Posted on Tue., Oct. 16, 2012 by

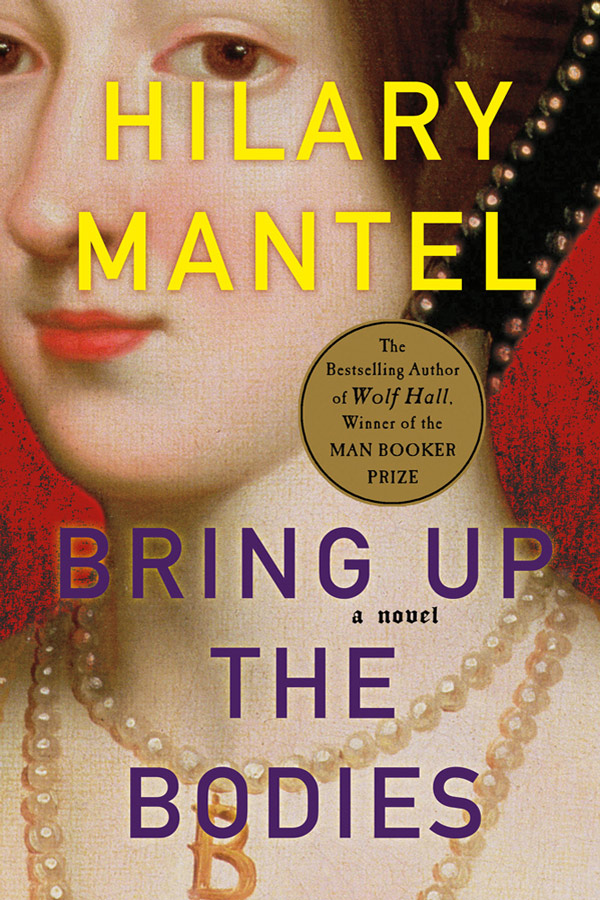

The BBC reported earlier today that Hilary Mantel has won the Man Booker Prize for her novel Bring Up the Bodies. The book is a sequel to Wolf Hall, which won the Man Booker Prize in 2009. Mantel’s papers are housed at The Huntington.

Mantel is the first British author—and the first woman—to win one of the most coveted literary prizes twice. Peter Carey (of Australia) and J. M. Coetzee (born in South Africa, now an Australian citizen) have also won it twice. The website of the Man Booker Prize says that Mantel is “also the first to win with a sequel and the first to win with such a brief interlude between books.”

Mantel’s two prize-winning books tell the story of Thomas Cromwell (1485–1540), the chief minister to Henry VIII who played critical roles in the king’s divorce of Catherine of Aragon (the subject of Wolf Hall) and his ensuing marriage to Ann Boleyn. Cromwell later plays a vital role in Boleyn’s imprisonment and execution in 1536 (Bring Up the Bodies). A third book will take the reader up to Cromwell’s own demise, in 1540.

Perhaps most surprising in Mantel’s feat is that she has won two of the last four Man Booker Prizes for historical fiction, a genre that is seldom in favor among critics or judges on award committees.

A timely profile in this week’s New Yorker by Larissa MacFarquhar discusses the author’s first published book, a historical novel about the French Revolution, and how Mantel grappled with rejections by going on to master thin, spare novels set in the present.

The title of MacFarquhar’s article, “The Dead Are Real,” alludes to the many ways Mantel couldn’t let go of historical figures in her novels, not to mention the many ways she encountered ghosts in her day-to-day life (she calls her memoir Giving Up the Ghost).

But the New Yorker headline ultimately pays tribute to how Mantel makes history come alive in her fiction in ways that few other writers—novelists or historians—have managed. Her approach to writing is not one of invention.

Mantel says, as quoted by MacFarquhar: “I cannot describe to you what revulsion it inspires in me when people play around with the facts. If I were to distort something just to make it more convenient or dramatic, I would feel I’d failed as a writer. If you understand what you’re talking about, you should be drawing the drama out of real life, not putting it there, like icing on a cake.”

Mary Robertson, The Huntington’s William A. Moffett Curator of English Historical Manuscripts, knows Mantel well and speaks highly of her commitment to accuracy. After Mantel won her 2009 award, Robertson spoke of the novelist’s unique approach: “In some ways, it takes a greater skill to work with everything that is known—and from that add your imagination to craft a convincing story—than it does just to make it up.”

Matt Stevens is editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine.