The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Reading the Aftermath of Civil War

Posted on Wed., Oct. 28, 2015 by

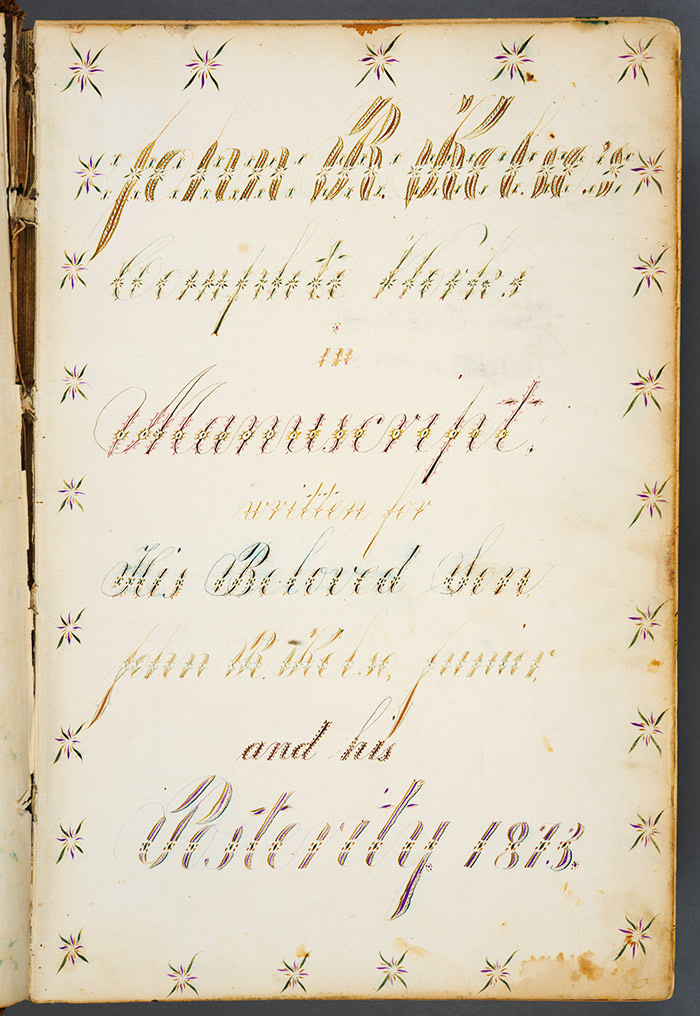

Title page of John R. Kelso, Complete Works in Manuscript, written for His Beloved Son, John R. Kelso, Junior, and his Posterity, 1873. John R. Kelso (1831-1891) was elected to the U.S. Congress from Missouri in 1864 and served in the turbulent postwar years of 1865–1867. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

I had the pleasure of attending “Ending a Mighty Conflict: The Civil War in 1864–1865 and Beyond,” a conference that took place at The Huntington last month. The lively talks by distinguished scholars reminded me of my recent encounters with the handwritten accounts of Civil War soldiers. Expressing noble sentiments, these soldiers called the war the “mightiest struggle ever recorded in the history of the world” and “the most stupendous tragedy ever enacted on the stage of time.”

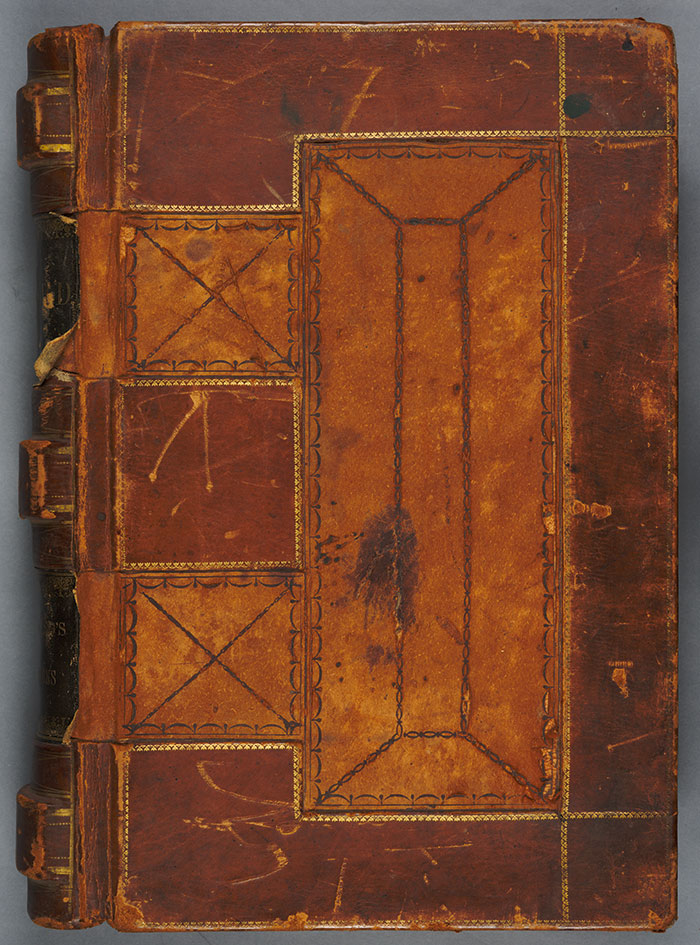

Such are the ornately inscribed words of John Kelso—a one-time Union soldier, educator, and politician from Missouri—who includes them in an oversized volume, bound like an enormous Bible, containing 800 pages of his handwriting. Propped on a “cradle” in The Huntington's Ahmanson Reading Room, the volume requires a scholar to stand on her toes to read the top lines and then crouch down to scan the bottom of each page. It would no doubt take many weeks of this exhausting exercise to read the volume in its entirety. (Happily, I won’t have to do this because Christopher Grasso, professor of history at College of William & Mary, will soon publish an authorized edition of Kelso’s Civil War episodes and a biography of Kelso himself with Yale University Press.)

Kelso’s political speeches introduce the volume, dedicated to “His Beloved Son” and to “his Posterity” in 1873. These speeches are at once effusive and intricate in their knowledge that the speaker faces an audience with many pro-slavery members. Before the war has ended, he speaks of the painful deaths on the battlefield where “wolves and vultures feast upon the unburied bodies of our slain.” The writing is so passionate and so convoluted that a reader can only be surprised when Kelso ends with an ambivalent request to run for political office.

