Posted on Wed., Feb. 25, 2015 by

The Huntington’s library collection comprises nearly 9 million manuscripts, books, photographs and other works in such fields as American and British history, literature, art, and the history of science. Because of the sheer volume of materials—with each item having to be analyzed by hand and carefully studied—it’s possible for things to remain hidden for decades before a staff member or researcher comes along and has a thrilling moment of discovery.

Such a moment recently transpired for researcher Stephen Snobelen. What follows is his account of a new finding in the Library that is generating excitement as it signals opportunities for further scholarship.

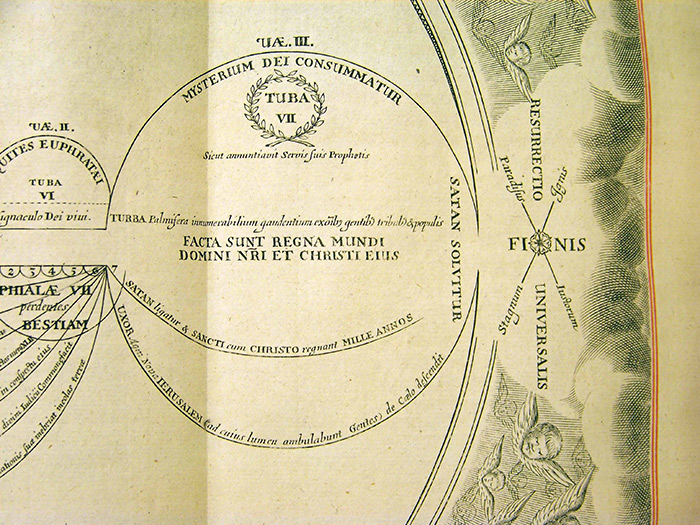

Detail showing the future Millennium from the apocalyptic time chart found in Newton’s copy of Mede’s Works (1672). Mede’s chart likely helped inspire Newton’s own apocalyptic beliefs. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

An Unexpected Revelation

Less than an hour before books were recalled from the Ahmanson Reading Room in the Munger Research Center, I brought to my desk one of The Huntington’s two copies of Joseph Mede’s Works (1672), a 1,000-page book of exceptional erudition on biblical exegesis written in English, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew.

It was the Friday afternoon before the long Martin Luther King Jr. weekend, but I intended to spend a few minutes with this grand volume. Mede, who died in 1638, was a prophetic interpreter and a major inspiration for the famous physicist Sir Isaac Newton, who wrote extensively about biblical prophecy and adopted Mede’s historicist interpretation of the Apocalypse.

The Huntington has several copies of the four editions of Mede’s Works, going back to the first of 1648. But I was after the 1672 edition, as I needed a picture of its fascinating apocalyptic time chart for a paper I was preparing for publication. I wanted the caption to say that this was the same edition of Mede’s Works that Newton owned (and, presumably, used). The time chart forms part of my paper’s argument that, despite the common myth, Newton did not believe in a clockwork universe, but held to a dynamic cosmology similar to, and perhaps informed by, the arrow of time Newton encountered in biblical prophecy and Mede’s writings on the Apocalypse.

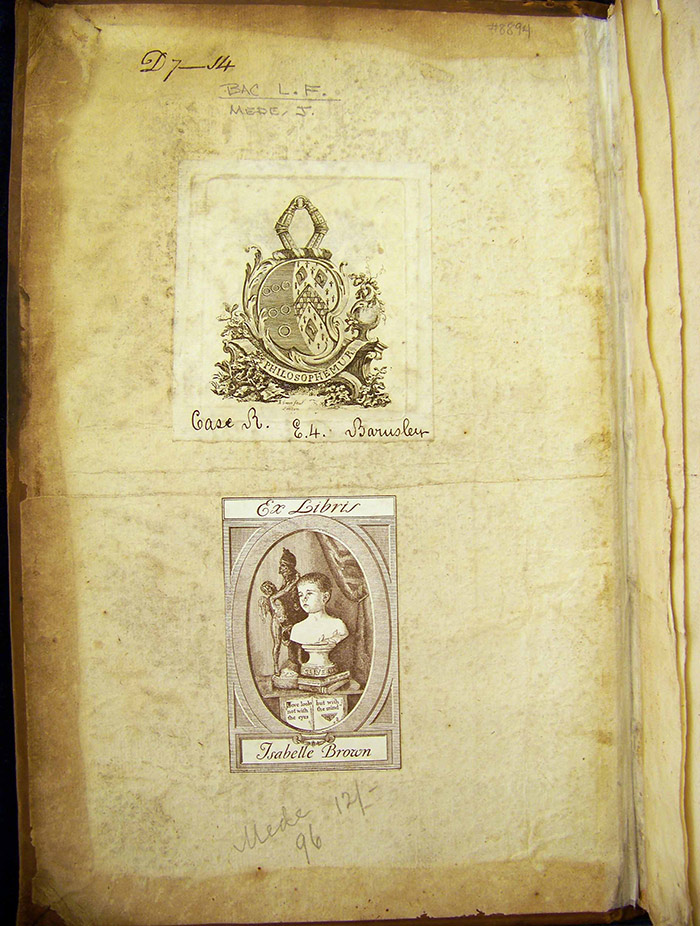

Close-up of the Musgrave bookplate in Newton’s copy of Mede’s Works (1672), showing the motto Philosophemur (“let us philosophize”) and the Barnsley Park shelf mark, “Case R. E.4. Barnsley.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As soon as I opened the book, however, I immediately realized that I held in my hands not merely the same edition we know Newton owned, but the very copy he owned. I felt momentarily disoriented as I beheld a Musgrave bookplate, usually a sure sign that a book came from Newton’s library, which resided in the Musgrave family’s home from 1778 to 1920. A quick check of John Harrison’s ever-helpful Library of Isaac Newton (1978) confirmed the precise details of the Musgrave shelf mark written above and to the left of the bookplate.

