West of Slavery

Posted on Wed., May 26, 2021 by

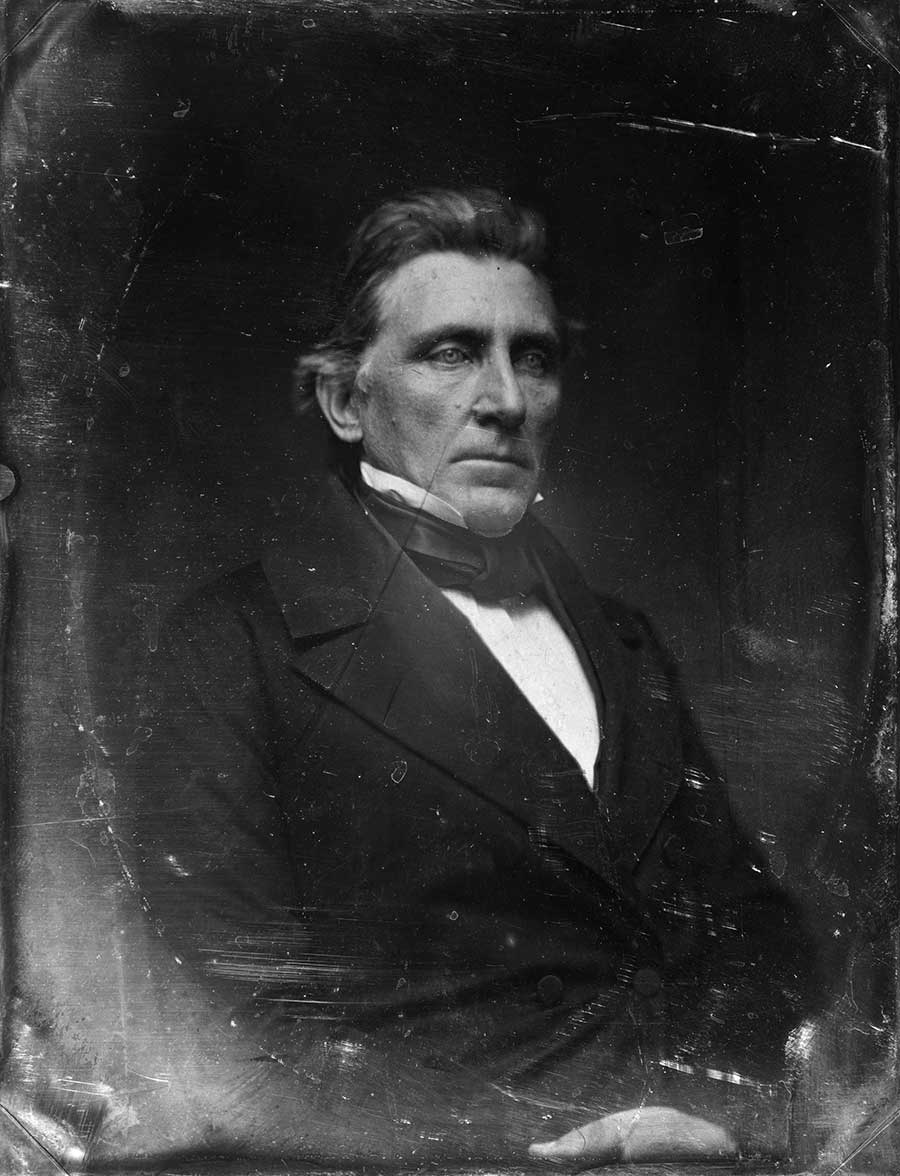

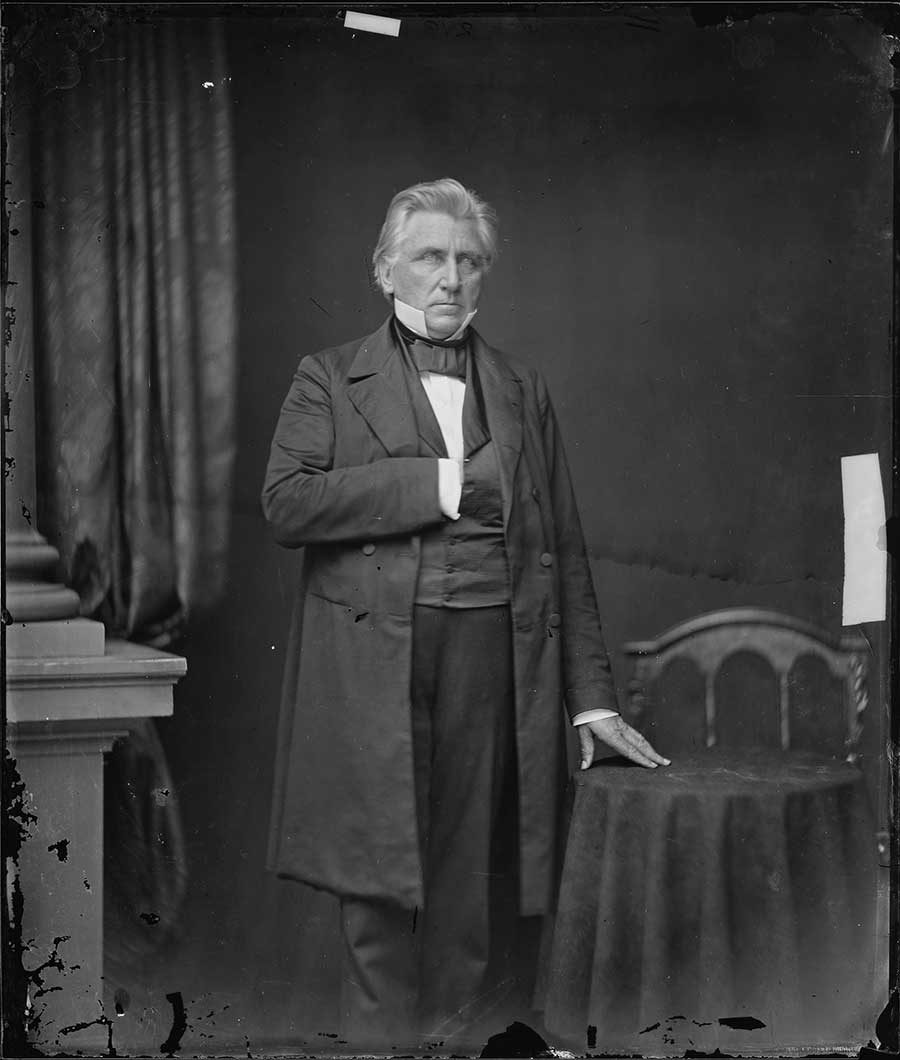

Mathew Brady (1822–1896), William M. Gwin, half-length portrait, three-quarters to the right, between ca. 1844 and ca. 1860. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

