Posted on Thu., July 18, 2013 by

The beds of The Huntington’s Desert Garden are rich with displays of cacti and succulents from around the world. Photo by Lisa Blackburn.

With so many plants in the Desert Garden, it is not surprising that over time some of them begin to blend into the busy landscape. This has created a challenge for the many generations of Huntington staff who have been involved in the Desert Garden Survey, a project that was first started in 1932 and continues to this day. In the process, we’ve learned that tracking down the names and numbers of cacti and succulents can sometimes take the form of a compelling botanical detective story.

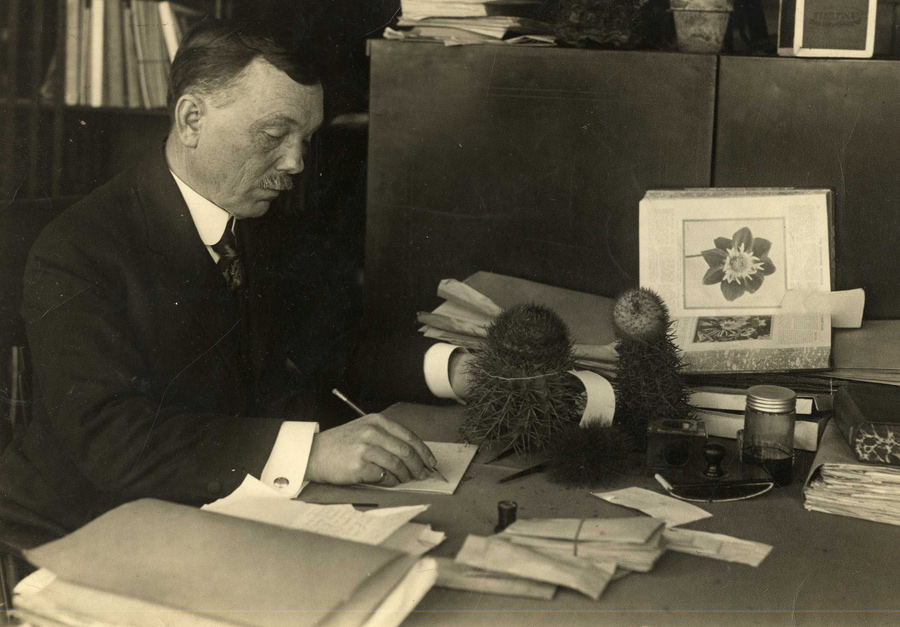

J. N. Rose at his desk, date unknown. Courtesy of the Robert T. Ramsay Jr. Archival Center, Wabash College, Crawfordsville, Ind.

In the early part of the 20th century, many of the great cactus and succulent researchers of the day would send plant material to William Hertrich, the legendary superintendent of Henry E. Huntington’s grounds from 1905 to 1948. Foremost among these cactus experts was Dr. Joseph Nelson Rose, an American botanist at the U.S. National Herbarium.

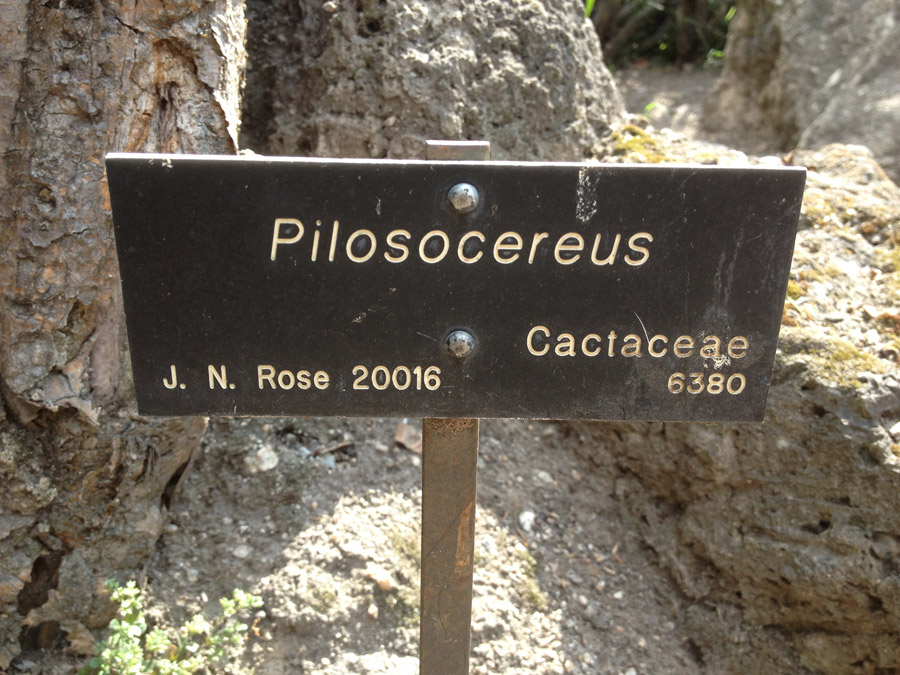

Labels from the Desert Garden credit J. N. Rose as the source of many specimens. Photo by Sean Lahmeyer.

