A Place at the Nayarit

Posted on Mon., May 16, 2022 by

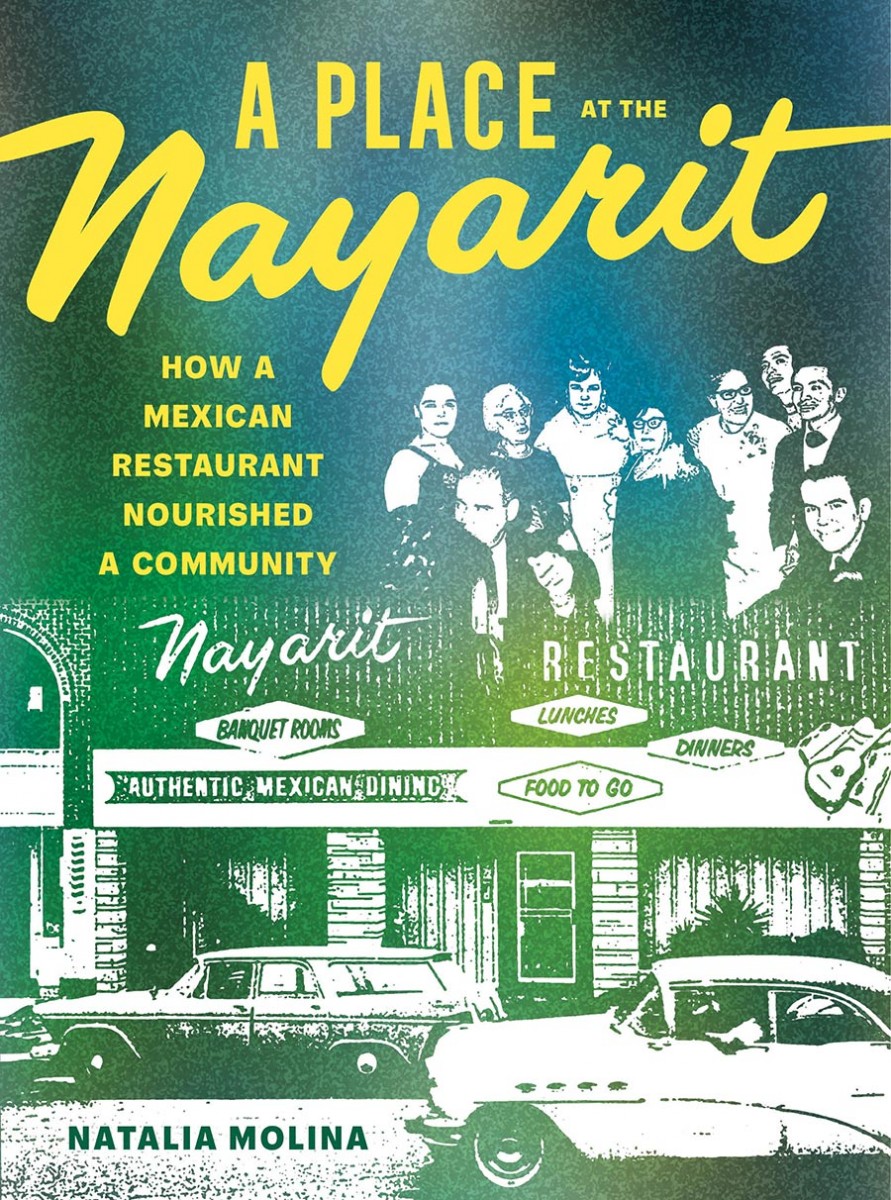

Cover of A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community (University of California Press, 2022).

Natalia Molina grew up in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Echo Park and spent evenings at the Mexican restaurant her mother owned, the Nayarit, a local landmark that her grandmother founded in 1951. Beloved for its fresh, traditionally prepared Mexican food, it drew a broad clientele, including restaurant workers from across the city and Hollywood stars.

Today, Molina is a distinguished professor of American studies and ethnicity at USC, a 2020 MacArthur fellow, and a 2020–21 National Endowment for the Humanities fellow at The Huntington. She also serves on The Huntington’s Board of Governors.

In her most recent book, A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community (University of California Press, 2022), Molina argues that the Nayarit served as a place where ethnic Mexicans and other Latinx LA residents could step into the fullness of their lives, nourishing themselves and one another. Molina received a short-term Huntington fellowship to conduct research on the book. What follows is an excerpt from the book’s introduction.

