a companion volume to the 2012 exhibition curated by Watts.

Q: How did one of Lincoln's own great orations, the Gettysburg Address, take on new meaning?

A: By the end of the 19th century, whites had come to love the Gettysburg Address much more than the Second Inaugural Address, partly because the Gettysburg speech doesn't mention slavery. The Second Inaugural blasts away at the original American sin of slaveholding, a sin shared by North and South. White northerners and southerners found it much easier to reunite when the memory of slavery and its continuing effects were suppressed. The Gettysburg Address spoke generally of a "new birth of freedom," but as the decades passed, more and more whites forgot the obvious reference Lincoln was making in 1863 to the Emancipation Proclamation—which had gone into effect 10 months before his Gettysburg speech.

It's hugely ironic that white northerners learned to venerate the Gettysburg Address at a time—the late 19th and early 20th centuries—when few of them took seriously its words "all men are created equal." Yet the white northern children who memorized the Gettysburg speech in grammar school in the early-to-mid-20th century were primed to discover new meaning in it when civil rights leaders adopted the Lincoln Memorial as an organizing site starting in the 1930s. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech in 1963 took much of its power from his standing right below the enormous Lincoln statue. That speech tripped a wire in many young whites in the North and South. The northerners, already used to cherishing the Gettysburg speech, could fold King;s oratory right into it. For them, King made Lincoln live again as the nation's emancipator. Blacks needed little reminding. They had kept Lincoln love as their emancipator for a full century.

Cover of Richard Wightman Fox's book, published by W. W. Norton.

Q: I suppose by using the Lincoln Memorial as a backdrop, Martin Luther King Jr. represented the convergence of verbal and physical memorials to Lincoln. Can you say a little bit about the creation of the Lincoln Memorial?

A: The statue was unveiled in 1922, a tremendous sculptural feat by Daniel Chester French and a dazzling architectural achievement by Henry Bacon. But some critics bemoaned the elegantly "Greek" style of the monument. They wished for some kind of simple, resoundingly "American" structure, far more fitting in their eyes for the rail-splitter who had stridden in from the "west."

And some black observers faulted the dedication ceremony, not just for placing invited black guests in a bank of segregated seats, but because the main white speakers—President Harding and Chief Justice Taft—downplayed Lincoln's role as emancipator, hailing him instead as the reunifier of the nation. Black groups began assembling informally at the memorial later in the 1920s. The famous concert there on Easter Sunday in 1939—with African-American contralto Marian Anderson singing spirituals for an audience of thousands (and many more listening on the NBC Blue Network)—marked the rededication of the Lincoln Memorial to the emancipator.

Q: What about the way Lincoln is depicted in Daniel Chester French's sculpture?

A: French sculpted a seated Lincoln to give him commanding authority along with an aura of eternal rest. The most famous Lincoln statue before 1922—Augustus Saint-Gaudens' 1887 standing Lincoln in Chicago—did much more to capture his human character. It shows him poised in thought, just before beginning to address some unspecified audience. French had a different aim: to evoke an everlasting Lincoln, to show his enduring power as the face and body of the nation. Yet when you look closely, you realize that French's transcendent Lincoln is not completely at rest. His hands, fingers, and legs are tensed, almost in motion. This president is still concentrating on something, perhaps on the verge of doing something, just like the standing Lincoln of Saint-Gaudens in Chicago. His massive marble chair can scarcely contain him.

Q: What happened in the late '60s to make Lincoln seem somehow less appealing?

A: The Vietnam War split the civil rights movement, and a radicalized Martin Luther King Jr. took many black and white liberals with him when he broke with Lyndon Johnson, opposing the war and arguing for more substantial equality of incomes. The movement for legal equality from 1955 to 1965 had found Lincoln very useful. But the antiwar and antipoverty campaigns of the late 1960s found him ver unhelpful. By the time King was assassinated in 1968, he was arguing for a guaranteed annual income and for ending the war so that resources could be redirected to solving social problems at home. To many liberals and radicals, black and white, Lincoln now seemed to be little more than the face of a warfare state.

Into the 1980s, Gore Vidal pressed the case against seeing Lincoln as a symbol offering inspiration for progressives. Interestingly, Vidal campaigned against Lincoln's body as much as he did against Lincoln's words and deeds. He eagerly spread the unsubstantiated rumor that as a young man Lincoln had contracted syphilis.

Q: Your book notes the resurgence of Lincoln as a liberal hero in the late 1980s and early 1990s, most notably with the PBS Civil War series by Ken Burns. Which version of Lincoln would appeal to Barrack Obama, who in 2007 declared his candidacy for president in Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Ill.?

A: The historic contribution of the first black president was to make Lincoln his hero while silently affirming that Lincoln no longer carries special meaning for African-Americans as a group. Lincoln will now mean something to whichever individuals recognize his genius, black or white. He can serve as a model for any and all young people who, like Obama, believe that this exceptional American nation can give them the same fair chance that Lincoln received. One of Obama's certifiable achievements is to have cemented the post-Vidal reconciliation between liberals and Lincoln. That's partly why conservatives so rarely hail Lincoln anymore. The last time a national Republican leader called the GOP the party of Lincoln may have been in 2008—when Rudy Giuliani did so after quitting his campaign in the wake of his poor showing in the Florida primary.

Q: Your book's title, Lincoln's Body: A Cultural History, also has a religious dimension.