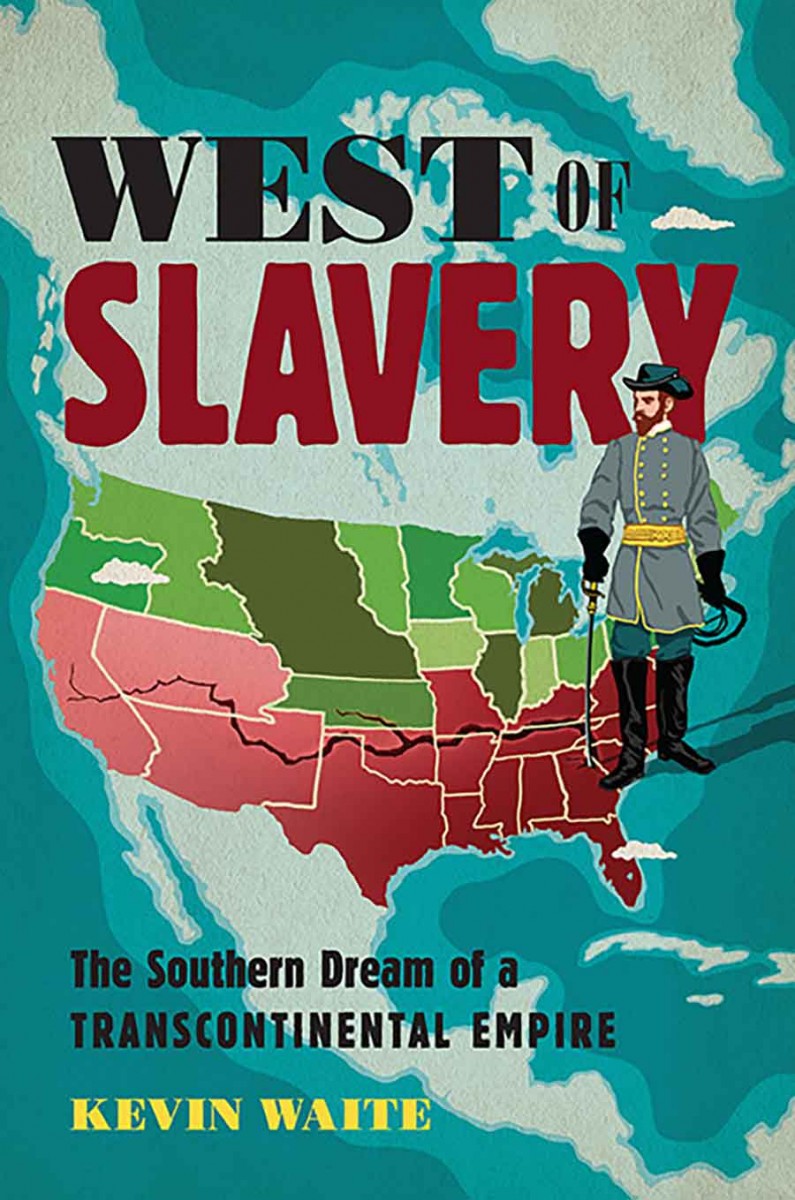

When American slaveholders looked west in the mid-19th century, they saw an empire unfolding before them. They pursued that vision through official diplomatic channels, migration, and armed conquest. By the late 1850s, slaveholders and their allies had transformed the southwestern quarter of the nation—California, New Mexico, Arizona, and parts of Utah—into a political client of the plantation states. Across this vast swath of the map, white southerners defended the institution of African American chattel slavery as well as systems of Native American bondage. In his book, West of Slavery: The Southern Dream of a Transcontinental Empire (University of North Carolina Press, 2021), Kevin Waite, assistant professor of history at Durham University in England, uncovers this surprising history of the Old South in unexpected places, far beyond the region’s cotton fields and sugar plantations.

Slaveholders’ western ambitions culminated in a coast-to-coast crisis for the Union. By 1861, the rebellion in the South inspired a series of separatist movements out West. Even after the collapse of the Confederacy, the threads connecting South and West held, undermining the radical promise of Reconstruction. Waite, using Huntington materials in part, brings to light what contemporaries recognized but historians have described only in part: The struggle over slavery played out on a transcontinental stage. In the following essay, adapted from his book, Waite focuses on William M. Gwin, a slaveholding former senator from California who fled the United States to the court of Napoleon III toward the end of the Civil War. Gwin soon convinced the emperor to throw France’s support behind a bold scheme for a renegade colony in Sonora, Mexico, from which Gwin planned to launch a second rebellion against the war-torn U.S., eventually drawing California, he hoped, into an independent Pacific republic.

As U.S. troops dug in for a prolonged siege of Petersburg, Virginia, in the winter of 1864–65, their commander contemplated a new campaign roughly 3,000 miles away. General Ulysses S. Grant looked toward northwest Mexico with growing disquiet, even as his forces prepared for the final crushing assault on the Confederate South. The object of his anxiety was a motley group of “dissatisfied spirits of California” who had congregated in an expatriate colony in Sonora, Mexico. From this colony, Grant feared an assault on the soft underbelly of California. In which case, he was prepared to respond in force, as he wrote to one of his generals. “I would not rest satisfied with simply driving the invaders onto Mexican soil,” Grant fumed, “but would pursue [them] until overtaken, and would retain possession of the territory from which the invader started until indemnity for the past and security for the future . . . was insured.”

