What’s Hidden in the Gutenberg Bible?

Posted on Tue., March 11, 2025 by

Christ on the Mount of Olives. Metal-cut relief print, hand-colored. Germany, ca. 1455–1465.

| The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.It’s not every day that a curator gets a chance to reunite a lost print with its centuries-old companion. But for Stephen Tabor, The Huntington’s curator of rare books, that opportunity arrived with an unexpected email from a British colleague last spring.

An exceedingly rare 15th-century print of Christ on the eve of his crucifixion—once affixed inside The Huntington’s copy of the Gutenberg Bible—was for sale in London. Would he be interested?

Tabor thought he’d died and gone to heaven.

Several months of research, export-license delays, and fundraising ensued. Finally, in September, the hand-colored relief print, roughly the size of a sheet of typing paper, arrived by courier, sealed in a “wooden casket befitting a lost ark,” as Tabor put it.

The print is one of three originally pasted inside the Bible’s covers, likely by an early owner in the 15th century. Two identical Christ on the Mount of Olives prints—the one now at The Huntington and the other at the University of Manchester—were accompanied by Crucifixion, twice as large but sadly damaged, now housed in the British Museum. When the Bible was auctioned in 1825, these prints were removed and sold individually, destined to travel separately for the next two centuries.

Reunited with The Huntington’s Gutenberg Bible, the print is on view in the Library Exhibition Hall from March 12 through May 26, 2025. This rare display offers a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to witness two cultural treasures side by side. (For more details on the print, read the news release about its acquisition.) The reunion has also led to the discovery of scholarly Easter eggs hidden in the book’s margins.

A Masterpiece among Masterpieces

Tabor first learned of the three prints’ existence seven years ago when Princeton University’s Eric White published a definitive study of all known Gutenberg Bibles. White, probably the world’s foremost Gutenberg expert, describes The Huntington’s copy—a richly illustrated, 16-inch-tall, 50-pound, two-volume work—as “astoundingly beautiful.”

Of the fewer than 200 original copies printed by Johann Gutenberg (ca. 1397–1468), only 48 survive today in at least one volume. The Huntington’s copy is among just 12 printed on vellum (calfskin) and one of 11 in their original binding. Even more remarkably, it is one of three that share both qualities—and the only one of these that includes both volumes and is illuminated (embellished with paintings and gold flourishes).

“The Huntington illumination is an outlier,” White said during a 2021 lecture at The Huntington. “The forms are rounder and more graceful; the colors are deeper and more varied.”

Detail from the Gutenberg Bible, ca. 1455–1500.

| The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.White’s sentiment echoes a letter from 1813, in which Alexander Horn, the Bible’s then-owner, wrote to the second Earl of Spencer (Princess Diana’s ancestor): “The illuminations, or gildings and paintings, are uncommonly beautiful, and I can say without exaggeration that there is not a more glorious book in the world.”

The Gutenberg Revolution

Printed in Mainz, Germany, in the 1450s, Gutenberg’s Bible is often mistakenly referred to as the first printed book. In fact, several centuries earlier, Chinese printers used carved wood blocks, ink, and paper to reproduce Buddhist texts. Likewise, movable metal type can be traced to the printing of the Jikji, another Buddhist work, in late 14th-century Korea.

The Gutenberg Bible was not even the first book printed on Gutenberg’s own press. That distinction belongs to various “lesser” texts, including calendars, schoolbooks, religious indulgences, and a pamphlet of anti-Ottoman propaganda.

However, the Gutenberg Bible was the first major book printed with movable type in the West, revolutionizing the distribution of knowledge. Its publication established typography as the first commercially viable method of producing hundreds of virtually identical copies, lowering the cost of books throughout Europe and making literature and the study of history and science more widely accessible than ever before.

