View Master

Posted on Sat., Oct. 25, 2014 by

A photographer immerses himself in The Huntington's bonsai and penjing collections

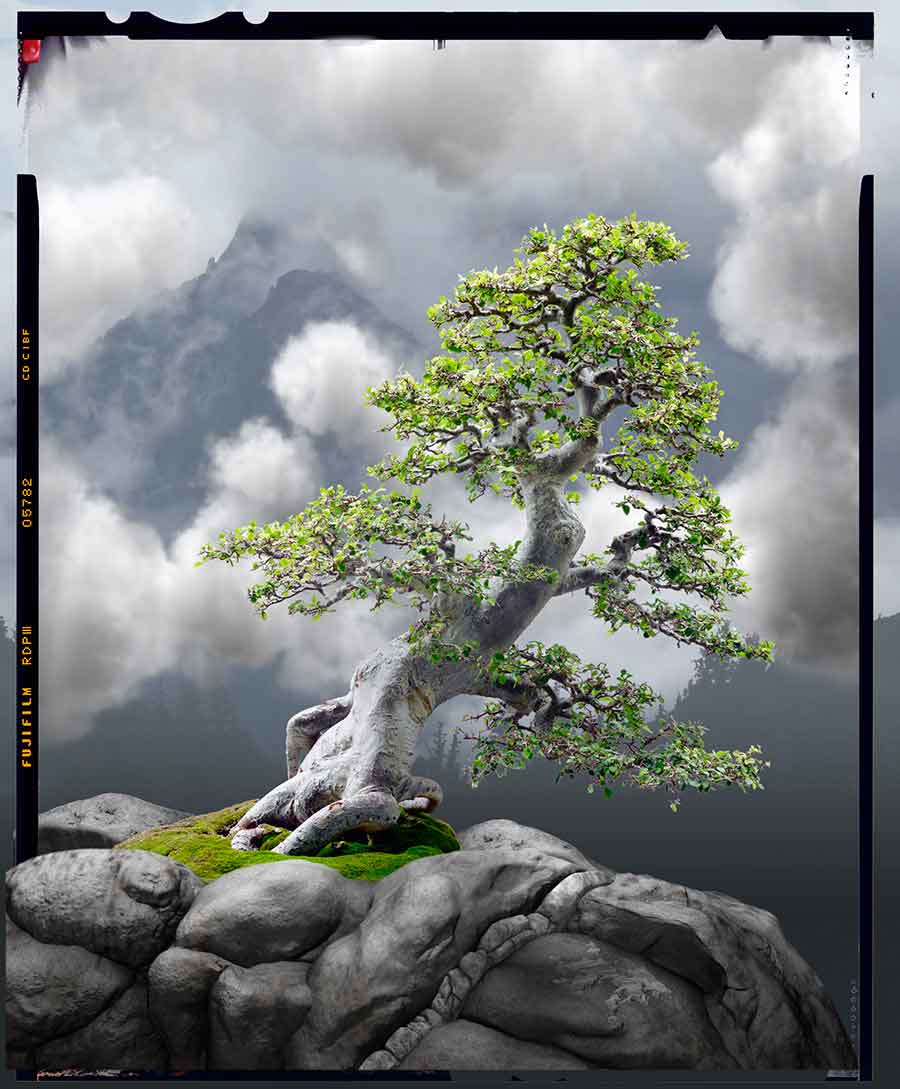

During a one-month fellowship at The Huntington, Hilyard shot this miniature Chinese elm tree, pictured left, a type of penjing in the Chinese garden. Then he used 3-D software to add rocks and clouds, tricking the eye into thinking it's full-sized.

Photographer Stephen Hilyard does things big. In the summer of 2007, he donned a dry suit and jumped into a lake in Þingvellir (in English, Thingvellir), in southwestern Iceland. He wanted to capture scened of underwater "landscapes," and the lake's Silfra rift was known for its spectacular geologic formations. In exchange for withstanding temperatures hovering around 33 degrees Fahrenheit, Hilyard would be assured exceptional visibility.

For Hilyard, the rugged terrain was evocative of Mount Everest, K2, and other magnificent peaks that have taken the lives of countless climbers willing to risk death in pursuit of dominance, beauty, or what 18th-century explorers called the "sublime," when beauty and danger converge to create the profound.

Although Hilyard admits he fell victim to the pull of the sublime in traveling to the frigid Silfra, his real immersion didn't begin until he came up for air to process his digital images.

"A lot of my work involves images of nature that first appear relatively straightforward as picturesque landscape," he says of his larger-than-life subjects, including mountains, waves, and waterfalls. But look closer and you'll notice that he alters the images digitally in subtle ways, making them "a little bit too perfect" or "slightly uncanny." Rapture of the Deep is a series of eight large prints (measuring about three by four feet), each named after a British climber and the place and date where he lost his life. In Dougal, Leysin 1977 (see detail below and full photograph further below), it takes viewers a moment to realize they're not looking at a mountain climber high on a peak but rather a crafted image of a figure superimposed on an underwater "mountain-scape."

