Posted on Mon., Oct. 3, 2011 by

Ask Frances Dolan if she believes in witches and she'll likely tell you you're asking the wrong question. "I'm more interested in how people come to believe what they believe."

In her lecture on Tuesday night, Oct. 4, this year's Fletcher Jones Foundation Distinguished Fellow will explain how 17th-century witchcraft trials offer up lessons in historical evidence and the power of stories.

"You'd be surprised how many acquittals there were in these trials," says Dolan, explaining how people in the 1600s might have been more superstitious than we are today, but they were still discriminating. How exactly did they separate credible and incredible testimonies? Her lecture is titled "True Relations and Ridiculous Fictions: Evaluating Stories of Witchcraft in 17th-Century England."

Dolan, a professor of English from UC Davis, says readers in the 17th-century were bombarded with information from a booming print culture. They read books, pamphlets, newspapers, whatever they could get their hands on. And one kind of literature that proliferated was in a category called "True Relations."

"A 'True Relation' at one level is just another way of saying 'an account' or 'a narrative,'" she explains. "So in the 17th century you'll find texts called news or a report or a narrative, but more often than not, the title is a 'True Relation' of this or that." In one way, the tagline indicated that an author was making a bold proclamation that no matter what someone else had written on the subject, this new book was the last word.

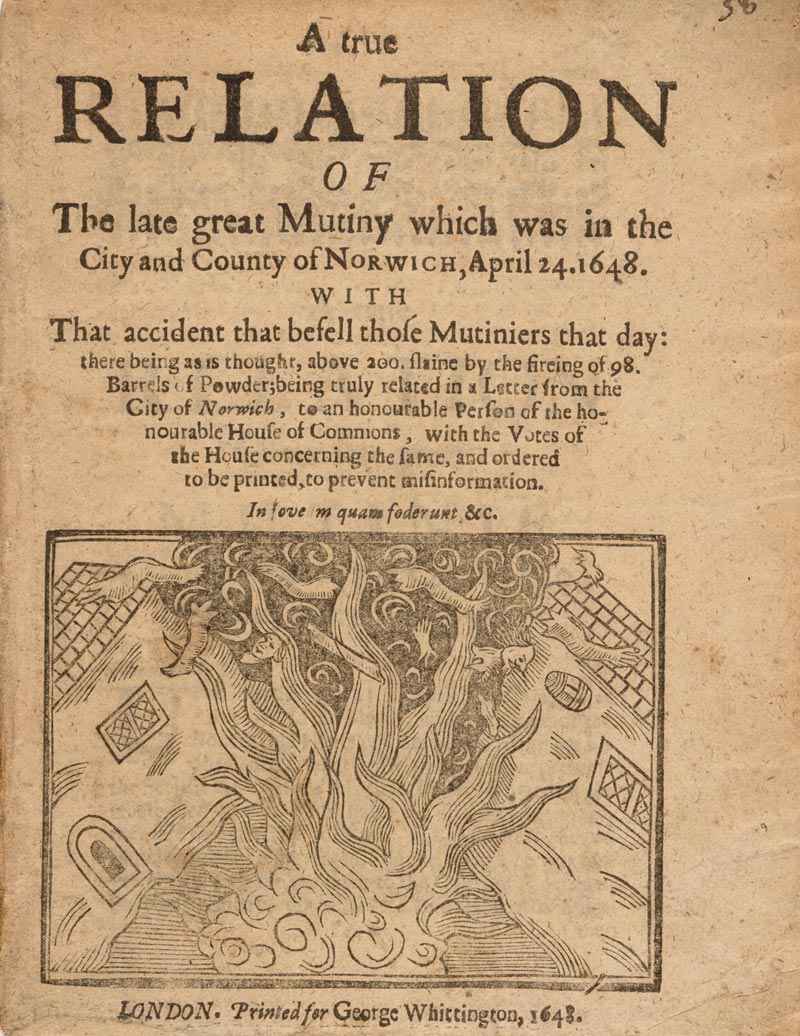

Since beginning her fellowship in September, Dolan has been reading through every "True Relation" she can find in the Huntington collection: A True Relation of the Late Great Mutiny which was in the City and County of Norwich, April 24, 1648; A True Relation of a Barbarous and Bloody Murder; A True Relation of a Great Number of People Frozen to Death Near Salisbury.

War, witchcraft, murder, politics, religion, global exploration—stories about each were subject to debate, and each new author who came along positioned his or her version as the truth. Dolan's research on True Relations extends to the conflicting accounts of big events such as the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 and the Great London Fire of 1666. Plays and court depositions also factor into her assessment of the evidence that helps her make sense of the past.

In the case of witchcraft, persuasive stories had life and death consequences. "I want to read these as if they really matter," Dolan says. "Just like a Londoner in the 1600s trying to make sense of witchcraft."

Dolan's lecture takes place on Tuesday, Oct. 4, at 7:30 p.m. in Friends' Hall. It is free and open to the public.

Matt Stevens is editor of Huntington Frontiers magazine.