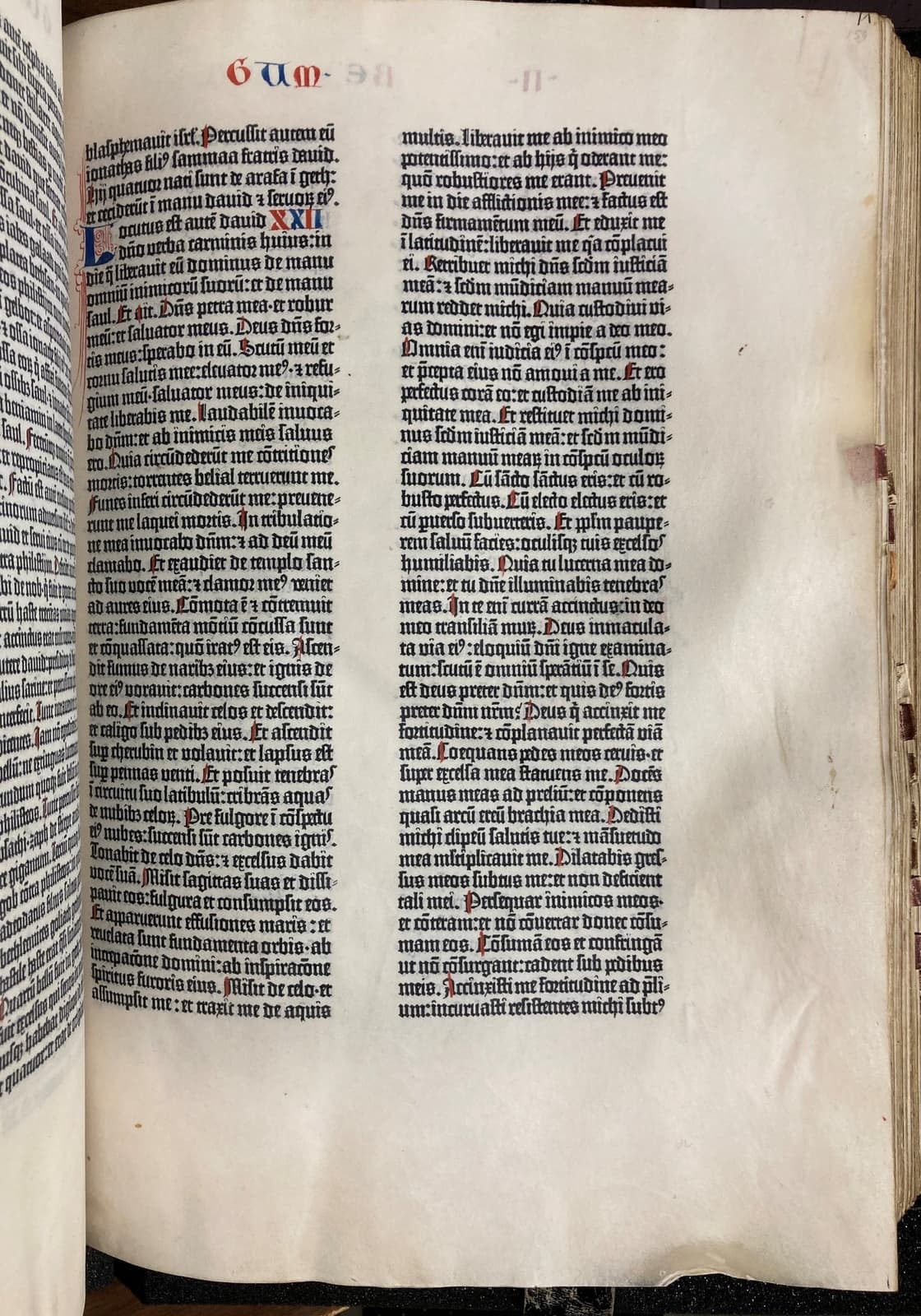

A spread from the Gutenberg Bible, ca. 1455–1500.

| The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.Signs of Life in the Margins

Beyond the intricate artistry of its illuminations and Gothic-lettered Latin scripture, and in addition to its historical significance, The Huntington’s Gutenberg Bible preserves the untold stories of those who printed, owned, and cared for it across nearly six centuries. While movable type allowed for uniform printing, this book is rife with human touches—workshop inconsistencies, fingerprints, signs of printer fatigue, and other simple errors that have become invaluable evidence to scholars.

