Posted on Tue., Sept. 22, 2015 by

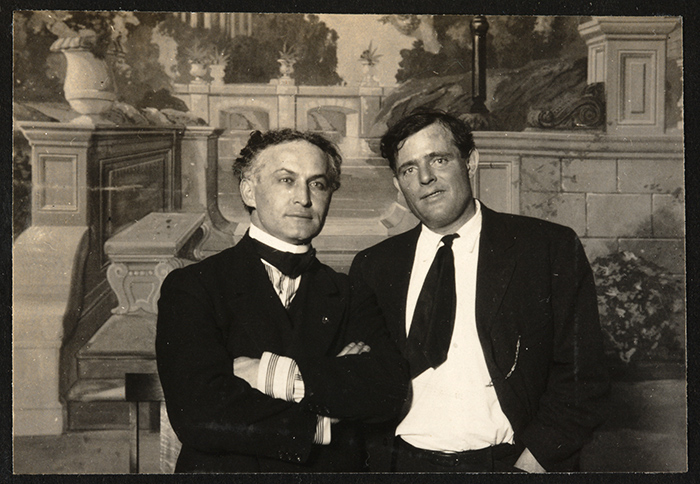

Harry Houdini (left) and Jack London—famous friends in the public eye. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Author Jack London found a kindred spirit in famed magician Harry Houdini, whose escape artistry London and his wife, Charmian, witnessed firsthand at the Oakland Orpheum on a November afternoon in 1915. The two men and their wives quickly became friends after a backstage visit, dining together at the Londons’ favorite local restaurant and again a few days later in the Houdinis’ hotel room on Thanksgiving Day.

What linked the two men? Each had committed bold acts of self-invention. Houdini was born Ehrich Weiss in Budapest in 1874, son of a rabbi, and changed his name in homage to a French magician. London was born John Chaney in 1876 and would adopt the surname of a new stepfather a few years later, more by circumstance than choice. Each would capture the public imagination of Americans at the turn of the 20th century—one for his mastery of escape and the other for his tales of adventure, borne from true-life exploits.

Compared to the persona created by Houdini, Jack London’s alter ego might have been the greater act of legerdemain—not so much for the way he overcame a hardscrabble childhood to become a literary sensation but rather for the dogged determination that helped him transcend a limited education to rub shoulders with the likes of Stanford president David Starr Jordan, let alone Harry Houdini.

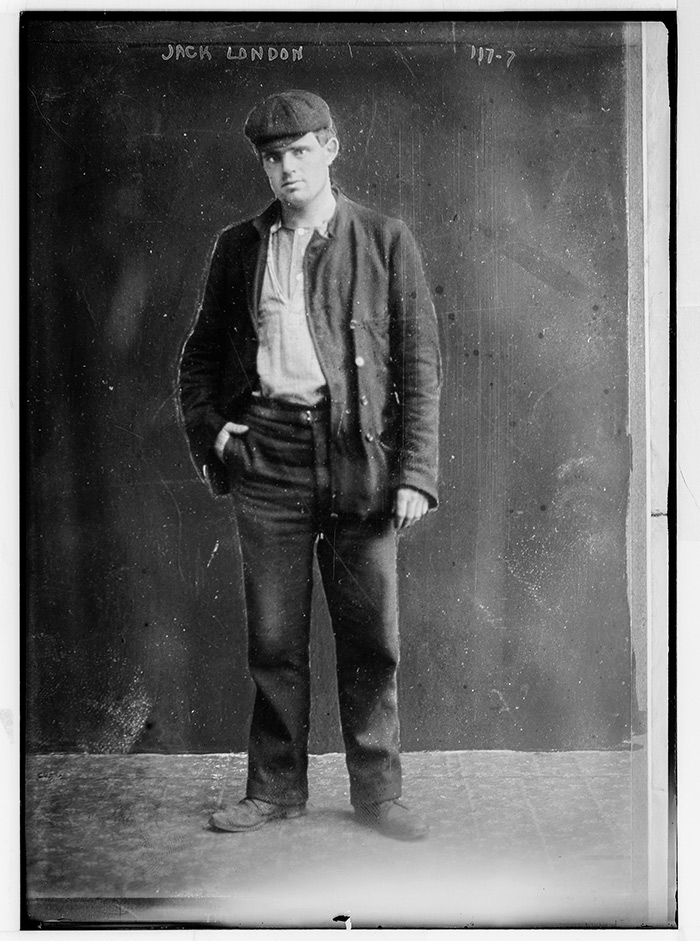

The sailor and workingman Jack London resembles his fictional but autobiographical Martin Eden. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In Jack London: A Writer’s Fight for a Better America, a new book published by University of North Carolina Press, Huntington reader Cecelia Tichi, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of English and professor of American studies at Vanderbilt University, posits that we should not confine ourselves to London the adventurer, travel writer, war correspondent, socialist essayist, or even prolific novelist. First and foremost, we should remember him as a public intellectual.