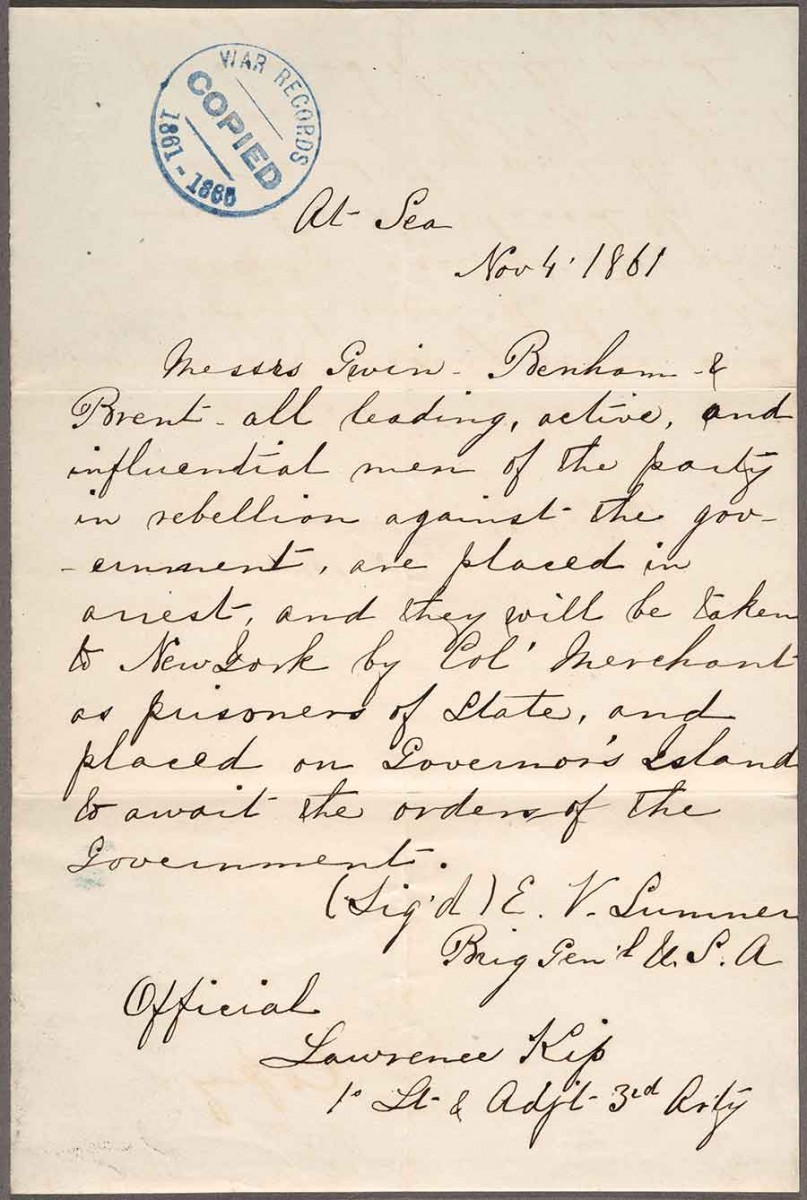

Edwin Vose Sumner (1797–1863) to Lawrence Kip, Nov. 4, 1861. This is a copy of General Sumner’s original arrest order for William Gwin, Calhoun Benham, and Joseph Lancaster Brent when they were sailing from California to Panama. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Grant, currently engaged in what would become a 292-day siege of the main Confederate army in Virginia, certainly had more pressing concerns than a ragtag group of American exiles in a far-flung Mexican colony. Why, then, did he contemplate an invasion of a sovereign foreign nation and threaten to turn his nation’s civil war into an international conflagration?

The answer to that question lies in The Huntington’s archives, where a collection of letters reveals the true story behind this little-known episode in Civil War history. Those letters put us on the trail of a California rebel who crisscrossed the Atlantic, defied U.S. authorities, and conspired with emperors—all in a wildly ambitious attempt to build an empire of his own.

***

William McKendree Gwin (1805–1885) was the most powerful man in California during the decade between the Gold Rush and the outbreak of the Civil War. Born in Tennessee, educated in Kentucky, and groomed politically in Mississippi, Gwin moved to California shortly after the discovery of gold in 1849. While most migrants streamed toward California’s mineral wealth, Gwin had come west for a different kind of prize: a seat in the U.S. Senate. He won it that same year and held the position for the rest of the decade (except for a lull between 1855–57, when the Senate seat remained vacant.)