Imagine making a small workplace mistake, only to have it preserved, studied, and discussed for centuries.

Richard N. Schwab, writing in a 1988 Huntington Library Quarterly (HLQ) article, described The Huntington’s copy as “one of the tallest and best preserved,” noting that its pristine margins made it an “unequalled arena” for studying printing techniques. Among the most telling clues? Tiny pinholes left from mounting the vellum leaves for printing. By observing their patterns and the anomalies in the holes relative to the text columns, scholars have been able to deduce some of the earliest practices in Gutenberg’s workshop and the structure of the printing apparatus itself. (To learn more than you ever realized could be said about pinholes, read the HLQ article.)

Reading with Fresh Eyes

The acquisition of the Mount of Olives print inspired Tabor to meticulously examine each of the Bible’s 1,280 pages—something neither he nor his predecessor had done before. During his winter holiday, he cataloged a wealth of findings, especially “things we’re not supposed to see.” These included additional pinholes that map out the book’s printing process; foliation and other markings in pen and pencil; and inky fingerprints caused by less-than-careful handling of the sheets in the workshop.

Left: Stephen Tabor, The Huntington’s curator of rare books, with the Gutenberg Bible, 2025. Right: A stitched hole in the vellum (calfskin) from a page in the Gutenberg Bible, ca. 1455.

| The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.Tabor also discovered manufacturing defects in the vellum, including stitched or patched rips—evidence of the challenges in preparing animal skins for large books. Processing the skin can cause holes to develop, much like when stretching pizza dough. “The bigger you want your book to be, the more defects you have to accept,” he said, “because you can’t cut your sheets to avoid them if you’re laying them out right to the edge of the skin.” These details give the vellum copies of the Bible an added dimension: wound-like imperfections that make it uniquely human (or, perhaps more accurately, corporeal—each of The Huntington’s two volumes was made from the skins of more than 80 calves).

The image below is of an ordinary-looking page in 2 Kings from The Huntington’s Gutenberg Bible. A close inspection of the page reveals five examples of physical evidence that convey something about the history or manufacture of the book. Each piece of evidence takes us further back in time.

For more information from curator Steve Tabor about each piece of evidence, click the image’s hotspots.

1. Mead Mark and Quires

Late 1920s: There is the faintest penciled “r” here, and it was made by Herman Mead, Henry Huntington’s cataloguer of early printing. It dates from the late 1920s. The “r” means this is the start of the seventeenth gathering in the volume.

A gathering or quire is the basic unit of a bound book, either manuscript or printed. It’s a group of sheets that are folded together and sewn through the fold, a sturdy structure that makes it difficult for individual leaves to fall out. In the Gutenberg Bible most of the gatherings contain five sheets.

To keep the gatherings in the right order, they’re assigned letters or numbers, which printers later in the century started printing in their books. In the early period they didn’t do this, so Herman Mead here is looking at the folding patterns and previous descriptions, finding where the quire breaks are, and marking them to keep his bearings while he’s confirming that everything is in order—something he did with all The Huntington’s early unsigned books.

2. Pencil Foliation

Early 19th century: This next-earlier bit of evidence, a lightly penciled “159,” is the leaf number. Remarkably, Gutenberg failed to include any foliation or pagination, so someone later had to do this by hand. From the style of handwriting, we can tell the numbers were added in the early 19th century, when our copy first entered the English market. Combined with Herman Mead’s signature marks, they help to tell us where in the book we are.