“London acted as a public intellectual through his fiction,” she says. “He set out to sway public opinion toward policies that would improve material life for all across the country—to abolish child labor, to raise wages, to create safe workplaces, and to support agricultural policies that would sustain the soil.”

One example of this mission can be found in Call of the Wild, which is far more than an adventure story. “[Jack] would reach the public through Buck,” writes Tichi, “his canine workmates, and the human masters who literally wield the whip. In political terms, Jack called it ‘class struggle…a class inequality, superior class and an inferior class (as measured by power).’”

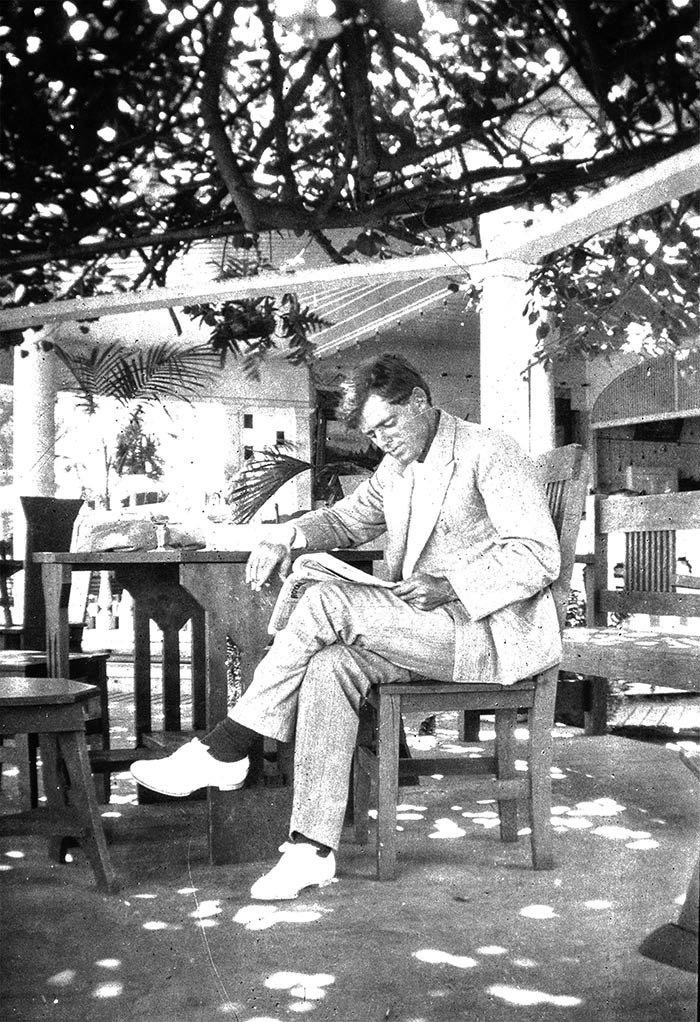

Jack London reads a newspaper to keep abreast of current events and glean ideas for new stories. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Tichi is the latest scholar to make use of the 50,000 London documents housed in the Huntington collection, joining the ranks of recent scholars such as London biographers Earle Labor and Jay Williams, Jeanne Campbell Reesman, and The Huntington’s own curator of literary manuscripts, Sara S. “Sue” Hodson. In this new study of London’s literary life, Tichi brings fresh insight to the collection of books, pamphlets, and newspaper clippings that London saved and marked in his own hand.

“These files contain the data he relied on to substantiate his arguments in the public sphere,” writes Tichi, “and were fundamental to his mission to ‘mould’ public opinion in order to realign the country’s political and social priorities.”

