Posted on Mon., June 22, 2015 by and

The Huntington’s Education staff recently formed a partnership with WriteGirl, a Los Angeles–based creative writing and mentoring organization that, according to the WriteGirl website, "launched in December 2001 to bring the skills and energy of professional women writers to teenage girls who do not otherwise have access to creative writing or mentoring programs." Huntington reader Ayana Jamieson is the founder of the Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network, a group of scholars, artists, activists, and fans devoted to the works of science fiction writer Octavia E. Butler, whose papers reside at The Huntington. Jamieson helped develop curriculum for the partnership, which included a one-day creative writing workshop at The Huntington using Butler materials. She shares a description of the day.

Using the prompt “If this goes on…,” teens from the Los Angeles–based organization WriteGirl tried their hands at writing speculative fiction. Photo by Martha Benedict.

Today, June 22, is the birthday of science fiction writer Octavia E. Butler (1947–2006), who specialized in speculative fiction, an umbrella term for writing that includes sci-fi, fantasy, horror, and superhero stories. For Butler, there were at least three main approaches to the genre. You could tell stories that explained “what if,” “if only,” or “if this goes on.”

During a workshop recently held at The Huntington, 60 professional women writers, serving as WriteGirl mentors, introduced Butler’s approaches to a group of 75 teen girls, ranging in age from 13 to 19. The girls spent a day touring The Huntington and learning about Butler’s personal history and literary style, and then tried their hands at writing.

The Pasadena-born Butler was the first black woman to gain recognition in the field of speculative fiction and, in 1995, became the first science fiction writer to win a MacArthur “Genius Grant.” Writing science fiction was more than a vocation for Butler. She embraced the genre’s limitless possibilities. As a black woman, the genre afforded her the opportunity to “write herself in,” creating a world in which she could live, even if she wasn’t entirely accepted in the larger, dominant society.

Octavia E. Butler near Mt. Shuksan, in the state of Washington, 2001. Photographer unknown. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Copyright Estate of Octavia E. Butler.

The idea of creating a world of their own choosing resonated with the teens. “I liked the ‘if this goes on’ approach,” said one teen. “If we keep treating our world like this, we will be extinct. I would like to see people treat plants the way they are treated here in The Huntington’s gardens.”

The teens divided into 10 groups, each following a different tour of The Huntington and hearing a script their mentors read that put them in a hypothetical situation. The groups took Butler’s works as starting points. One group, for instance, was called Acorn, the name of a community in Butler’s dystopic near-future California novel, Parable of the Sower. The Acorn group visited the Huntington Art Gallery, exploring the Thornton Portrait Gallery and using scenes, poses, and facial expressions from the paintings to build characters for their writing.

The teens and their mentors discussed Butler’s novel Parable of the Talents, as well as other works. Photo by Martha Benedict.

Then they visited the period rooms where Henry and Arabella Huntington once lived. They wrote from different points of view, including the role of the lady of the house, but also wrote a scene about being a servant to a wealthy family. (Octavia Butler’s own mother had been a domestic worker for much of her life.)

The teens speculated about a world they could create in their minds, where there was no hunger, poverty, disease, violence, war, or inequality.

As a black girl growing up during the era of Jim Crow laws that enforced segregation, Butler knew exclusion, rejection, and restrictions only too well. As a preschooler, she began telling herself stories to counter her loneliness and boredom and started writing them down; later, as a 12-year-old, she decided she would become a science fiction writer.

Butler’s characters are complex, never fully good or fully evil. They inhabit stories that weave together themes of power, gender, sex, race, and humanity. By depicting the trials of strong and complicated characters, her stories reveal powerful truths about society.

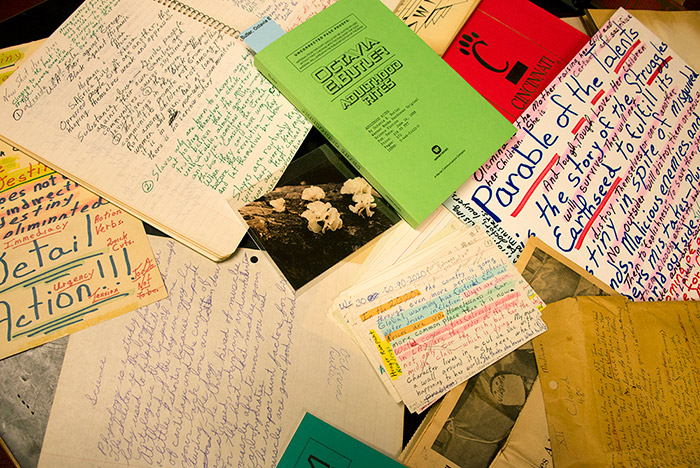

The Butler archive, which The Huntington acquired in 2009, includes more than 35 cartons (350 boxes) of correspondence, manuscripts, photographs, and ephemera. Photo by Kate Lain.

The boundless potential that Butler tapped into through her writing has attracted a strong and dedicated following among readers and scholars from all over the world. Natalie Russell, assistant curator of literary manuscripts at The Huntington, says that Butler’s archive of papers consistently attracts a high number of inquiries from scholars and fans, making it one of the most popular literary collections at The Huntington. A similar enthusiasm infused the teen girls at the writing workshop.

One participant remarked, “Learning about Octavia’s life really made an impression on me. Her courage and dedication were so inspiring, and I realize there’s no limitation to fiction writing.”

For teen girls facing challenges that they have little control over and cannot easily manage, creating a world of their own choosing is powerful and liberating. Butler knew this and gained prominence putting that idea on paper. Sadly, she left this world too soon, dying unexpectedly in 2006 at the age of 57.

Perhaps some of the teens who visited The Huntington will carry on her legacy.

Workshop participants listened to the story of Butler’s life, including her rise from humble beginnings to become a successful writer and recipient of the MacArthur “Genius Grant.” Photo by Martha Benedict.

Ayana A. H. Jamieson is the founder of the Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network and a reader at The Huntington.