Negotiating Religious Difference in 18th-Century Kilkenny

Posted on Wed., March 2, 2022 by

Perhaps by John Clarendon Smith (British, 1778–1810), Kilkenny, undated, wash over pencil, unfinished, 9 3/4 x 16 1/8 in. (24.8 x 41 cm). Gilbert Davis Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. The large church building in the background is St. Canice’s Cathedral, built in the 13th century; the round tower next to it is even older, dating to the ninth century. Both are still standing today.

Edmund Madden, son of local proprietors Matthew and Judith Madden, was a joiner or cabinetmaker who worked on municipal projects, such as the 1782 construction of St. Kieran’s College, Ireland’s first Catholic academy and seminary. He was paid more than 10 pounds by Parliament for his work on “Sash Lines and Pullies”—perhaps hinting at his skill in fashioning windows.

The book he had purchased was An Exposition of the Doctrine of the Catholic Church, an English translation of the ninth edition of a treatise by the famed French bishop Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627–1704). The book was printed in London in 1686 by Henry Hills, a stationer with connections to the court of King James II.

What drew the young carpenter to a 100-year-old book? A book written by a long-dead Frenchman and translated for an English readership of a markedly different place and time? And what did Madden make of it—if, indeed, he read the book at all?

These were the questions that I faced upon finding Madden’s copy of the Exposition in The Huntington’s collections. I had been researching Bossuet’s reception in late 17th-century England, a world in which the Exposition played an outsized role, especially in debates over King James II’s efforts to repeal the Test Acts. Those acts were a set of penal laws that denied public office to Catholics and dissenters from the Anglican church unless they were willing to affirm Anglican doctrine by taking an Oath of Allegiance, the so-called “test.”