A: Before his assassination in 1865, Lincoln was well on his way to achieving immortal fame as a republican hero—with a small "r." That's what he would have remained had he lived into the post-Civil War era. He would have been remembered forever as the president who more than any other had put his body at the disposal of his fellow citizens—admitting them freely to his office, savoring his contact with them outside the White House. He would have been remembered for the bodily toll exacted by his saving of the Union.

But his martyrdom—on Good Friday—at the hands of an assassin sympathetic to the Confederacy created an immediate collision between the republican assessment of his service and a religious understanding of it. Now he resembled Jesus as much as George Washington. He wasn't divine like Jesus, just divinely chosen. It seemed obvious to most northerners that on April 14, 1865, God had intervened to remove Lincoln, and to give him a special post-mortem mission as a symbol of peace and charity for all.

Over the long haul, blacks did a better job than whites at keeping Lincoln's religious and republican meanings both in play. Like most whites, blacks took Lincoln's bodily sacrifices as somehow God's doing. But unlike whites, they kept insisting that God wished Lincoln's life to stand for the granting of full civic freedom to all.

Interview conducted and edited by Matt Stevens, editor of Huntington Frontiers.

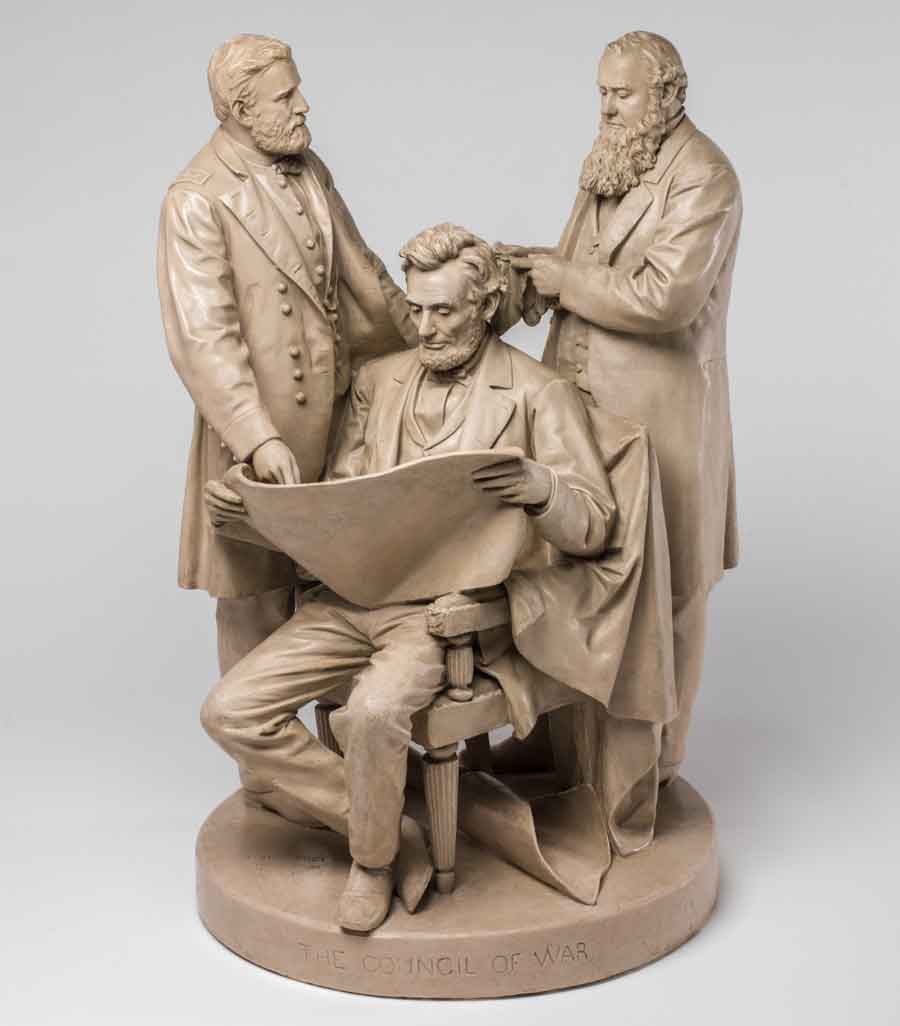

John Rogers, Council of War, 1868

A Sitting President

We asked Richard W. Fox to comment on the depiction of Lincoln in a statue from The Huntington's American art collection—John Rogers' Council of War, made in 1868, at a time when memorial images of the 16th president proliferated.

Rogers has given us an idealized portrait of Lincoln. The statue resembles Lincoln rather than truly looking like him. His face has been smoothed over and softened. When the president was dealing with Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in the 1860s, he was much more haggard-looking than this. One would never guess from this portrait that even Lincoln's friends thought of him as "homely" and "ugly" in his physical features. They were continuously struck by his "grotesque" lack of symmetry: his head was too small for his elongated (six-foot-four) frame, his shoulders too narrow, his arms and legs too long. He couldn't compare to George Washington in the beauty of his physical proportions. Of course, they loved Lincoln for the wit and caring and intelligence that always broke through to animate his ungainly body and his off-putting face.

The other thing that strikes me about the statue is that Lincoln is not visibly engaged with either Grant or Stanton. He's studying the map. And Grant, as much as he's pointing at the map, too, isn't looking at Lincoln. He's looking at Stanton. Lincoln seems to have withdrawn into his own world. He's biding his time and keeping his own counsel, but you can still infer that he's the one in charge. Sooner or later he'll be issuing orders.