Mourning Attire

Posted on Fri., Oct. 3, 2014 by

When black became the new black

This court mourning dress from 1781 is made from Raz de Saint-Maur, a fabric favored for the occasion because, unlike satin, it was non-reflective. (From The Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

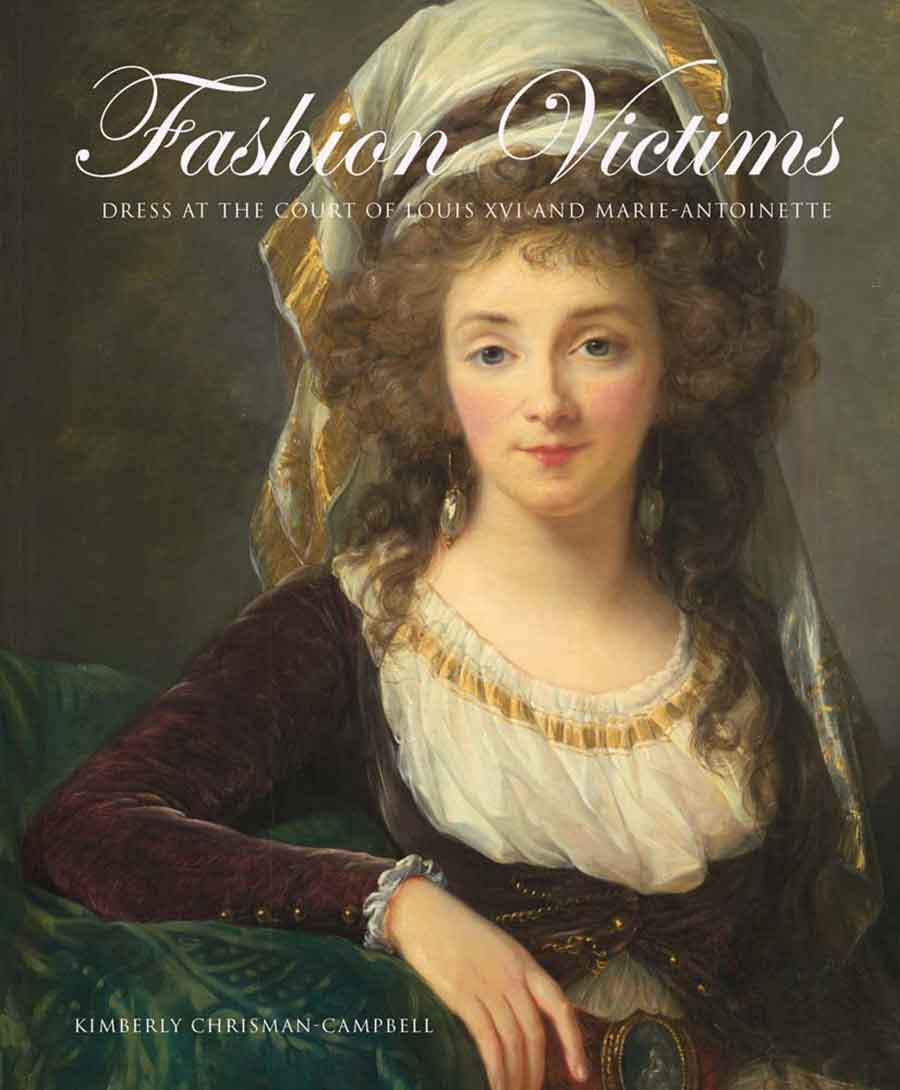

The death of France's Louis XV in 1774 was good for fashion. At the time, much of Europe followed a long-established etiquette: "Mourning lasted six months for a parent, four and a half months for a grandparent, and two months for a sibling," writes independent researcher and former Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in French Art at The Huntington Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell. Her book, Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, published by Yale University Press, is due out in April 2015.

The loss of a king who had reigned for nearly 60 years called for something altogether different, especially since it coincided with the coronation of an attractive young couple—Louis XVI and his wife, Marie-Antoinette. "A plethora of new mourning fashions and hairstyles appeared," writes Chrisman-Campbell, "their evocative names commemorating the late king or honoring the new one."

Also new was the embrace of black clothing as everyday wear, writes Chrisman-Campbell, thanks in part to fashion advisers called marchandes de modes, a term that translates best to "fashion merchants." Perhaps the best-known fashion merchant was Marie-Antoinette's dressmaker Marie-Jeanne "Rose" Bertin. She nurtured the queen's hunger for fashion, and in so doing helped the young queen become a petite-maîtresse or "fashion victim"—someone who values fashion for fashion's sake alone. So enamored was the queen of fashion's endless possibilities, she was rumored to have had a different pattern of Scottish linen undergarments for each day of the year.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell's book describes one of the most extravagant periods in the history of fashion: the reign of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette.

"Fashion victim is a very contemporary term for a very old idea," explains Chrisman-Campbell. Of course, victimization can work on multiple levels. A 1783 portrait by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun depicts the queen in a white muslin gown that became known as the gown à la reine. Marie-Antoinette's apparent preference for simplicity over sophistication backfired, subjecting her to criticism in the very fashion magazines she so revered. She couldn't win.

By the time the revolution took hold, dressmakers, tailors, and shoemakers associated with the court had to flee the country, and Chrisman-Campbell follows them to other parts of Europe and to America, adding a new chapter to the history of the French Revolution. Marie-Antoinette paid a high price for her supposed defiance—whether it was to the court or to those left eating the proverbial cake. The people ransacked and destroyed her wardrobe.

"Not a single outfit survived," says Chrisman-Campbell. "We can't just open up a closet to see her wardrobe. I had to go back to documents and pictures to reconstruct it."