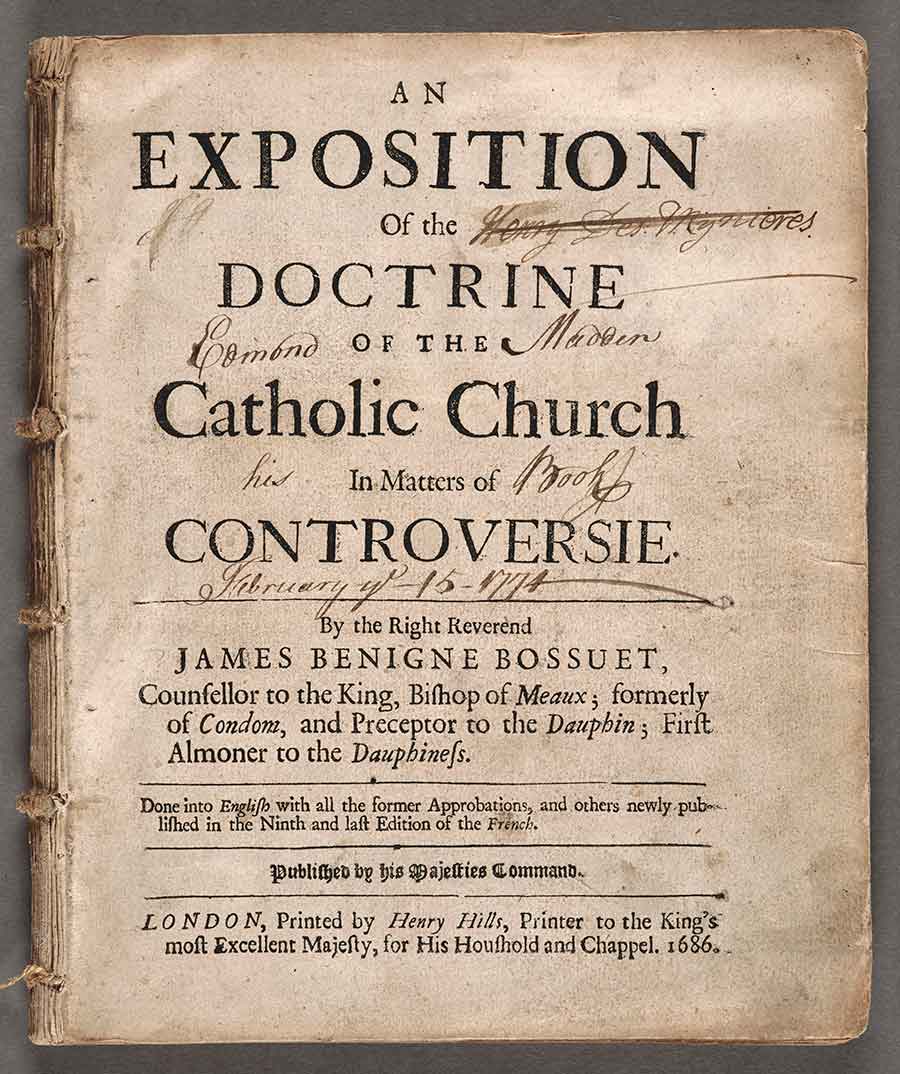

Title page of An Exposition of the Doctrine of the Catholic Church, an English translation of a theological treatise by the French bishop Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627–1704), printed in London in 1686 by Henry Hills. In 1774, Edmund Madden, a carpenter from Kilkenny, Ireland, crossed out the name of a clergyman, “Henry des: Mynieres,” who had previously owned the book. Des Mynieres was a Protestant clergyman who served in Church of Ireland parishes adjacent to Kilkenny from 1737 until his death in 1753. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

But this was not the world in which Madden, a century later, collected his copy of Bossuet’s Exposition. Indeed, when I came upon his copy, I had not yet found much evidence of engagement with Bossuet’s theological ideas in the decades following the bishop’s death in 1704—and certainly no engagement from readers outside the ministry or the academy. So, I set out to see what I could discover about Madden and his book.

Bossuet’s Exposition traveled quite a distance from Hills’ printing house in London to Kilkenny in southern Ireland, but it is not entirely surprising to find such a volume circulating in the secondhand market of this provincial town. Kilkenny had been a center of learning since its foundation as a monastic settlement in the sixth century and was an important setting for Anglo-Irish political dramas of the 17th and 18th centuries. It served as home to the Irish Catholic Confederation during the 1640s, as host to a Papal Nuncio in 1644–45, as the site of a siege by Oliver Cromwell in 1649–50, and as refuge for King James II following the Williamite invasion in 1688–89. Along with its marketplace for secondhand books, the city had one of Ireland’s most prolific print operations, a widely circulated newspaper, and quite a number of schools.