3. Pen Quire Number

Mid-15th century: This is the number 17. We learned earlier that quire “r” was the 17th gathering in the book, so the person who wrote this was numbering the quires. The handwriting style is very old; looking at other examples in the book, it’s likely contemporary with Gutenberg. The person marking up copies, the illuminator, and the binder all needed orientation, so this was a necessary job for somebody in the printing shop.

4. Pen Signature Number

Mid-15th century: This little mark is a very deliberate number 1. The subsequent leaves continue the numbering up to five.

These are manuscript signature marks—they’re numbering the sheets as they come off the press to keep them in order when they gather the signatures. In later centuries, they were printed along with the text, but Gutenberg’s workers were doing this by hand. Marks like this are normally cut away by the binder while trimming the leaves to make uniform edges, so it was pleasantly surprising to find a good number of them in our Bible.

5. Point Hole

1450s: This little hole at the bottom was made by a dagger-shaped pin that helped to hold the vellum sheet to a backing while it was being pressed onto the type. There might be up to ten of these on each leaf of the book, though they are easily missed. Many of them have been trimmed off.

A Journey through Time

The Bible’s margins also reveal clues about its provenance. Eric White notes that both volumes of The Huntington’s copy bear signatures of ownership by Otto II, Freiherr von Nostitz (1608–1664), whose extensive library at Schloss Jauer (near modern-day Wrocław, Poland) also held Nicolaus Copernicus’ unique autograph manuscript of De Revolutionibus, which features the same mark of ownership on its front flyleaf. While the Bible’s original owner is unknown, it may well have been an earlier Nostitz.

Until at least the late 18th century, the book remained in the Nostitz family library, which was moved to Prague in 1669. It reemerged in 1813 in the possession of London bookseller George Nicol. In May of that year, as French troops occupied Prague, Alexander Horn—a former Scottish monk who became a European spy and book scout(!)—bought the Bible from the Nostitz collection and dispatched it to Nicol. Hoping to increase its value, Nicol had facsimiles of two missing leaves inserted into the volumes, but he failed to find a buyer. When the Bible was auctioned in 1825, its three 15th-century prints were removed and sold separately.

The Bible changed hands several more times before landing in the collection of American businessman Robert Hoe III. In 1911, dealer George D. Smith acquired it on behalf of Henry E. Huntington, who made international headlines when he purchased the Bible for $55,000 (equivalent to nearly $2 million today)—more than twice the previous highest sum paid for a printed book at auction. This purchase happened early in Huntington’s book collecting career and helped establish him as “one of the most determined bibliophiles of the age,” according to a New York Times article announcing the sale.

Left: Portrait of Henry E. Huntington, ca. 1917. Photo by Arnold Genthe (1869–1942). Right: Cover of the Gutenberg Bible, ca. 1455–1500.

| The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.Restoring a 500-Year-Old “Suit of Armor”

In 1817, English clergyman and author Thomas Frognall Dibdin described the Bible’s binding as nearly indestructible:

The volumes are absolutely cased in mail … [with] knobs and projections, in brass, of a durability, and bullet-defying power, which may vie with the coat of a rhinoceros.

Even so, by 1977 time had taken its toll. The Huntington’s conservation specialists replaced the Bible’s worn leather spine and underlying cords with new calfskin stained to match, rehinging the heavy oak covers and restoring their brass clasps. Earl Schneider, The Huntington’s specialist in binding at the time, oversaw the restoration work and personally rebound the second volume. The project was the crowning achievement of his 26-year career. His goal? That his work, like the original binder’s, would last for centuries.

A Legacy of Connection

The Gutenberg Bible has passed through many hands for nearly six centuries, each one leaving a mark on its story. The Bible isn’t just a priceless artifact; it’s a testament to the people who created, preserved, and studied it.

“The fact that we’re talking about a Gutenberg Bible today,” White said in his Huntington lecture, “is not because we care about that Latin Bible and where it was in 1455. It’s because we care about the history of people.”

And now, thanks to a chance email and a prodigal print, that history has gained yet another remarkable chapter.

Andrew Kersey is the senior writer in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.