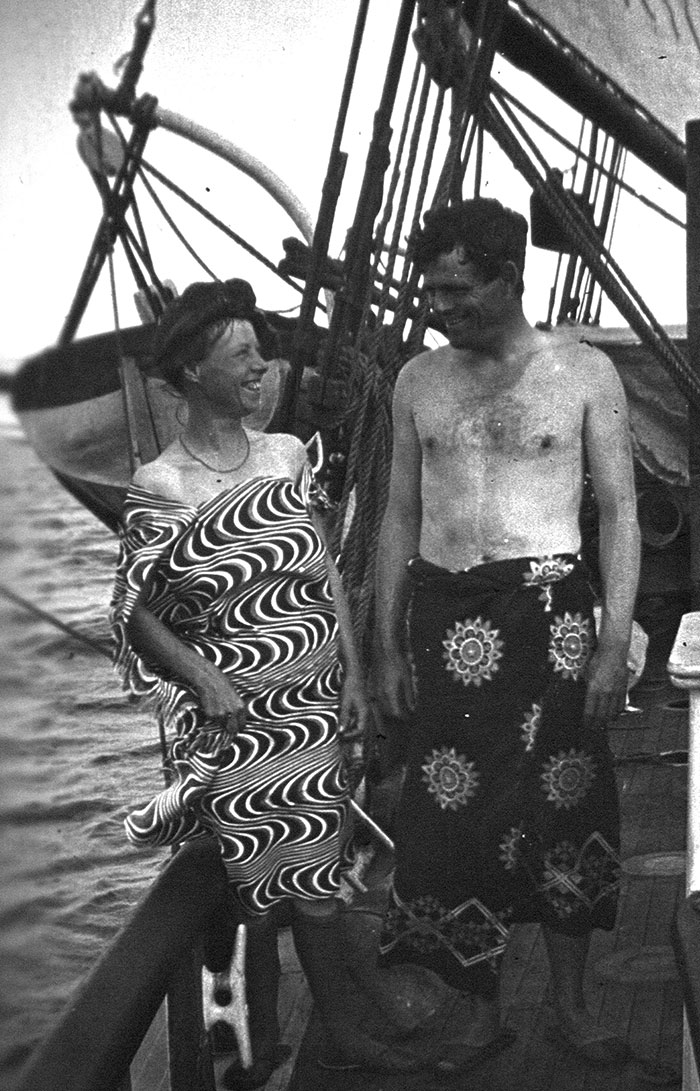

Tichi’s book features many photographs from The Huntington’s collection, and the enhanced e-book version contains archival motion picture footage, including a 14-minute clip showing the ruins from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. The apocalyptic scenes resemble the world London witnessed in Asia as a correspondent during the Russo-Japanese War and would inspire the catastrophic war zones of the fictional Chicago that he depicted in his dystopian novel The Iron Heel two years later.

Jack London, dressed in a lava-lava, with his wife, Charmian, in the South Seas. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Another clip depicts Harry Houdini escaping from a straightjacket—suspended upside down high above the bustling streets of New York City. The straightjacket is the ultimate symbol of oppression in London’s tour de force novel Star Rover, in which he depicted the brutal conditions of prison life in California. Before writing this book, Tichi tells us, London befriended a real-life ex-con to tell the story of a prisoner who survived solitary confinement by working himself into a trance and then transporting himself through time, space, and past lives. Tichi sees the novel as a thinly disguised political tract, with intersecting plotlines of straightjacket and spiritualism; it attracted the attention of reform activists as well as Houdini, who dabbled in his own version of mysticism.

London had yet another great act of escape up his sleeve, the autobiographical Martin Eden, a novel that tells the story of a brutish working stiff who infiltrates the bourgeoisie of turn-of-the-century Oakland, California. As Eden climbs out of the lower classes through his ambitions to become a writer, he falls in love with the upper-class Ruth Morse, giving London the opportunity to vent the frustration he felt when he navigated the colliding cultures of his two worlds.

“London draws you in,” says Tichi, “and he said, ‘My emotions have to become my reader’s emotions so that when I teach a lesson, my reader is with me and not on the other side.’” London drew criticism for having his protagonist, the enigmatic Martin Eden, slip into the sea with resignation and despair at the book’s conclusion. In her retelling, Tichi doesn’t pull off a rescue of Martin Eden as much as she revives Jack London, who should now endure in our minds as a true public intellectual.

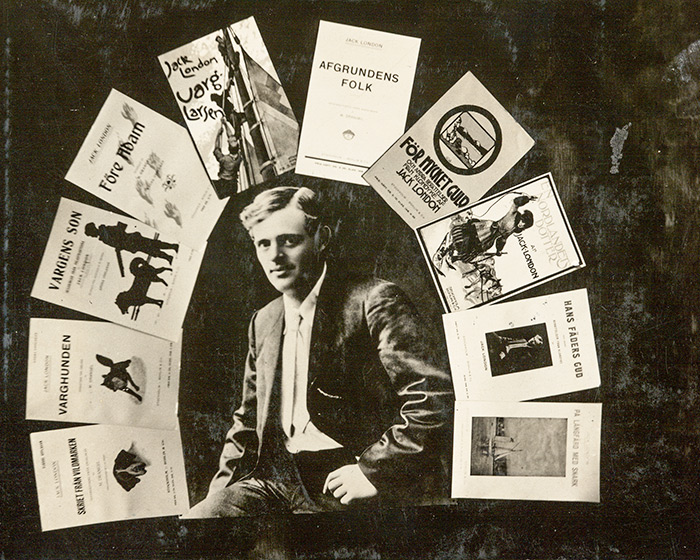

The world-famous author Jack London is surrounded by translations of his books. London was the first American author to earn $1 million. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can order Cecelia Tichi’s Jack London: A Writer’s Fight for a Better America, from The University of North Carolina Press website. The enhanced e-book version can be ordered for the iBook and Kindle.

You can read an article about Jack London’s photography, “Writing in Light,” in the Fall/Winter 2010 issue of Huntington Frontiers.

Related content on Verso:

To Build a Fire (Jan. 10, 2014)

The Star Rover (Jan. 12, 2012)

A Friend to Jack London (Sept. 15, 2011)

Matt Stevens is the former editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine. He is now managing editor at the USC Rossier School of Education.