Posted on Tue., June 9, 2015 by

The exhibition “Magna Carta: Law and Legend, 1215-2015” runs from June 13–Oct. 12 in the Library’s West Hall. We asked Tim Harris, professor of European History at Brown University and the 2014–15 Fletcher Jones Foundation Distinguished Fellow at The Huntington, to share his memories as an English youth in the environs of Runnymede—an area along the River Thames in the County of Surrey where King John signed Magna Carta in 1215—and reflect on the historical significance of the "Great Charter.”

View of the Magna Carta Memorial, Runnymede, Surrey. The memorial marks the spot in England where Magna Carta was sealed in 1215. Photograph © National Trust/Andrew Butler.

There are some dates in English history that are firmly imprinted on every English schoolchild’s mind. One is 1066—the year of the Battle of Hastings, which signified the beginning of the Norman Conquest of England, when English history really began. Another is 1939, when Nazi Germany invaded Poland and triggered World War II. And then there’s 1215—the year King John signed Magna Carta.

As my mother impressed on me at an early age, “Magna Carta was signed at lunchtime.” (We always had lunch at 12:15.) Where the Magna Carta was signed, Runnymede, was also firmly impressed on me as a youth. At my grammar school in nearby Egham, Surrey, our cross-country course took us along Runnymede before heading up and down Coopers’ Hill, and past the Magna Carta memorial, on our way to the finishing line.

Illustration of King John and the barons at Runnymede from Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1577. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

I cannot say it was my experience of running at Runnymede that inspired my love for history. Normally during “Games” we played football, the sport we English play with our feet. Cross-country seemed like punishment. The course was often waterlogged; there were cows—and cowpats—in the third field; and Coopers’ Hill was really quite daunting. Besides, history is all around one in England. It’s an old country. We had to buy our school uniforms from a shop opposite Windsor Castle—originally a Norman motte and bailey construction. Rather, it was an inspiring teacher at my school in Egham who developed my fascination for the academic discipline of history, and in particular for 17th-century English history, England’s century of revolutions.

Magna Carta has always been seen as an important foundational document of English constitutionalism. (It is a misconception that England does not have a written constitution; it is just written down in lots of different places.) Among other things, Magna Carta guaranteed the right to a trial by jury and that no one should be imprisoned or dispossessed of their property except by due process of law. It was reconfirmed many times during the later Middle Ages, and it acquired a powerful symbolic significance during the revolutionary upheavals of the 17th century.

Parliamentarians appealed to Magna Carta when criticizing royal government. Both King James I (1603–25) and King Charles I (1625–49) were accused of violating its provisions by raising taxes without consent and imprisoning people without due cause. Yet not just kings could fall foul of Magna Carta. Radicals complained that Parliament’s Conventicle Act of 1670 was in breach of Magna Carta by allowing Protestant nonconformists to be convicted without a jury trial. Political conservatives also appealed to Magna Carta, as the symbol of England’s commitment to the rule of law. Even the Stuart monarchs of the 17th century acknowledged that they were obliged to rule according to law.

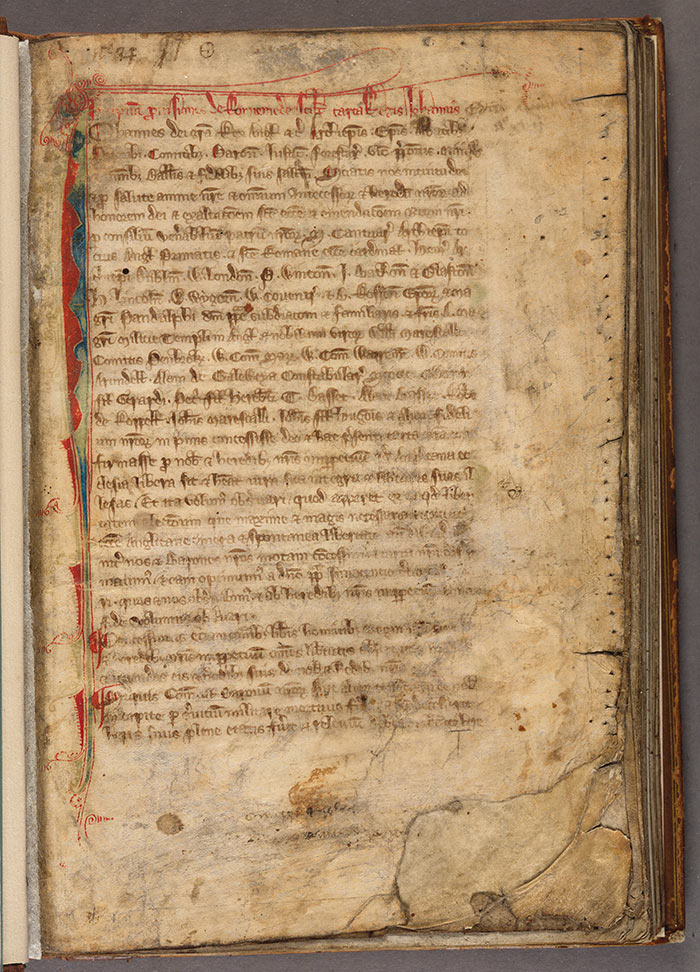

Rare draft of the Magna Carta, Laws & Statutes, England, 13th century. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