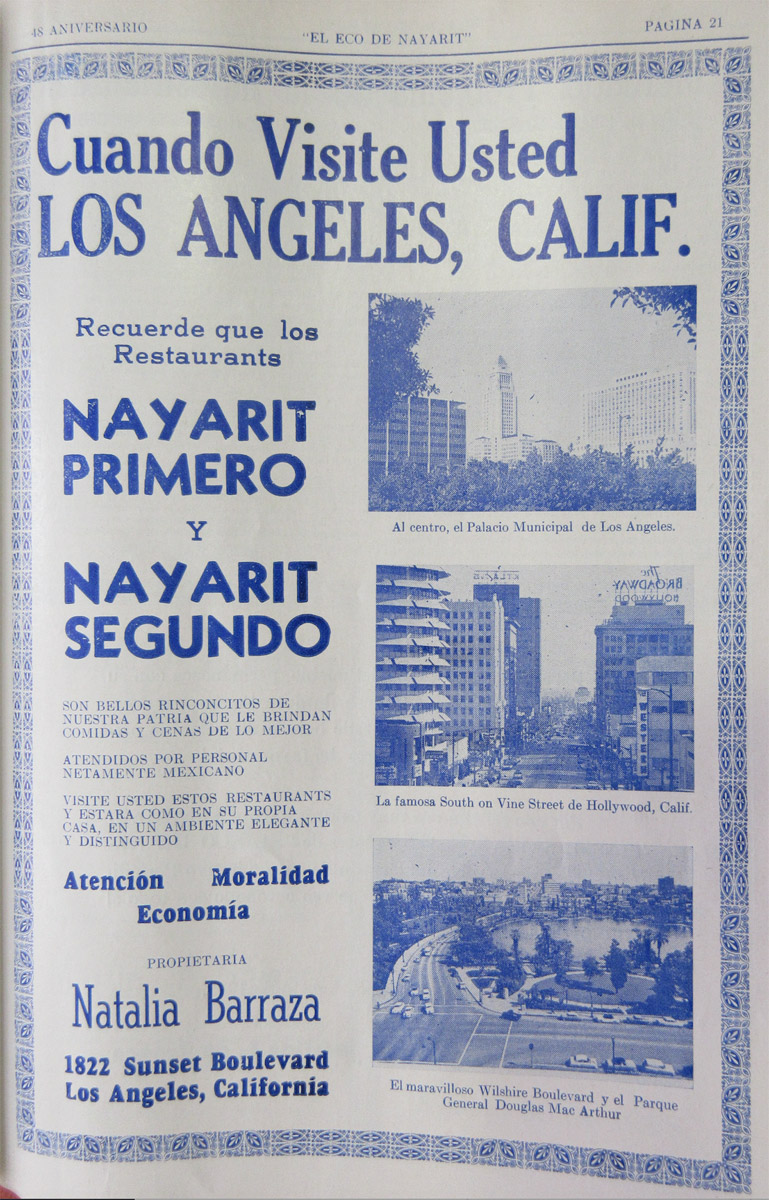

In 1965, Natalia Barraza placed a full-page advertisement in her hometown newspaper, El Eco de Nayarit. She wanted to spread the word about her two restaurants, the Nayarit and Nayarit II, where customers could count on excellent service and delicious, freshly prepared food. They would just need to travel some thirteen hundred miles, to Los Angeles, where the restaurants were located.

Placemakers: a celebration at the Nayarit, April 1968. Clockwise from top left: María Perea (the author’s mother); unknown woman; Ofelia Encinas (customer); Natalia Barraza, founder and owner of the Nayarit; María del Rosario (“Chayo”) Díaz Cueva; Pedro Cueva; Salvador (“Chavo”) Barrajas; Ramón Barragan; Ramón’s sister Dolores (“Lola”) Barragan (in profile); unknown woman and man. Photograph provided by María Perea Molina .

I saw the ad decades later, when I paged through leather-bound volumes of old issues of El Eco at the Hemeroteca Nacional de México, National Newspaper Library of Mexico. As a historian of race and immigration, I wasn’t surprised to see ads for businesses like the Nayarit run by los de afuera, particularly in Los Angeles. A large number of immigrants from Nayarit had settled there, and many stayed tethered to their homeland. But the ad for the Nayarit restaurants still took me aback. It was so much bigger than the others, and—beginning “Cuando Visite Usted Los Ángeles, Calif.” (When You Visit Los Angeles, Calif.)—it seemed to promote the city itself, suggesting that the restaurants were on par with other, not-to-be-missed attractions. That took some chutzpah. So did the inclusion of Natalia Barraza’s name, in large, confident letters at the bottom of the page.

