Lincoln’s Last Breath

Posted on Mon., Nov. 3, 2014 by

How Lincoln's death helped revive the practice of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation

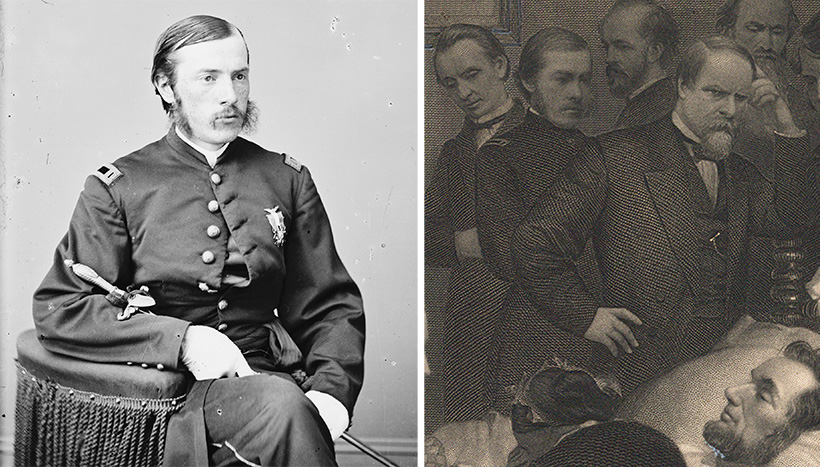

In The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln, artistic license allows artist John B. Bachelder to depict all 47 people who visited the dying president over the course of the night in one fantastical scene. Among those shown is Army surgeon Charles A. Leale, the doctor who rushed to Lincoln's side after the fatal shot by John Wilkes Booth. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

"In no respect do men come nearer to God than in restoring life to those who seem to be dead."

—Dr. Anthony Fothergill Translated from a Latin phrase, quoted in "On the Art of Restoring Animation," 1802

"The President still breathes," began the dispatch sent to the press before dawn on April 15, 1865. Just hours after Abraham Lincoln had been shot, Edwin M. Stanton, Lincoln's secretary of war, provided ongoing updates from the boarding house across the street from Ford's Theatre, where Lincoln had been watching a performance of the British comedy Our American Cousin. Lincoln had appeared dead after being shot by John Wilkes Booth, but a young Union Army surgeon named Charles A. Leale had resuscitated him almost immediately. Only 23 years old and just weeks out of medical school, Leale had gone to the theater to get a glimpse of Lincoln and ended up responding to Mary Todd Lincoln's cries for help. He had vaulted over rows of seats to gain entry into the presidential box. As Leale recounted in 1909 on the centennial of Lincoln's birth, when he reached the president, "he appeared to be dead. His eyes were closed and his head had fallen forward. He was being held upright in his chair by Mrs. Lincoln, who was weeping bitterly."

Leale initially thought the president had been stabbed but then quickly found the gunshot wound in the back of his head, behind Lincoln's left ear. Using only his fingers, Leale attempted to relieve pressure from the president's brain by removing an obstructing clot of blood from the wound. Leale then initiated a form of manual artificial resuscitation popular at the time called the Silvester maneuver. He cleared Lincoln's airway, manipulated his arms, and pressed on his diaphragm to draw air in and out of the lungs.

Leale repeated the maneuver several times but got nothing more than "a feeble action of the heart and irregular breathing." The young doctor concluded, "Something more must be done to retain life. I leaned forcibly forward over his body, thorax to thorax, face to face," he wrote, "and several times drew in a long breath, then forcibly breathed directly into his mouth and nostrils, which expanded his lungs and improved his respirations." He then placed his ear over Lincoln's thorax and could feel Lincoln's heart beating. "I arose," Leale wrote, "then watched for a short time, and saw that the President could continue independent breathing and that instant death would not occur."

With the assistance of a small group—including Charles S. Taft and Albert F. A. King, two physicians who had arrived at Lincoln's box shortly after Leale had resuscitated the president—Leale carried Lincoln out of the theater. Lincoln was still alive and breathing, but as they exited, Leale uttered the dire prognosis that was quickly telegraphed all over the country: "His wound is mortal; it is impossible for him to recover."

Lincoln would continue breathing for nine more hours. What seems most remarkable about that evening is not that a young doctor managed to prolong Lincoln's life for so long but that he knew how to administer the technique that we now refer to as mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. For more than 50 years before Lincoln's assassination, artificial resuscitation—in the form of mouth-to-mouth—had been widely renounced by the medical community and more or less abandoned. The practice was likened to breathing "dead air" into an already non-breathing victim.