At the left is a detail from the photographer's Rapture series. At right, the photographer turns his lens on the Japanese Garden's bonsai court. Photograph by Kate Lain.

"The pictures are not actually 'real,' but I want them to represent an ideal," he explains. "They're failing slightly. There's a clue in there somewhere." (The figures are the photographer himself, dressed in 1970s mountaineering gear.)

Hilyard brought this combination of adventure and artistry to The Huntington's Japanese Garden in 2012, shortly after the garden's reopening following a year-long restoration. He looked past the rolling hills of the garden's most iconic vista to the tiny wonders of bonsai exhibited in two courtyards on the western plateau. On display are just shy of 100 bonsai from The Huntington's collection of more than 500, including miniature Japanese black pine, maple, and juniper, among other species. He also shot penjing, the Chinese precursor to bonsai, in the Chinese garden, such as the photograph that opens this article. Hilyard, digital arts professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, set out to produce his prints as large-format 3-D photographs.

"Bonsai have been trained to represent an ideal," says Hilyard, who claims a kind of kinship with bonsai masters, who spend decades manipulating and sculpting their subjects. "Bonsai are heavily codified with various styles and requirements, and that speaks to the core of what my art is about: a belief that our experience of everything is culturally mediated."

At Wisconsin, Hilyard teaches courses on 3-D digital modeling and animation but also carves out time for his own art. Born in Southhampton, England, he has held on to a slight accent in the 20-plus years he has lived in the United States. Over the years he has exhibited his work throughout the country, including exhibitions of Rapture of the Deep at the American-Scandinavian Foundation in New York City as well as the Platform Gallery in Seattle, his home base for shows. In another show, "The Ends of the Earth," Hilyard exhibited five views of mountain landscapes, based on scenes from Iceland. He has also traveled to Africa, Australia, and the Arctic in pursuit of his craft.

Compared to scuba diving in Iceland, there was something downright tame about Hilyard's set-up in the quiet of The Huntington's Japanese Garden, where his greatest challenge was to work quickly from dawn to about 10:30 a.m., when the June gloom gave way to hazy midday light.

"I did all of my shooting under the marine layer, and the lighting under the clouds was really great," he says. "It's a really beautiful soft light—and it's consistent and flat, which is what I needed for the 3-D effect."

In Dougal, Leysin 1977, artist Stephen Hilyard pays tribute to Scottish mountaineer Dougal Haston, who died trying to deliberately out-ski an avalanche on the notorious slopes above Leysin, Switzerland. Look closely and you'll see the figure is not up high, but superimposed on an underwater "mountain-scape."

In his khaki shirt, pants, and vest, Hilyard cuts a figure of someone at home in nature, whether it be hiking to faraway mountains or waterfalls or tracking shadows in a Southern California garden. But he never loses sight of the real adventure in this process—what he does after a shoot in the darkroom and on the computer screen. When his digital camera didn't give him the resolution he was after, he shot the bonsai on film and then ran the prints through a drum scanner in order to produce sheets as large as 36 inches wide. Although he's been honing his craft for years, he had never jumped into large-format 3-D photography until this project.

Hilyard describes himself as a collector—of techniques, images, stories. Before bonsai or underwater diving he had dabbled in needlepoint, quilting, bookmaking, and wood carving.

"I carry these ideas around—sometimes for decades—until I bump up against something else," he says, "and the combination then becomes a kernel of an idea for a piece."

Long before he hit on bonsai as a subject, he came across the technique for making 3-D photographs. About 15 years ago he was living in Oakland and was enamored of a small Berkeley gallery showing large-format 3-D images of various landscapes, including the Everglades.

"The sensual experience and pleasure of looking at that kind of imagery really stuck with me," he recalls. "So that went into the bag, and I carried it around for years as something that I was interested in." The fascination with 3-D also stems from an interest in the 19th-century practice of stereography, but stereographs are typically quite small, and Hilyard was interested in big. He liked the effect of the 10-inch-wide 3-D photos in the Berkeley show and wondered if he could push them to an even larger scale.

Meanwhile, Hilyard was grooming a separate interest in miniaturization, and something clicked when he came to The Huntington back in 2008 and wandered through the bonsai collection.

"It made perfect sense to combine these two things," he says, pulling bonsai and large-format 3-D photography into the broader category he calls "mediation." "Both of these examples are perfections of simulations of real experiences, which are in fact not real," he continues, veering a bit into academic speak. "In fact, they are hyper-real, and that's where part of the sensual experience comes from, I think."

He hoped his blending of the small art form of bonsai with large-format 3-D photography would allow viewers to experience bonsai in a whole new context—not from above but from inside the landscapes that bonsai masters have been crafting for centuries. The "uncanny" element in this project would be his manipulation of scale.