Perhaps best known for coauthoring the definitive treatment The Cactaceae(cactus family) in 1920 with Nathaniel Lord Britton, Rose helped name and describe 972 species of cacti throughout his illustrious career. With Rose’s fieldwork taking him throughout the United States, Mexico, and countries in South America—at a time when researchers were discovering and describing many new cacti—his research collection was a gold mine. After his death in 1928, the U.S. Department of Agriculture distributed his collection, most notably through the U.S. Acclimatization Garden, Torrey Pine Station, in La Jolla, Calif., which subsequently sent more than 700 plants to The Huntington from 1932 to 1942. An equal number came to us from the USDA’s Chico Station.

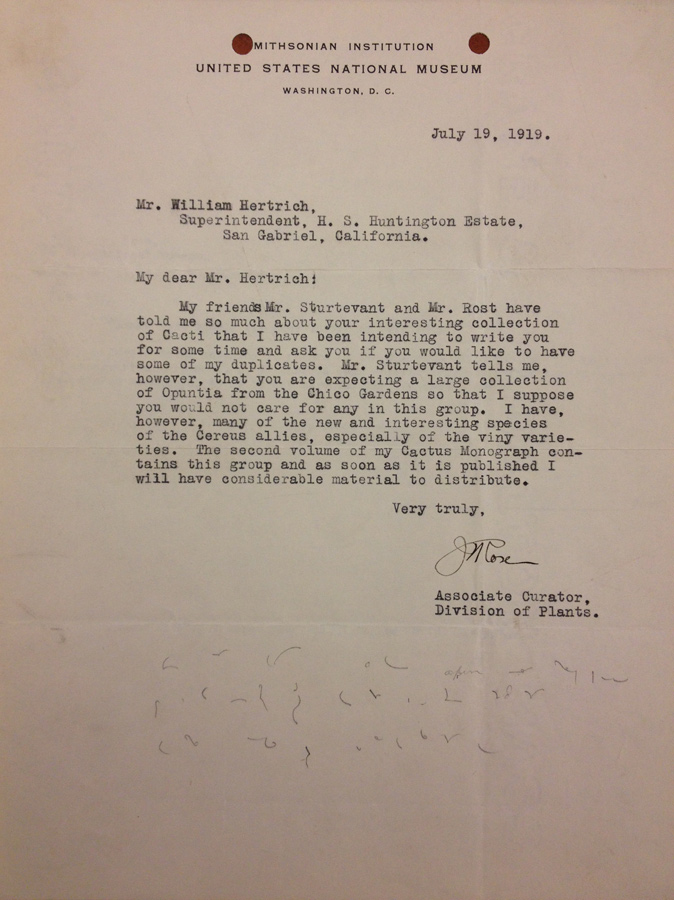

Rose’s paper trail includes correspondence with William Hertrich regarding his collection.

This is where our current survey picks up the story some 70 years later. Even though many of Dr. Rose’s plants are long gone, we determined the remaining plants were worth a closer look. But we were stumped by the numbers on many of Rose’s labels; they didn’t seem to correlate to anything. After months of communicating with our friends at other botanic gardens, we uncovered several Rosetta Stones. First, we learned that our numbers were an old internal numbering system used by the USDA, termed “CPB” numbers, which were issued by the old Office of Crop Physiology and Breeding. Months later, completely by chance, we came across several folders in storage that turned out to be the original receiving notes from Hertrich, with both our CPB numbers and a new set of numbers—Rose’s greenhouse numbers. Jackpot! This exciting discovery prompted us to contact the Smithsonian. We learned that Rose kept detailed greenhouse notes for his entire research collection, and in time we obtained scanned copies. The valuable information gleaned from the notebooks linked directly to Dr. Rose’s plants remaining in our Desert Garden. We’ve now generated an interactive GIS map of the Desert Garden, so take a look for yourself at some of the plants that remain from Dr. Rose.

I would like to acknowledge both Maxx Echt and Katie Chiu for assisting with the GIS map portion of this post.

Sean C. Lahmeyer is the plant conservation specialist at The Huntington.