At the time of Lincoln's death, "the correct ideas of resuscitation," including mouth-to-mouth, which had previously been accepted and practiced in the 18th century, had been, wrote one physician, "discredited, discontinued, and then largely forgotten."

Leale, however, had studied under progressive physicians who were expert in gunshot and head wounds. His training at Bellevue Hospital Medical College, in New York City, was exceptional for the time, and it is safe to assume Leale had been exposed to the mouth-to-mouth method in principle, if not in practice.

Leale wrote several reports about his response that night, including a version that was lost to history until an archivist named Helena Iles Papaioannou discovered it in 2012 at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. While Papaioannou's discovery thrilled historians, the more detailed paper trail for the history of resuscitation may well be a public address delivered by Leale in 1909 on the 100th anniversary of Lincoln's birth. In that account, published as Lincoln's Last Hours, Leale for the first time revealed details of the lifesaving efforts that he had not included in any of his earlier reports. "History now demands," he began, "that it is my duty to give the detailed facts of President Lincoln's death as I know them. I this evening for the first time will read a paper on the subject."

This portrait of Dr. Charles A. Leale (left), dating from 1860-70, was the model for his image in The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln (detail shown at right). He is standing between two other doctors in the background. From left to right, they are Dr. George B. Todd, Dr. Leale, and Dr. Charles S. Taft.

The 1865 report found by Papaioannou, written soon after Leale left Lincoln's bedside, is clinical and perfunctory, but the account he read aloud in 1909 was full of emotion and intimate details of the resuscitation. It is one of very few accounts of mouth-to-mouth published in the late 19th or early 20th century and helped bring attention to its effectiveness over widely accepted and practiced manual types of resuscitation, like the Silvester method.

Given the popularity of Lincoln as president and martyr, Leale's dramatic 1909 account likely served to influence others who went on to advocate for the use of mouth-to-mouth. A month after Leale described his resuscitation of Lincoln, an endorsement of mouth-to-mouth was published in the revered medical journal The Lancet. The article, by Sir Arthur Keith, documented the history of resuscitation, including how the mouth-to-mouth method had preceded manual forms. Keith concluded, "If it should happen that I may be found in an apparently drowned condition, I sincerely hope that my rescuer will apply this method to me as my first aid."

Keith's article and others published over the next several decades became part of the medical foundation from which mouth-to-mouth was "rediscovered." Its use was reintroduced formally in the late 1950s by two anesthesiologists, James Elam and Peter Safar, the latter considered to be the father of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Elam was the first to prove that the air breathed into someone via mouth-to-mouth had adequate oxygen, and Safar combined chest compression with mouth-to-mouth to create CPR as it is practiced today. In 1957 the U.S. military adopted mouth-to-mouth, and the following year it was accepted and endorsed by the American Medical Association. The American Red Cross provided training that furthered its widespread use and acceptance in the United States and beyond.

As we commemorate the 150th anniversary of Lincoln's death next spring, it seems ironic that mouth-to-mouth resuscitation is at another low point in popularity as "hands-only CPR" is being recommended as the method of choice. This shift has been driven by fears of transmissible disease and an acknowledgment that untrained bystanders often do it incorrectly.

Although Leale might have felt a degree of desperation and self-consciousness in performing such an unfashionable and intimate lifesaving effort on the president, he demonstrated remarkable self-possession and composure in doing so. His documents—written soon after the assassination and much later in 1909—also demonstrate the unremitting kindness and affection he extended to Lincoln and his family throughout the chaos and trauma of those final hours.

The last breaths of the president, restored so briefly and heroically by Leale, were and remain a significant part of the history of resuscitation. At the end of his 1909 address, Leale appears to have achieved some sense of peace with the supporting role he played in aiding Lincoln, albeit with death as the outcome. "I had been the means, in God's hand," he said, "of prolonging the life of President Abraham Lincoln for nine hours." Leale's care extended Lincoln's last breaths long enough for the president to be removed safely from the theater. That act gave Lincoln and his family privacy, and it also gave the government and the nation time to prepare and brace itself, as Leale described, for the profound loss of the "Savior of his Country."

Aizita Magaña is a public health official in Los Angeles County and an independent researcher at The Huntington. She is writing a book on the history of breathing and the breath.