However, laws had to be passed, and taxes voted, by the king and Parliament. In the 1640s, Parliament went to war with King Charles I, enacted laws and collected revenues without the king’s consent, and then, in 1649, executed the king, abolished the House of Lords, and set up a republic. Oliver Cromwell ran the country for much of the 1650s backed by a standing army. When monarchy was restored in 1660, the years of civil war and Interregnum came to be seen as a period of unconstitutional government, when Magna Carta had been flouted. Ultra-royalists under King Charles II (1660–85) insisted that only by defending the prerogatives of the crown could the rule of law be guaranteed and Magna Carta upheld.

As England divided into two parties towards the end of Charles II’s reign, both Whigs (parliamentarians) and Tories (ultra-royalists) sought to represent themselves as defenders of Magna Carta, alleging that their opponents threatened to undermine it. In short, both sides claimed that English liberties were safe with them.

When Charles II’s successor, James II (1685–88), tried to set up his royal prerogative above the law, disillusioned Whigs and Tories united to bring him down and impose new constitutional constraints on future English monarchs through their Declaration of Rights of 1689 (subsequently enacted as the Bill of Rights).

As Sir Edward Coke had predicted back in 1628, “Magna Charta is such a fellow, that he will have no Soveraign.”

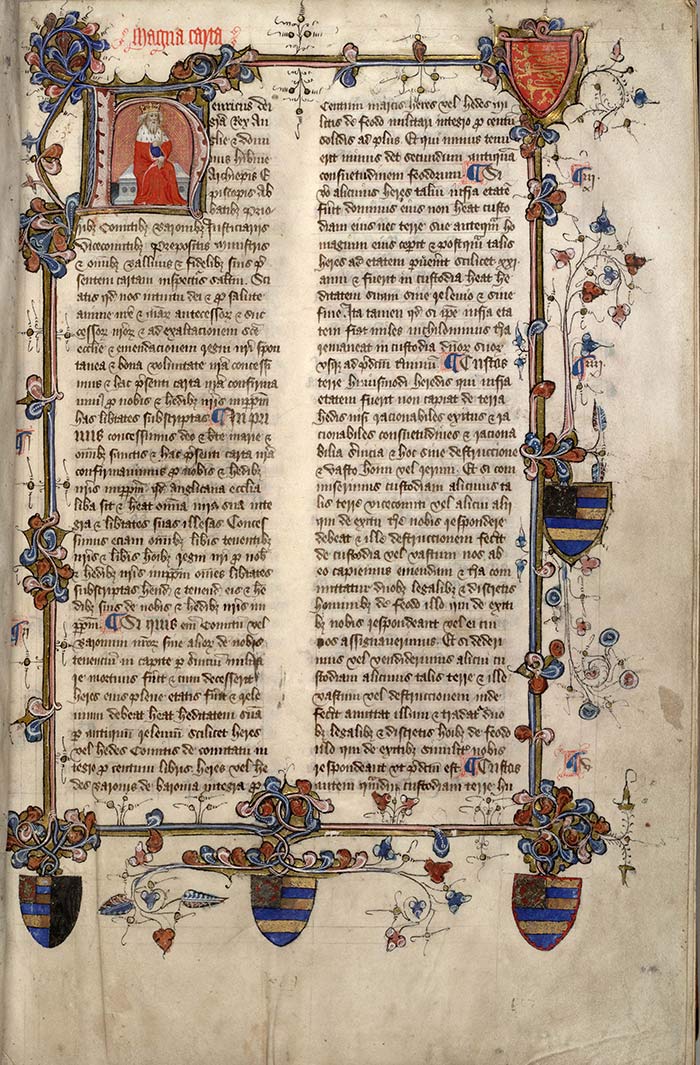

The Magna Carta reissued in 1225, Statutes. England, 15th century. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can listen to Tim Harris’ Distinguished Fellow Lecture, “Britain’s Century of Revolutions Reconsidered,” at iTunes U or download it directly here. His most recent book, Rebellion: Britain’s First Stuart Kings, 1567–1642, is available from Oxford University Press.

Tim Harris is Munro-Goodwin-Wilkinson Professor in European History at Brown University and the 2014-15 Fletcher Jones Foundation Distinguished Fellow at The Huntington.