Yet the column of stock photographs running down the right-hand side of the ad would give most Angelenos pause. The top photo shows Los Angeles City Hall and the bottom one, Wilshire Boulevard along MacArthur Park—lovely municipal sites but not exactly tourist attractions. The middle photo does show the famous intersection of Hollywood and Vine, including the iconic Capitol Records Building, designed to resemble a stack of records on an autochanger, with a tower whose light blinks out the word Hollywood in Morse code. The caption, however, reveals an unfamiliarity with the area, and with the English language. “La famosa South on Vine Street de Hollywood, Calif.” it reads, neglecting to mention Hollywood Boulevard. It is not clear what “South” refers to, perhaps the direction from which the photograph was taken. Neither of the Nayarit restaurants was particularly near to or had any identification with the landmarks pictured. The larger restaurant, the Nayarit, was located between downtown and Hollywood, in Echo Park. The Nayarit II was located two miles east, on the northeast edge of downtown Los Angeles. The ad suggested that these restaurants catered to insiders but revealed that their owner was an outsider, navigating multiple cultures.

Natalia Barraza’s ad for the Nayarit in El Eco, August 1965.

She was poised to help others do the same. “NAYARIT PRIMERO Y NAYARIT SEGUNDO,” the text proclaims, are “bellos rinconcitos de nuestra patria que le brindan comidas y cenas de lo mejor atendidos por personal netamente Mexicano” (beautiful little corners of our homeland that provide the best lunches and dinners served by a clearly Mexican staff). The ad goes on to read, “visite usted estos restuarantes y estará como en su propria casa, en un ambiente elegante y distinguido” (visit these restaurants, and it will be like you are in your own home in an elegant and distinguished environment). Clearly, the ad plays on the concept of patria chica (literally, “small country”), which refers to the highly localized loyalty an immigrant has to their hometown, village, or region. By evoking the visitor’s connections to a particular home state, the restaurant would satisfy that feeling of patria chica. Mexican visitors could feel safe at the Nayarit, a space where they could speak their native tongue, be served only by fellow nationals, and escape whatever prejudice they might fear having to face in the city as a whole. Analyzing the operation and extent of those prejudices and dangers—from daily slights to large-scale terror campaigns like mass deportation—has been at the heart of my work as a historian over the past twenty years. That work has shown how thoroughly being Mexican shaped people’s access to space, including where they could live, work, worship, play, go to school, and even be buried.

I have a unique connection to the Nayarit. Natalia Barraza is my grandmother. I never met her, but I was named after her, and my mother, María, was her right-hand assistant in the business. I grew up surrounded by people who worked at the Nayarit or had been regular customers, listening, fascinated, to their stories about the restaurant and about Doña Natalia. They all spoke of her with admiration for her strength, her talent, and her generosity with relatives in Los Angeles and Nayarit. She had come to the United States on her own, on the heels of the Mexican Revolution, and worked through the Great Depression. She could not write, read, or speak English, but she ran a successful business, sponsored dozens of immigrants—many of them single women and gay men—gave them jobs and places to stay, and encouraged them to venture out and explore L.A. Sometimes she would loan the women clothing and jewelry for the occasion. No one, however, described her as a warm person. She was formidable and removed. My mother never called her “mom”—only the more formal “my mother”—and everyone else referred to her with a title: Tía (Aunt) Natalia, Doña Barraza, or Doña Natalia. “Doña” conveys a bit more respect and a higher rank than “Mrs.” or “Miss,” and it captures my own sense of my grandmother. I think and write about her as Doña Natalia.

Doña Natalia with her adopted children, Carlos and María (the author’s mother). Photograph provided by María Perea Molina.

Over the course of her life, Doña Natalia started three restaurants called the Nayarit. The earliest, which I call the original Nayarit, was at 421 Sunset Boulevard, between Broadway and Spring Streets, and was in operation from 1943 to around 1952. What the ad in El Eco refers to as the “Nayarit Primero” was founded in 1951 at 1822 Sunset Boulevard. In 1964, she opened what the ad calls the “Nayarit Segundo,” and what some people called the “little Nayarit,” at 640 N. Spring Street, around the corner from where the original Nayarit had stood. It catered mainly to downtown office workers and closed in 1968. But it was the main location, in Echo Park on Sunset, that I grew up hearing about. It was the largest and the longest-lasting, and the place where Doña Natalia spent most of her waking hours. My cousin, Doña Natalia’s granddaughter, told me that when her family visited our grandmother, they rarely did so at her home. Instead, they came to the restaurant. The Nayarit was the center of the community Doña Natalia helped build, and she was there seven days a week, ensuring it ran smoothly.

