Posted on Tue., March 5, 2013

Steve Hindle, the W. M. Keck Foundation Director of Research at The Huntington, will present a lecture at 7:30 p.m. on Wednesday evening, March 6, in Friends’ Hall. His subject: The economic history of 18th-century rural England. Here he explains how he arrived at a visual representation of that story.

The Montagu Family at Sandleford Priory (Berkshire), by Edward Haytley, 1744. Private collection, image courtesy of Lowell Libson Ltd.

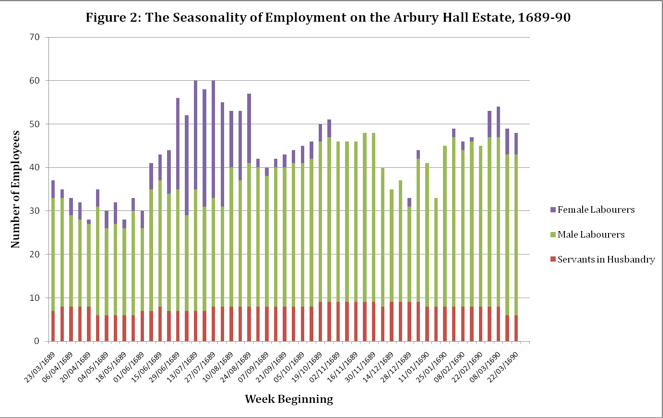

As an economic historian of labor markets in 17th- and 18th-century England, I have spent many painstaking hours calculating labor participation rates in the agricultural workforce on the Newdigate estate at Arbury (Warwickshire). This requires the linkage of personal names between wages books and other census-type material to identify the age and gender of those who worked in the fields, at what time of year they were employed, and the terms on which they were paid. I am very proud of the resulting graph (see below). I like it because it demonstrates a spike during an eight-week period in the months of June and July of the numbers of women employed, in contrast to the remainder of the year when their presence in the fields of the estate was sporadic to say the least. The graph offers statistical proof of the significance of female labor inputs during the time of the hay harvest.

The more I talked about the graph in lectures and seminar papers, the more frustrated I became by the lack of enthusiasm among my audience. Eyes glazed over; postures slumped. Convinced that I needed a more visually inspiring way of making the same point, I turned to a little-known 18th-century landscape painting, and gradually began to show it as part of my presentation (see above).

What appealed to me, of course, was not the presence of the gentry family at leisure on the terrace in the foreground, but the visibility in the distance of eight agricultural laborers raking and stacking hay. The fact that six of the eight were female helped me make the point about the importance of female employment during the hay harvest.

But the more I showed the picture as light relief from hard-hat economic history, the more questions I received about the painting itself and the more curious I became about it. Who were the gentry family in the foreground? Why does the landlord have a telescope on his desk which appears to be directed at the labor force? Why are so few of the laborers actually working? In fact, only one of the eight immediately visible figures can be said to be engaging in unremitting toil. The others are bantering, drinking (or restraining their fellow from drinking) or defiantly staring at their patrician landlords, rake raised away from the grass and hand coquettishly on hip (see Detail 1). Close study revealed the presence of a ninth figure, almost certainly a single male (though he may just possibly be accompanied by a partner!) lying recumbent and quite possibly asleep under the hedgerow at the very center of the painting (see Detail 2).

So it became obvious that the painting required investigation in its own right. The research potential is, frustratingly, both very limited and extremely strong at the same time. On the one hand, nobody knows where the painting is. It was sold at Sotheby’s in 1979 into private hands somewhere in the United States, and the agent in the sale signed a confidentiality agreement not to reveal the identity or whereabouts of the purchaser. On the other hand, the family in the foreground are Edward and Elizabeth Montagu and Elizabeth’s sister Sarah Scott, painted by Edward Haytley on their estate at Sandleford priory in Berkshire some 30 miles west of London in 1744. This is very good news, since the Huntington Library collections include some 7,000 letters from Elizabeth Montagu to a network of correspondents all over Britain from the 1740s to the 1780s. For the last few months, I have been gleaning through these letters to analyze the attitudes of the Montagu family toward the landscape which surrounded their estate and the labor which was conducted upon it. The letters are extraordinarily revealing of Elizabeth Montagu’s paternalistic desire to act charitably toward her poor neighbors and employees, but they also reveal her frustration that her husband was so reluctant to improve the estate and transform surroundings which she thought dull and uninspiring into a manicured pleasure garden. Indeed, it was only when Edward Montagu died in 1775 that Elizabeth had free rein to remodel the estate and to employ Capability Brown as the landscape designer for the emparkment. The world depicted with such topographical accuracy in Haytleys’ painting was destroyed forever.

But by now, as I am sure you can tell, I had grown far more interested in the Monatgus at Sandleford than I had been in the Newdigates at Arbury: one research problem had, as it so often does, raised a whole series of others. The result is a paper entitled “Representing Rural Society: Labor, Leisure and the Landscape in an Eighteenth-Century Conversation Piece,” which is currently under consideration for publication in a major journal. This academic diversion has been both challenging and stimulating forcing me out of my comfort zone to ask art historical questions which an economic historian is ill equipped to answer. But I have had great fun and, more importantly, learned a lot.

Oh, and one last thing: if you know anything about the whereabouts of this painting, do let me know.

The painting graces the cover of a new book edited by Hindle, Alexandra Shepard, and John Walter: Remaking English Society: Social Relations and Social Change in Early Modern England. It will be published in May by Boydell Press as part of its series titled Studies in Early Modern Cultural, Political and Social History. Find out more at the publisher’s website.

Steve Hindle is the W. M. Keck Foundation Director of Research.