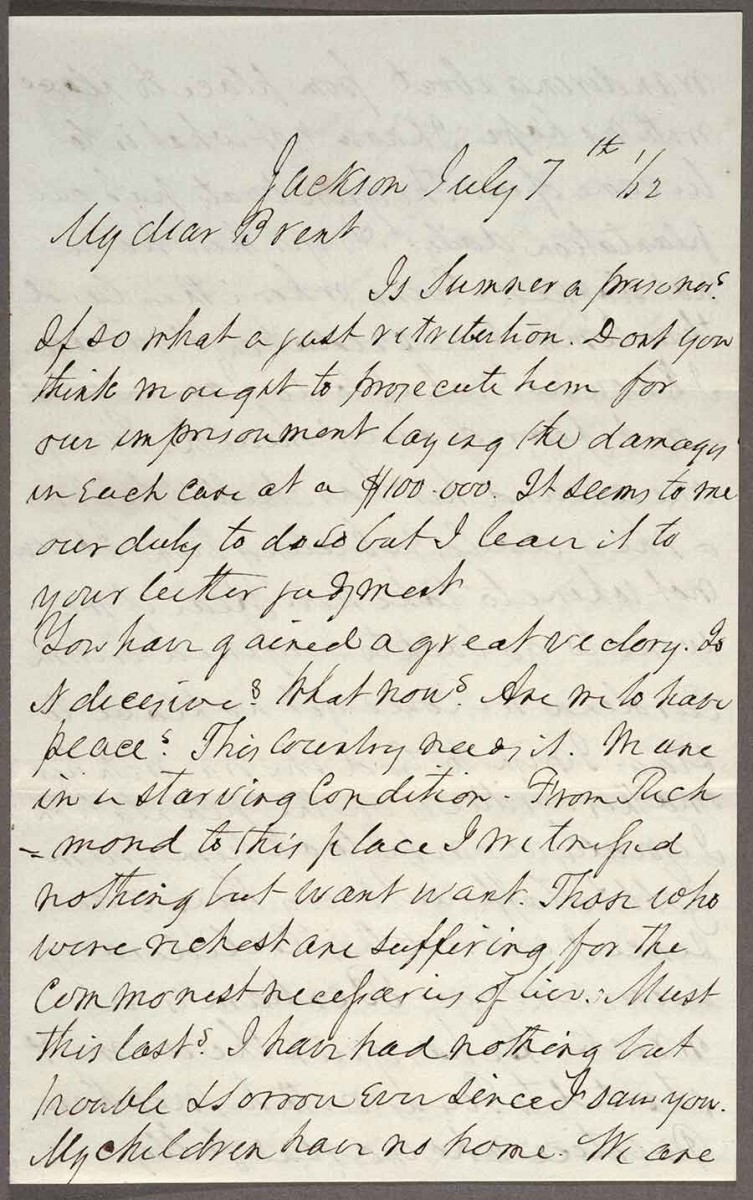

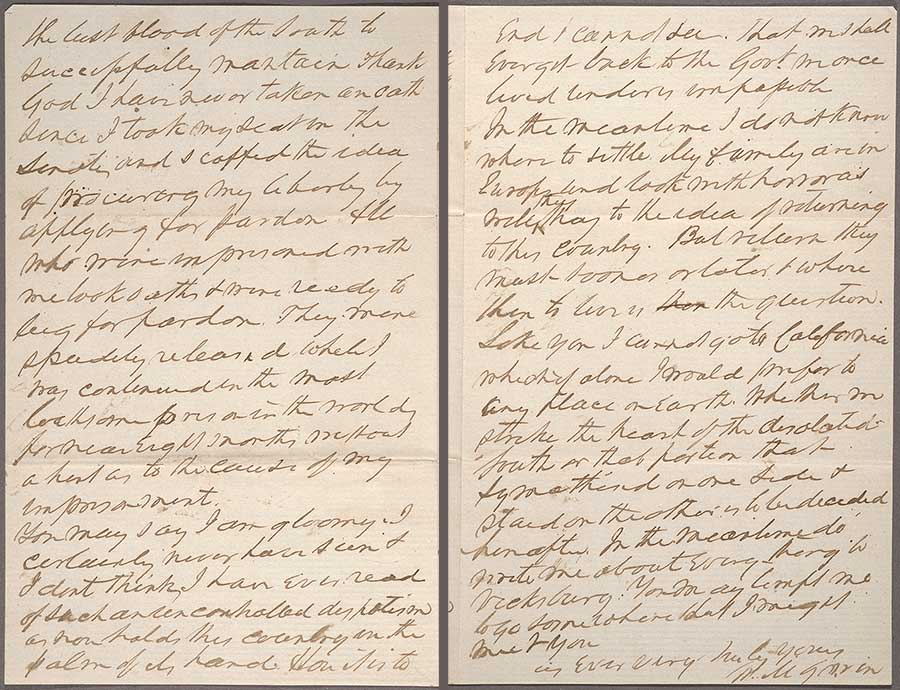

William McKendree Gwin (1805–1885) to Joseph Lancaster Brent (1826–1905), July 7, 1862, first page of a four-page letter. While in Jackson, Louisiana, Gwin writes of his life since his release from prison at Fort Lafayette in New York: “I have had nothing but trouble and sorrow ever since I saw you. My children have no home.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Although he went to Washington as a representative from a free state, Gwin’s political loyalty lay with the slaveholding South. He demanded strict discipline from his faction of the Democratic Party, known as the Chivalry, and rewarded his Southern-born allies in California with the majority of the state’s well-paying patronage positions. He also continued to own a large plantation in Mississippi and more than 200 slaves. Thanks to Gwin, California’s political leadership generally sided with the South on the major political issues of the day, such as the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Dred Scott decision. As one pioneer remarked, albeit with a touch of hyperbole, “the State of California was as much under the control of the Southern wing of the Democratic party as South Carolina, and voted in Congress for Southern interests to all intents and purposes.” It was a place, he continued, “as intensely Southern as Mississippi or any other of the fire-eating States.”

When the war came, however, California’s loyal citizens prevailed, thwarting several audacious Confederate plots within the state. Southern loyalists like Gwin were now caught between a rock and a hard place. Some operated clandestinely in an attempt to weaken U.S. control in the state, while others fled for the Confederate South. Gwin was among the exiles. But unlike many of those who returned to the slaveholding states, Gwin did not directly join the Confederate war effort. He had grander ambitions.

***

In October 1861, Gwin enlisted the aid of two of his allies—Joseph Lancaster Brent of Los Angeles and the secessionist lawyer, Calhoun Benham—and boarded the USS Orizaba in San Diego. The ship was sailing for New York, via Panama. But the three rebels never intended to sail for a U.S. harbor. Instead, according to Brent, they planned to “leave the steamer at Panama, make our way to the West Indies, and from there run the blockade into one of the Southern ports.”

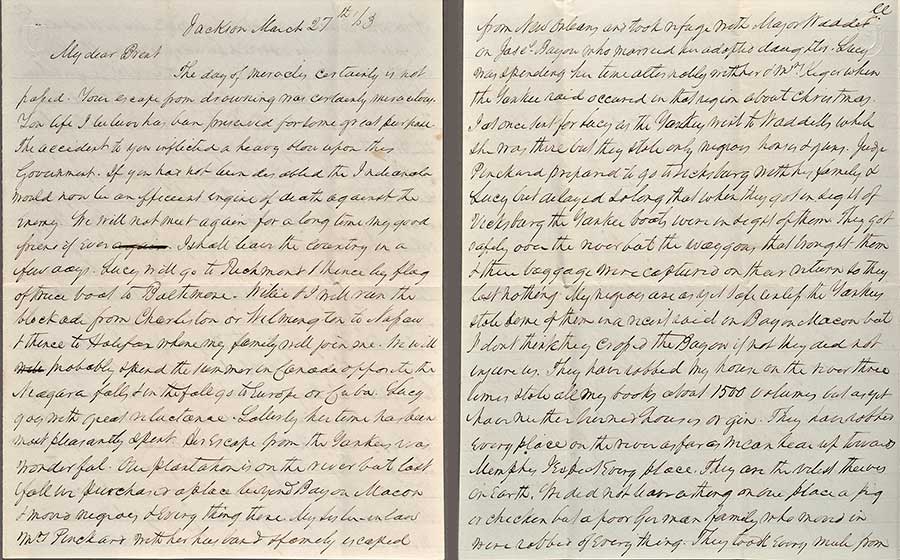

William McKendree Gwin (1805–1885) to Joseph Lancaster Brent (1826–1905), March 27, 1863, first two pages of a four-page letter. In this letter, one of the most important among the Joseph Lancaster Brent papers at The Huntington, Gwin writes to Brent about his plans to leave the United States and later indicates his desire to return to California after a Confederate victory to establish an independent Pacific republic—although he uses guarded terms. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Unfortunately for them, General Edward Vose Sumner, along with 400 U.S. soldiers, had also boarded the USS Orizaba. Sumner, the former commander of the Pacific Department, had been particularly vigilant in his surveillance of California rebels during the opening phase of the war, and he maintained that vigilance aboard the ship. While at sea, he ordered the arrest of Gwin, Benham, and Brent, “all leading, active, and influential men of the party in rebellion against the government.” The order for their arrest, along with many of the documents that detail Gwin’s long, strange trip, can be found in The Huntington’s Brent papers, a unique and seldom-used resource for Civil War scholars.

In protesting their arrest, the three men nearly sparked an international conflict. When the USS Orizaba pulled into port at Panama City, several American southerners there—including the former minister to Panama, who owed his appointment to Gwin—caught wind of the ex-senator’s arrest. They appealed to the governor, who in turn dispatched a company of soldiers to the landing wharf to protest the “violation of the sovereignty of Panama.” Sumner threatened to bombard the city if his orders were resisted and sent the three prisoners ashore, guarded by a flotilla of small boats and 400 soldiers, while a man-of-war pulled into the port and turned its broadside on the city. According to Brent, their arrest was carried out with “a ‘pomp and circumstance of war’ such as [Francisco] Pizarro himself never possessed on the Isthmus when at the height of his power.”

Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889), Napoleon III, oil on red painted hardwood panel, ca. 1865, 12.5 x 16.1 in. (32 x 41 cm). Acquired by William T. Walters, 1887–1893. Courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland.

Thus secured, the prisoners were sent off to New York under parole and later imprisoned at Fort Lafayette. President Lincoln, after vigorous lobbying from a friend (who also happened to be Benham’s brother-in-law), reluctantly agreed to free the prisoners in late 1861. “I never want to hear their names mentioned again,” Lincoln sighed as he ordered their release. He was not to be so lucky. Brent returned to his home state of Louisiana and rose to the rank of Brigadier General within the Confederate cavalry, while Gwin would eventually menace the Union from abroad.

Gwin first went to Mississippi, where he tended to his affairs and his plantation for the next few years, while his son served a brief stint in the Confederate cavalry. Musing on his next steps, he wrote to Brent in March 1863. America was no place for him, he concluded, with U.S. troops closing in on every side. “I want to get away from war,” he wrote. Ultimately, Gwin hoped to return to a California free from U.S. control. With a Confederate victory, he hoped to “put down the Yankees” in his former state and live out his days as a citizen of a newly proclaimed republic. Although sketchy in their details, here were plans for a separate empire on the Pacific: first, southern independence, then the termination of U.S. rule in California.

***

But California had to wait; in the meantime, France beckoned. After Union forces sacked his Mississippi plantation in July 1863, Gwin boarded the side-wheeler R.E. Lee, ran the federal blockade, and sailed for Paris. He joined a large community of southern expatriates, many endeavoring to enlist French aid in the Confederate cause. Although never pledging official support for the slaveholders’ rebellion, the French emperor Napoleon III proved receptive to these overtures—more so than other European heads of state—turning a blind eye to the money and munitions that French sources were sending to the Confederate South.

Jean-Adolphe Beaucé (1818–1875), Le Général Bazaine attaque le fort de San-Xavier lors du siège de Puebla, 29 mars 1863 (General Bazaine attacks the fort of San Xavier during the siege of Puebla, 29 March 1863), 1867, oil on canvas, 84.6 x 147.6 in (215 x 375 cm). © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) Gérard Blot. This painting depicts the siege of Puebla during the French invasion of Mexico.

Thus Gwin had reason for optimism when he won an audience with Napoleon to outline his plan for a new mining colony in Sonora and Chihuahua, Mexico. France had invaded Mexico in the spring of 1862, on the pretext of securing repayment of past debts, and installed the Austrian archduke Maximilian I on the throne of the newly created Mexican Empire. Gwin proposed to unearth the hidden wealth of this empire by attracting American immigrants to the mineral regions of northern Mexico, and to provide a buffer against the United States, which was hostile to Napoleon’s puppet government. All he asked in return was a military detachment of some 1,000 to defend his interlopers against the Indigenous people of the region, who had long claimed that land. Enchanted by Gwin’s assurances of mineral wealth, Napoleon and his cabinet endorsed the plan by the spring of 1864 and dispatched Gwin to Mexico City to prepare the way for the new colony.

Although the former senator pitched his colony as an opportunity for France’s imperial prospects, Gwin had a different empire in mind when he set out for Mexico in the summer of 1864. As he recalled in his memoirs, the Sonora colony was to be a key component in a vast Pacific republic. Had the Confederacy won its independence, “it was believed by many that the country would have still been divided by the separation of California from the Union and the establishment of an independent government on the Pacific coast,” he wrote. “In that event, northern districts of Mexico would have formed an important addition to the Western Republic.” With an army of emigrants, most of them Southern-born, Gwin could exert his political will over a powerful and resource-rich Pacific empire, entirely free from U.S. control.

Édouard Manet (1832–1883), The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, 1868–69, oil on canvas, 99.2 x 120 in (252 x 305 cm). Courtesy of Kunsthalle Mannheim.

Only in hindsight does such a geopolitical reordering appear fanciful or far-fetched. As historian Rachel St. John has argued, Gwin’s visions for Pacific independence were “entirely possible” and consistent with decades of American imperialism. Expansionists like Gwin—men with “grand ambitions and flexible loyalties”—saw “their nation’s boundaries not as a fait accompli but as a work in progress.”

Gwin was just the latest in a long line of Americans, including Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Hart Benton, Daniel Webster, James K. Polk, and Alexander Stephens, who openly mused on the possibility of a Pacific empire. As much as he craved a Pacific outlet for the United States, Jefferson saw little reason to believe that his nation’s dominion would span the entire continent. More likely, he conceded, Anglo-American settlers would establish coexisting confederacies, “governed in similar forms and by similar laws,” across the breadth of North America. Gwin sought to make that possibility a reality.

William McKendree Gwin (1805–1885) to Joseph Lancaster Brent (1826–1905), June 13, 1866, fifth and sixth pages of a six-page letter. Gwin reports on his release from prison at Fort Jackson to Brent and exults in the fact that Gwin never took a loyalty oath to the United States: “Thank God I have never taken an oath [of allegiance] . . .” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In fleeing one war in the United States, Gwin nearly created another in Mexico. When U.S. officials caught wind of his movements in Sonora, they prepared for a border-crossing conflict. Ulysses S. Grant was particularly worried about Gwin, “a rebel of the most virulent order.” So too was General Irwin McDowell, commander of the Pacific Department. Two of Gwin’s agents were then operating in San Francisco to recruit would-be colonists and thereby “plant upon our frontiers a people hostile to our institutions, our influence, and our progress,” McDowell wrote. In response, the general drove the two immigration agents from San Francisco, then instituted a policy requiring passports for all Mexican-bound travelers. Meanwhile, he dispatched a brigadier general to Arizona to monitor Gwin’s movements, and organized a force of several hundred men to “provide for any contingency.”

Gwin wasn’t officially commissioned by the Confederate government, but Confederates cheered his progress. “[I am] highly valued,” Gwin wrote, “because I am with the South in this contest.” John Slidell—the Confederate minister to France, who had been privy to Gwin’s dealings in Paris—held high hopes for the Sonora mission. “His object is to colonize Sonora with sons of southern birth… residing in California,” Slidell wrote to Confederate secretary of state Judah P. Benjamin. “If carried out its consequences will be most beneficial.” Geographic factors alone, as Slidell probably recognized, would have lent the Sonora colony a southern character. In close proximity to rebel Arizona and Confederate-sympathizing Southern California, the Sonora colony would be a magnet for nearby disunionists. As the Confederacy’s armies crumbled in the East, Gwin’s colony could have opened a rebel escape valve in the West.

Mathew Brady (1822–1896), William M. Gwin, between ca. 1860 and ca. 1865. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Yet for all the Unionist fears and Confederate expectations that he stirred, Gwin’s Mexican career was short-lived. A medley of factors beyond his control—interpersonal struggles within the court of the French-controlled Mexican emperor Maximilian, the tenacious resistance of President Benito Juárez’s Liberal armies, administrative missteps—doomed his best laid plans. Gwin began recruiting in California, but without French military, mining operations could not safely commence. Gwin—ridiculed by the Unionist press as “El Duque de Guino” (“Gwin, the Duke”)—continued pressing his case until early in the summer of 1865, several months after the Confederacy’s collapse. By July, however, he finally abandoned his plans and rode from Mexico City under an armed escort.

Maximilian eventually faced a firing squad of Juárez’s victorious soldiers; Gwin was fortunate to escape with his life—a fact he attributed to the poor marksmanship of the Mexican Liberals. But he had merely leaped from the frying pan and into the fire. Back in the United States, and with Confederate rebellion quashed, the former senator was arrested and transported under guard to Fort Jackson, Louisiana, in October 1865.

Kevin Waite, West of Slavery: The Southern Dream of a Transcontinental Empire (University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

He languished there for nearly eight months, until April 1866. Aside from Jefferson Davis, no Confederate high official served such a long prison term after the war. And for good reason. Gwin’s border-crossing adventure was among the boldest separatist schemes of the war. Other California rebels had raised funds and arms for the Confederate war effort; some even fled the state to join the rebel army. But only Gwin had dared to conspire with foreign dignitaries and to launch a colony intended as the southern extension of an independent Pacific republic. As the United States attempted to reassert sovereignty over the former Confederacy, Gwin’s actions highlighted the globetrotting nature of the recent rebellion, when the slaveholding South reached into the courts of emperors.

You can watch Kevin Waite discuss his book, West of Slavery: The Southern Dream of a Transcontinental Empire, with Alice Baumgartner, assistant professor of history at USC, and Andrés Reséndez, professor of history at University of California, Davis, here. His book is available from the Huntington Store here.

Kevin Waite is assistant professor of history at Durham University in England.