How did Newton’s ownership of this book escape detection at The Huntington? The process that obscured Newton’s ownership of this book takes us back a century or more. When half of Newton’s library was sold for auction in 1920, the Musgrave family had either lost track of its Newtonian provenance or hadn’t thought it a matter of significance. Thus the books were sold for a song and entered the rare book trade without Newtonian associations. Newton’s copy of Mede passed from a collector named Isabelle Brown to the former Bacon Library at Claremont Colleges before arriving, in 1995, at The Huntington—all without the great man’s name associated with it.

Barnsley Park in Gloucestershire, England. The stately country home of the Musgrave family when Newton’s library resided there from 1778 to 1920. Photograph by Stephen Snobelen, July 2008.

Another reason the book’s ownership became obscure: the bookplate does not bear the Musgrave family name, only the motto Philosophemur. Coupled to this is the fact that the person who long ago wrote the shelf mark, “E.4. Barnsley,” wrote the “n” like a “u,” and thus it entered the catalog as “Barusley.” As a result, the connection with Barnsley Park in Gloucestershire, England, where Newton’s library resided from 1778 to 1920, was masked. When you look at the shelf mark, I think you’ll agree that it looks more like Barusley than Barnsley.

Newton’s Naughty Dog-Ears

But what really cemented the Newtonian provenance of The Huntington’s book is the many signs of dog-earing. This was Newton’s preferred method of page marking, and scores of extant books from Newton’s 2,100-volume library bear these distinctive dog-ears. With just a few minutes before books were recalled in the Ahmanson, I did a quick survey of the volume and found meaningful dog-ears marking themes in Mede’s writings that we know Newton was passionate about from his own theological manuscripts.

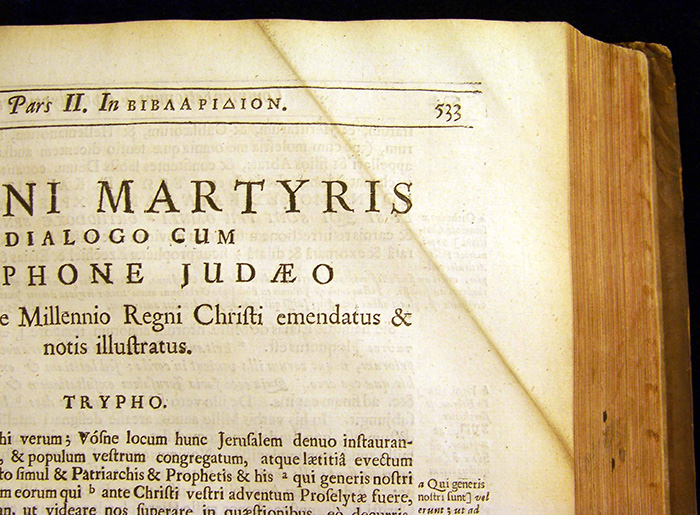

The outside fold of a dog-ear marking Justin Martyr’s testimonies about the Millennium in Newton’s copy of Mede’s Works (1672). The accumulated dirt on the fold is evidence that Newton kept the dog-ear down for many years. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

After reluctantly returning the book, I sent e-mails to several Newton colleagues around the world. Did anyone know that The Huntington possessed Newton’s lost copy of Mede? No, this was news to everyone. The following week, I sent pictures of the bookplate and dog-ears to this same group of historians. All agreed, this was the real McCoy: a bona fide Newton-owned book. When I told members of the Library staff, they were surprised and delighted.

The process of identifying and learning more about Newton-owned books and their history continues to involve a fruitful collaboration between researchers and librarians, such as the professionals here at The Huntington. Now that Newton’s personal copy of Mede has been identified, it can be studied along with The Huntington’s other 15 Newton-owned books. The main goal will be to cross-reference the dog-ears with Newton’s theological papers. This project has already begun.

At the end of his first chapter in Library of Newton, Harrison recalls how the book dealer Heinrich Zeitlinger deplored Newton’s practice of dog-earing, disdainfully labeling it “naughty.” But what to a book dealer is unsightly is to a historian a source of insight. I have now done a full survey of dog-ears in Newton’s copy of Mede’s Works: there are 60. Newton was a very naughty boy. And for the sake of scholarship, we’re glad he was.

Inside front cover of Newton’s copy of Mede’s Works (1672), showing the Musgrave shelf mark “D7—14,” the Musgrave bookplate and the bookplate of subsequent owner Isabelle Kittson Brown. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Stephen D. Snobelen is associate professor of History of Science at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He is currently on sabbatical and a Dibner Research Fellow in the History of Science and Technology at the Huntington Library.

NOTE: An earlier version of this post had indicated that Newton's library had resided in the Musgrave family's home from 1788 to 1920. The correct date range is 1778 to 1920.