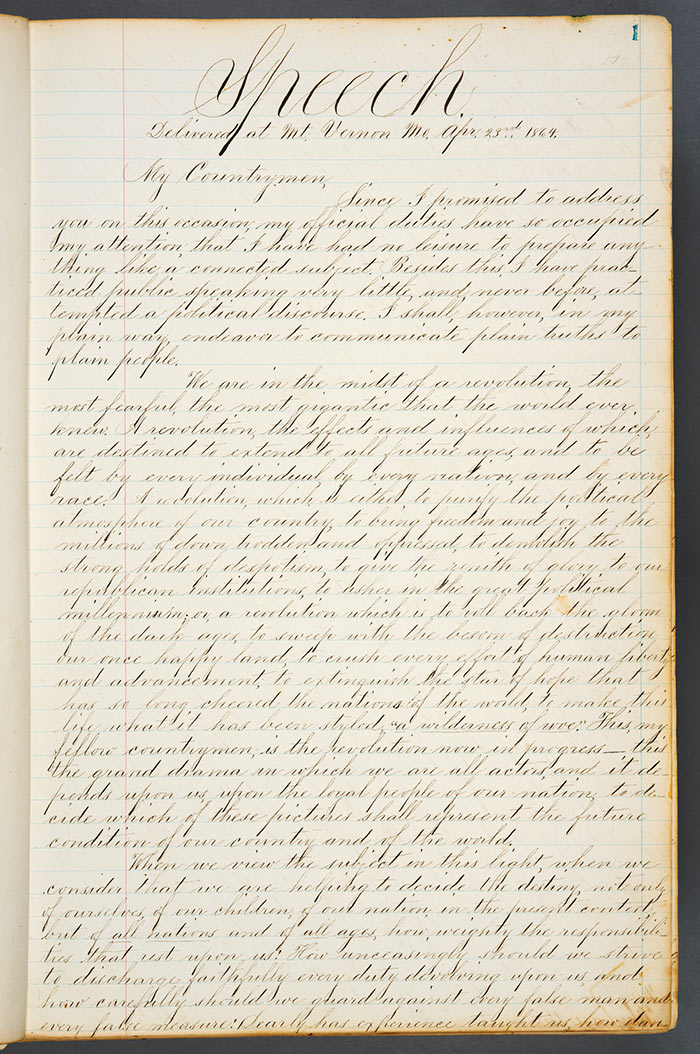

In a speech delivered at Mt. Vernon, Missouri, on April 23, 1864, John R. Kelso declared: “We are in the midst of a revolution . . . the effects and influences of which, are destined to extend to all future ages, and to be felt by every individual, by every nation, and by every race.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Kelso recognized that many listeners couldn’t follow him through all the ins and outs of the reactions to slavery that he at once catalogs and proposes. His racism is evident. Yet he hates slavery and believes in “equal rights.” He finds miscegenation horrifying. But he astutely notes that the loudest voices from the South emerge from communities where the procreative effects of slavery include lighter and lighter skin. His idea to deport all former slaves to Mexico has a certain terrible novelty.

The first speech recorded in the volume, one delivered while the war continued, is followed by a speech delivered just after the conclusion of the war. In the latter speech, Kelso repeatedly references Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost as a way to evince moral horror about the effrontery of Southerners who imagine that they should have the right to vote. Inspired by Milton, Kelso thinks the rebels should be in Hell. Sadly, for him, the North doesn’t have the divine power to place them there, for, as he puts it drily, “we lack that one little convenience.” After the war’s end, Kelso is scornful of the allegiance of former rebels. He writes: “They take the oath of allegiance as readily as they take bad whiskey.”

What can be hard to reconcile in such writing is the wonderful eloquence of moral outrage and the clearly horrified reaction to miscegenation. Kelso notes that many in his audience fear what for them would be the worst-case scenario—that their daughters would marry and provide them with offspring such that “certain devilish little mulattoes may be calling them ‘grand pap.’” Yet he notes that typically men with those fears know “their own proneness to mix with the kinky heads” and that the southern United States already shows an inclination toward an outcome in the face of which he professes at once outrage and horror. Scholars of the immediate postwar era and the perils and pitfalls of Reconstruction are confronting the dilemmas that Kelso forecast—that while slavery had officially ended, racist ideologies and their consequences would permeate the consciousness of the nation for decades to come.

The front cover of John R. Kelso’s oversized manuscript, bound like an enormous Bible, containing 800 pages of his handwriting. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Related content on Verso:

Turbulent End to Civil War (Sept. 15, 2015)

Lincoln’s Last Hours (April 14, 2015)

The Union Forever (March 31, 2015)

“Where Solomon Northup Was a Slave” (March 3, 2014)

VIDEO | Voices of the Civil War (Oct. 12, 2012)

The Civil War Lives (Oct. 25, 2011)

Mystic Chords of Memory (March 4, 2011)

Many Happy Returns (Feb. 16, 2011)

Shirley R. Samuels, professor of English at Cornell University, is the 2015–16 Los Angeles Times Distinguished Fellow at The Huntington. Her books include The Cambridge Companion to Abraham Lincoln, Reading the American Novel: 1780-1865, and Facing America: Iconography and the Civil War.