Posted on Wed., Jan. 28, 2015 by

Thomas Rowlandson’s satirical views of Georgian society are among his strongest work, and The Huntington’s collection focuses primarily on this aspect of his oeuvre. Eleven of his works are on view in “Working Women: Images of Female Labor in the Art of Thomas Rowlandson.”

Today’s pop culture often goes overboard by invading personal privacy in the search for entertainment. Britain’s Georgian era (roughly 1714 to 1830) was a similarly nosy time—gossiping and people watching were especially popular pastimes, as were reading biography and looking at portraiture. Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827), one of Britain’s premier draftsmen, was also an astute social critic who commented on the goings-on of the day through his comic drawings and caricatures.

To get a sense of his style, stop by the Works on Paper room on the second floor of the Huntington Art Gallery. “Working Women: Images of Female Labor in the Art of Thomas Rowlandson” draws from The Huntington’s collection of more than 600 original drawings by the artist. On view are 11 rarely exhibited watercolors, depicting women who were most visible in the public sphere—street vendors, servants, actresses, and prostitutes—with an occasional glance at the foibles of the upper class.

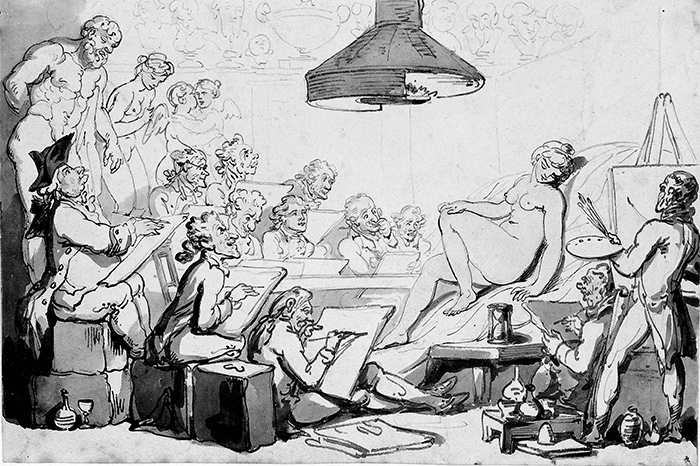

In The Life Class, Rowlandson pokes fun at old men leering at a young, naked model. The one serious artist is also the young and handsome one—could it be Rowlandson? (No date, pen and gray wash, rendered here in black and white.) The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gilbert Davis Collection. On view in “Working Women.”

Rowlandson was incredibly observant in the way he showed people’s everyday pitfalls, especially in his frequent depiction of voyeurs. One of the most common objects of his gaze (and that of his subjects) is a pretty young woman. The artist arranges all action around this central figure. Take The Life Class, in which men gather around a nude woman, ostensibly to use her as a model for their painting. Instead of diligently working, however, Rowlandson shows the men leering at the model, clearly more interested in her nakedness than in getting on with their canvases. Rowlandson dramatizes their overtly lascivious gazes with exaggerated expressions. His jest suggests that these would-be artists will be unsuccessful in bringing their lusty plans to fruition.

Thomas Rowlandson, Rowlandson and his Fair Sitters, no date, pen and watercolor, rendered here in black and white. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Homer Crotty. On view in “Working Women.”

In contrast, the only man not depicted in caricature is a young and handsome one, likely Rowlandson himself, as he stares wistfully at the model. If anyone has a chance to interact with the pretty young woman, Rowlandson seems to be saying, it is he—the equally handsome young man. Yet at this moment, all he can do is create art out of her image. Rowlandson intimates that such looking is a diluted experience of the world, one that he and the men he caricatures engage in as a poor substitute for the real thing.

Is Rowlandson saying that art takes the place of a more profound engagement with the world? Maybe not. Regardless of how much Rowlandson makes fun of the old men, we appreciate his artwork for giving us the opportunity to interact with his cast of characters. By recording what he has observed, Rowlandson gives us a unique (if acerbic) view into Georgian life.

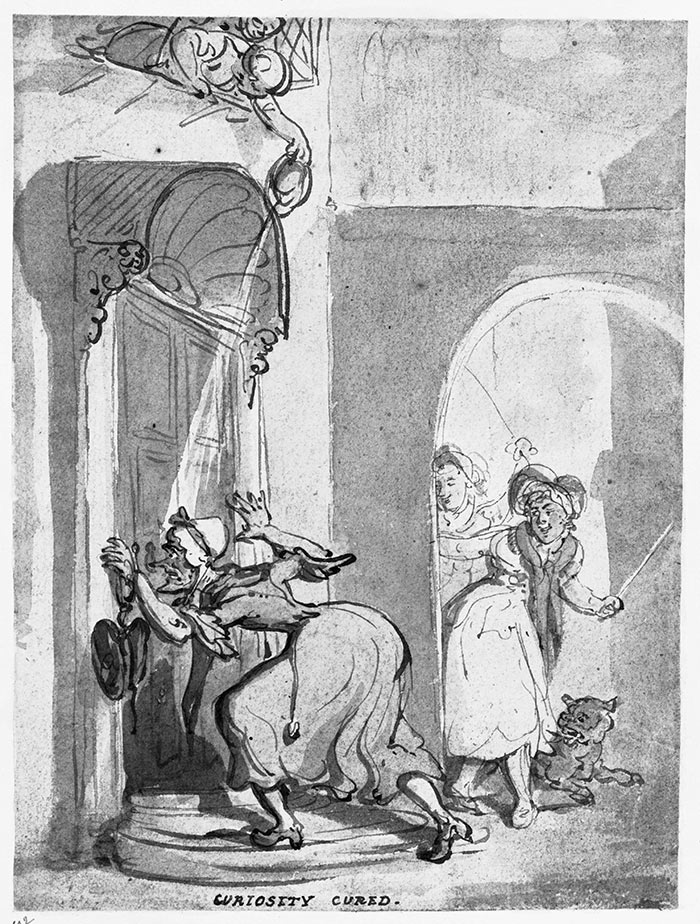

In Curiosity Cured, Rowlandson shows little patience for an old woman’s prurience. His suggested cure: a judicious thwack. (No date, pen and watercolor, rendered here in black and white.) The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“Working Women: Images of Female Labor in the Art of Thomas Rowlandson” will run through April 13, 2015 in the Works on Paper room, on the second floor of the Huntington Art Gallery.

Mairead Horton served as an intern in the art division at The Huntington. She is currently studying art history at Princeton University.