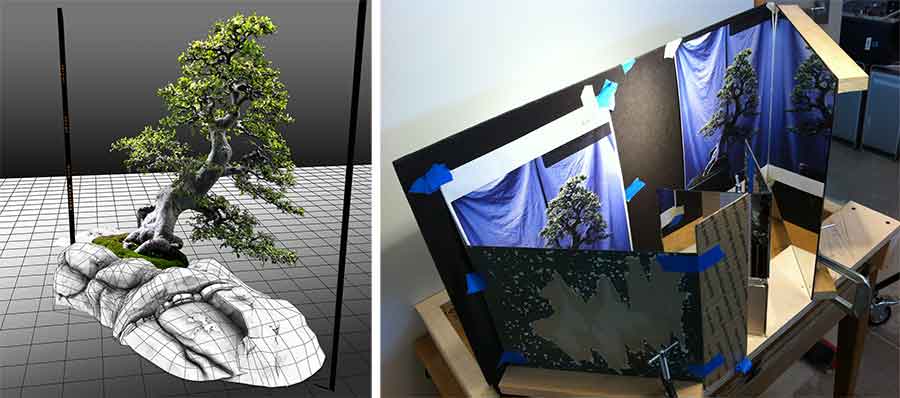

Left: Hilyard spent two years manipulating photos of bonsai and penjing. Here is one step in the creation of the final image that opens this article. Right: The photographer created a prototype-viewing device big enough to see the large prints in 3-D. The device currently measures three feet by two feet by 20 inches deep, though he may go larger if he finds the quality improves. Here, low-quality prints stand in for the real thing, allowing him to tweak the proportions and angles of the parts.

Like most of us, Hilyard comes to bonsai as an observer, as someone who knows he is being manipulated by the bonsai masters, but he then tries to push that verisimilitude even further. Viewers of his photos will first think they are looking at full-sized trees. Like his mountain climbers of the deep, his bonsai contain subtle clues that something is "off"—perhaps the proportion of the leaves to the tree or the texture of the bark. The 3-D effect magnifies that feeling of perfection.

Yet another item in Hilyard's kit bag is a story about the history of penjing, a Chinese precursor to bonsai, which he admits is more origin myth than fact. "I often work with stories that are deliberately fictionalized or bowdlerized in some way," he says, in part to acknowledge the thread of manipulation in all his pursuits.

As Hilyard retells it, Qin emperor Shi Huangdi (260-210 BC), who ruled from 221 to 210 BC, wanted to map his entire empire, so he sent out emissaries to create miniature landscapes of each region. The penjing were then displayed on a map of the empire carved into the floor of a courtyard in the palace.

"So Shi Huangdi's miniature garden really struck a chord with me, in part because of the way miniaturization includes a kind of god-like view or power," says Hilyard. "Whether it's a train set, fish tank, or bonsai tree, you have this kind of god-like view of anything that has been miniaturized, just like the emperor did. You can float over it and look at it from any angle."

Hilyard has not created worlds from above but from within. Talk to Hilyard long enough and he'll hit on the ultimate goal of his art, which is the same as that unspoken prize supposedly found at the end of those dangerous mountain climbs—the sublime.

"There's a lot of talk about the sublime in contemporary art," he says. "The irony is that when someone approaches the so-called profound, he or she is likely preoccupied with worldly things—How am I going to get down from here!"

"So the sublime is an ideal that we keep searching for but never actually attain," he says. "No one has ever been able to describe it, pin it down, create a formula for it, or take a picture of it, but we still believe it exists."

That, to put it simply, is the feeling he hopes to evoke in those who view his art.

The human eye is a sophisticated viewing device. See the two images blend into one by crossing your eyes and staring at the point between the two bonsai. Then relax as a single 3-D image comes into focus.

Of course, creating the sublime is just as elusive as the pursuit. Whereas the Chinese emperor had his army of penjing masters and his omniscient perch above the map of his empire, Hilyard uses light boxes, mirrors, and digital software programs. In the two years since Hilyard took his bonsai photographs, he has been methodically and painstakingly processing them for display. After taking countless pictures, he settled on about a dozen images, and from there further refined five. The small sample size is essential because he then spends countless hours masking or outlining the trees from their natural backgrounds before placing them into a virtual world in his 3-D modeling software.

Finally, the last step in mediation comes with the viewing device. In place of 3-D glasses, Hilyard has created a special contraption big enough to view his large images. These light boxes contain highly accurate front-silvered mirrors borrowed from astronomical instruments. Hilyard still has a few refinements to make to his images and to the viewing device before he's ready for the big reveal. Then when viewers peer into the boxes, they will enter—just for a moment— a land of wonder.

Matt Stevens is editor of Huntington Frontiers.