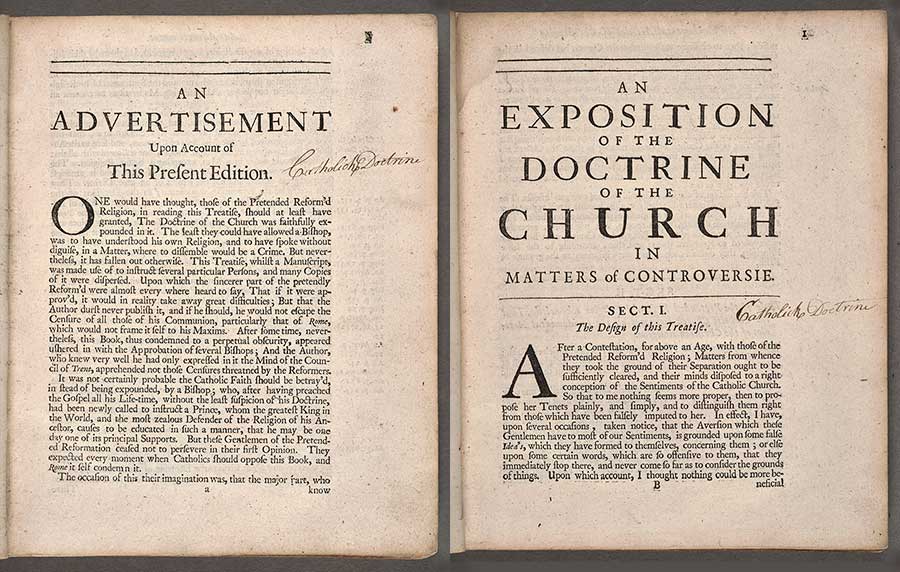

The academic character of Kilkenny can explain the presence of a copy of Bossuet’s Exposition in the marketplace, but that leaves the question of why a local carpenter would purchase the book. The copy itself provides few clues of Madden’s engagement: Only twice did he add annotations to the text, both times writing the words “Catholick Doctrine” at the outset of a new section of the Exposition. Although hardly proof of sustained reading, these markings nevertheless suggest that Madden viewed his book as a sort of index of doctrine, a fixed marker in the shifting landscape of Ireland’s ecclesiastical politics. And, as I soon discovered, such a marker would have been particularly useful for Madden.

His father, Matthew, appears to have been a Protestant—or, at the very least, a conforming Catholic—but after he died on May 2, 1774, the Madden family became increasingly associated with Kilkenny’s Catholic society. His mother, Judith, had businesses on High Street that served a markedly Catholic clientele. His sister, Mary Ann, married Louis Doly, a French traiteur who had settled in Kilkenny. Both Madden and his brother-in-law, Doly, were active in Kilkenny’s Charitable Society and may have been involved in efforts to provide free schooling for local Catholic children.