At the time, Echo Park was something of a cultural crossroads, a haven for gays, liberal whites, ethnic Mexicans (referring to both Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants), and an abundance of other immigrants. Living alongside one another made it easier for people to develop comfort with those outside their racial and ethnic communities, and while the Nayarit’s largest customer base was ethnic Mexicans, it catered to a diverse clientele and became a fixture in the community. Alexis McSweyn, whose ethnic Mexican parents had begun taking her to the Nayarit when she was nine, told me years later that she was shocked if she ever met someone in the neighborhood who hadn’t been to the Nayarit: “You’d think, ‘What?!’ The Nayarit was Echo Park.”

Doña Natalia died in 1969, two years before I was born. María ran the business for a few more years while caring for me and my older brother, David (born in 1965), but sold the lease in 1976 to new owners who kept the old name. I have scant memories of the Nayarit from those first few years of my life, but I grew up in the neighborhood it fed, in a home Doña Natalia purchased, in a place she helped make. By the time I was five years old, I felt perfectly safe venturing out from the restaurant where my mother was busy with work to walk a couple of doors down to the corner to get a Cuban pastelito at El Carmelo Bakery. The regulars knew one another, had known my grandmother, knew my mother, and knew me. The neighborhood was an extension of home. A number of former Nayarit employees went on to open their own restaurants nearby, including Barragan’s and La Villa Taxco and El Conquistador and El Chavo, which were havens for gay clientele. When my family and I would eat at these restaurants, we were also visiting fictive kin. I played with the children of Nayarit workers and customers, attended christenings and weddings and funerals of family and friends with ties to the restaurant, and learned from them to be curious about the wider world. Even now, when we go out together, they are eager to see how restaurants approach decor, menu planning, plating, and service. They go to all sorts of restaurants, all across the city. To get more information about both restaurants and the experiences of workers, they tend to find a Latinx immigrant server or busboy whom they pepper with questions. What is in the mole that gives it that distinctive taste? Where are you from? Do they treat you well here? Sometimes they end up getting off-the-menu extras, like salsas made for staff meals in the back, shuttled to our table.

Facade of the original Nayarit restaurant, which closed around 1953. Left to right: Doña Natalia’s friend Cecilia Torres; Carlos Peres (Doña Natalia’s son); Ramón Barragan. Photograph provided by María Perea Molina.

The Nayarit has taken on renewed prominence in my life over the past few years, as I see the ways Echo Park is changing. When I attended college at UCLA in the early 1990s, I grew accustomed to classmates dismissing my neighborhood as a “bad part of town.” One wrong turn on the way to a Dodgers game, they would say, and you risked ending up in the barrio. If I told them that was my ’hood, they would fall into uncomfortable silence. I knew their viewpoints were shaped by a lifetime of seeing barrios and ghettos depicted as dangerous places inhabited by dangerous people. They had been given no historical understanding of how these places came to be, or what they meant to the people who lived there. In the ensuing years, though, Echo Park has undergone remarkable levels of gentrification. Hipsters have replaced homeboys, high-end coffee shops have pushed out mercaditos—and some of the “pioneering” new businesses have now been priced out themselves. Echo Park is no longer the subject of urban decline but of urban renewal. Ironically, it’s the diversity of the neighborhood, its “authenticity,” that makes it attractive, and yet this is what is most threatened as those with higher incomes move in. Similar changes are afoot in the traditionally Latinx neighborhoods of Boyle Heights and Highland Park and in cities across the country.

Echo Park and neighbohoods like it are often perceived as lacking a rich history, as though nothing much happened before the arrival of wealthier newcomers. People who have built their lives in such places know otherwise. So as the neighborhood has become less and less familiar to me, I kept circling back to this place, and these people, because I recognized that they get at something important, something that history books, popular media, and landmark timelines rarely capture: how marginalized people can create their own places in ways that reclaim dignitiy, create social cohesion, and foster mutual care. This book is meant to call attention to such creative actions, to the ways communities can define places on their own terms, sometimes as a direct challenge to the existing environment and sometimes as an alternative.

Natalia Molina stands in front of the Nayarit, a restaurant founded by her grandmother, Natalia Barraza, in 1951 at 1822 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles. Today, the building is home to the Echo, a music venue and nightclub. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez.

To read more, you can purchase A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community in person or online from the Huntington Store.

Natalia Molina is also the author of the award-winning books How Race Is Made in America: Immigration, Citizenship, and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts (University of California Press, 2014) and Fit to Be Citizens? Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879–1939 (University of California Press, 2006).