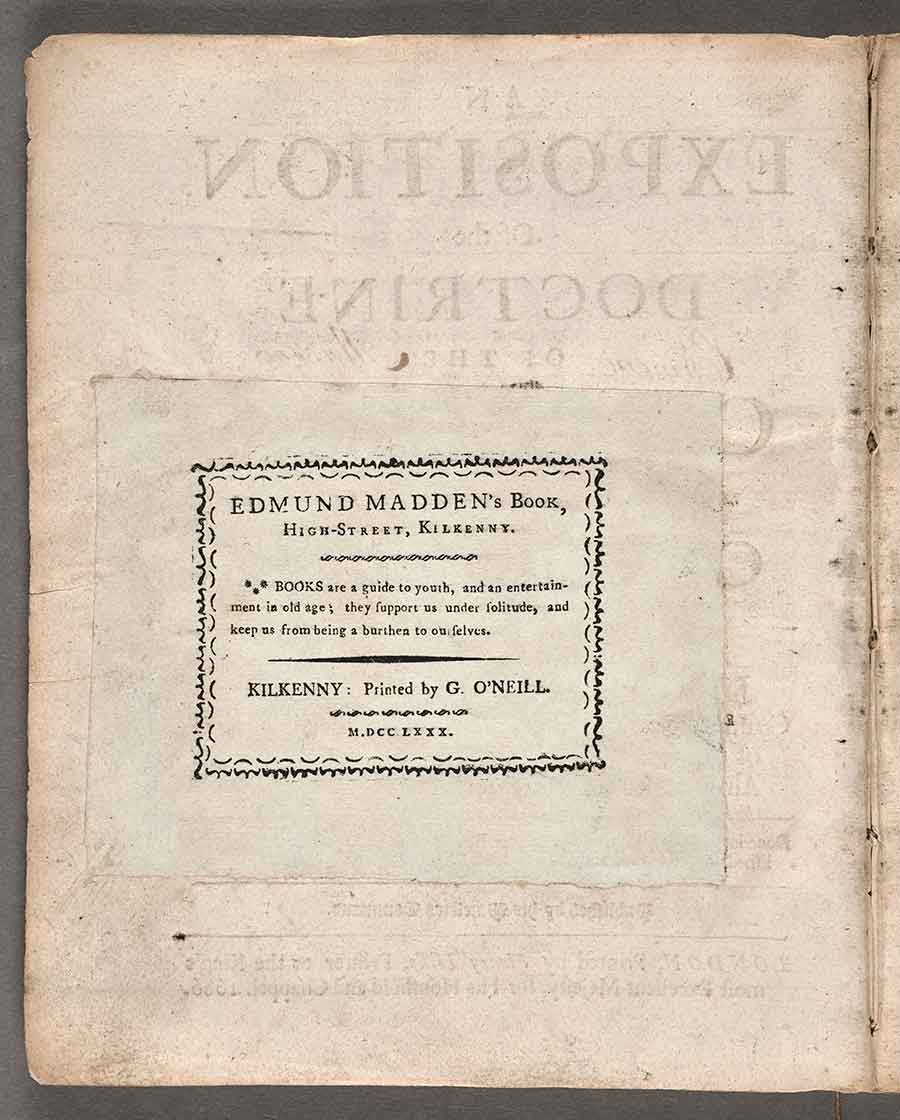

In addition to writing his name on the title page of his copy of An Exposition of the Doctrine of the Catholic Church, Madden later glued a book label on the title page’s verso. His label includes a date; an address, “High-Street, Kilkenny”; a printer, “G. O’Neill”; and an epigraph. The epigraph on Madden’s book label has been frequently misattributed but originates from Jeremey Collier’s essay “Of the Entertainment of Books” from the second part of his Miscellanies upon moral subjects (London, 1695). Collier was a contemporary of Bossuet, and they joined together in a campaign against the theater in the 1690s. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Madden had grown up in a household—indeed, in a city—where Catholics and Protestants mixed, where doctrine and practice were at once fluid and firmly taken up. Perhaps he turned to the Exposition to help him sort out the implications of religious choice—the private and public, theological and political dimensions of his faith. Just months before his father was to die, as he was entering into adult life, Madden purchased a text that addressed the differences between Catholic and Protestant theology—between the theology of his mother and that of his father.

I’ll confess that I had hoped for proof of the young Irishman poring over the subtle points and turns of Bossuet’s argument. But it is also important to recognize that acts of collecting, cataloging with a purpose, and organizing books by idea are themselves important modes of engagement. They are ways of making and marking knowledge that are part of our daily lives.

For his part, Madden would soon have new occasion to put this knowledge to use.

On Sept. 6, 1781, Madden married Jane Comerford, the daughter of a prominent Catholic family. Given the religious backgrounds of both families, I was surprised to find that their marriage license lists them as “Protestants.”

But here the story of Madden’s engagement with Bossuet comes around on itself, tying the Irishman back to Bossuet’s early English readers. Kilkenny in the 18th century, like London in the 1680s, was the site of a campaign to repeal the Test Acts, which had continued to bar confessing Catholics from public office. Just as Madden was purchasing his Bossuet, leaders in Kilkenny’s Catholic community were encouraging their parishioners to embrace a new Oath of Allegiance. In a major victory for Irish Catholics, the rigid doctrinal language of the previous Oath of Allegiance had been softened so that Catholics might take the new oath without scruple and so pass the “test” and enjoy full civil rights. By marrying as Protestants, the Maddens chose these benefits over a formal avowal of their Catholic faith. They chose to avoid the penalties of the Test Acts by conforming to the Oath of Allegiance.

Madden may have used these notes, which appear on the “Advertisement” to the ninth edition of An Exposition of the Doctrine of the Catholic Church and on the first page of the treatise itself, as part of a system for keeping track of titles as he paged through his collection of quarto pamphlets. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The psychological toll of being forced to make such decisions—in public and in private—was surely immense. In much the manner that political allegiances shape our relationships, our social and economic decision-making, our modes of expression, indeed the very way we move through our own world, so religious allegiances and convictions were central to the experience of those living in 18th-century Kilkenny. Perhaps, then, Bossuet’s Exposition, with its catalog of the similarities between Catholic and Protestant doctrine, though written more than 100 years earlier, gave some solace, companionship, and guidance to at least one woman and one man from Kilkenny, at a time when religious and political conflict was again tipping toward civil war.

Jonathan Koch is a postdoctoral instructor in humanities and social sciences at Caltech and a fellow in the 2020–22 Caltech Huntington Humanities Collaboration.