Posted on Mon., Oct. 19, 2015 by

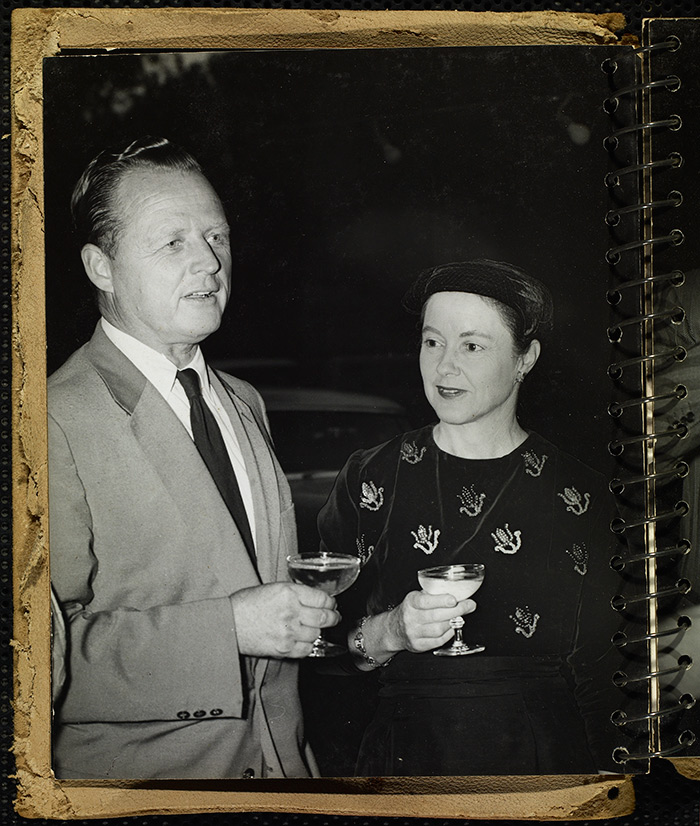

Millard Sheets and his wife, Mary Sheets, at a party related to the “Arts of Daily Living” exhibition at the Los Angeles County Fair in Pomona, 1954. Photo by Maynard L. Parker. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The documentary filmmaker Paul Bockhorst discovered the creative spark for his most recent film in 2011 when he visited The Huntington’s exhibition “The House That Sam Built,” a show focused on the furniture of mid-20th-century craftsman Sam Maloof and art made by members of his Pomona Valley circle, including Millard Sheets. For Bockhorst, the exhibition was a revelation.

“There was so much fine work, in such variety,” says Bockhorst. “I thought, ‘This is the moment I need to move forward to explore this same era.’” The result is the film Design for Modern Living: Millard Sheets and the Claremont Art Community, 1935-1975, which was screened at The Huntington on Oct. 4 with Bockhorst and some of the film’s subjects and collaborators present.

The documentary starts with Millard Sheets, a Pomona native who is best known to Californians for his mosaic murals in Home Savings and Loan buildings and to college football fans for the University of Notre Dame’s “Word of Life” mural, nicknamed “Touchdown Jesus” because of its depiction of Christ’s upraised arms. Bockhorst’s Design for Modern Living, however, concentrates on Sheets’ role as an educator. As founder and chair of the art department at Scripps College from 1936 to 1953, Sheets became the hub of an art community that produced a remarkable ripple effect.

Susan Hertel, a former student of Millard Sheets at Scripps College, composed this gouache study for the mosaic installed on the Home Savings and Loan building in Temple City, Calif., 1984. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“Millard Sheets was a visionary leader who developed at Scripps College one of the strongest art programs in Southern California in the postwar period,” says Harold B. ‘Hal’ Nelson, The Huntington’s curator of American decorative arts and a frequent commentator in the film.

“Sheets believed that all forms of artistic expression—from painting and sculpture to ceramics, enamels, mosaics, and architecture—were equally valid. He also recognized that it was important to expose young students to practicing artists rather than academics and assembled at Scripps an extraordinarily diverse community of artists. All this is chronicled in Paul Bockhorst’s marvelous film,” says Nelson.

Sheets brought to Scripps full-time faculty and visiting artists from a wide spectrum of disciplines and aesthetics. Freedom and openness were hallmarks of the department. As one of the film’s two dozen profiled artists says, “There was no ‘fine art,’ no ‘decorative art,’ there was just ‘art.’” Artists such as the 101-year-old ceramist Harrison McIntosh describe in vivid terms the camaraderie they experienced more than half a century ago and the “constant stimulus” of informal gatherings in Scripps’ Seal Court.

John Edward Svenson (1923–), Sea Sprite, 1967, redwood, 20 x 52 1/2 x 14 in. Gift of David and Kazumi Svenson in memory of Louise “Lou Ann” Svenson. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One of the film’s interviewees, Martha Longenecker, started out to be a painter but was so impressed by two visiting ceramists from Japan that she switched to ceramics. She became well known in that field, and she went on to found the Mingei International Museum in San Diego, with its collection of ancient and current folk art. She recalls Sheets as “so full of the joy of life, so positive.”

Another interviewee, sculptor John Svenson—who, like many of the male artists in the Claremont community, attended Scripps College after World War II on the GI bill—rejected bronze as his material for sculptures in favor of redwood. His Sea Sprite, featured prominently in the film, is in The Huntington’s art collection.

Sheets’ influence didn’t stop at Scripps. Starting in 1937, Sheets staged exhibitions in the Fine Arts building at the Los Angeles County Fair that were on a scale of those at the nation’s largest museums. One of the most memorable was the 1954 “Arts of Daily Living” exhibition, a collaboration between Sheets and the magazine House Beautiful, featuring 22 model rooms of the latest in modern design with works by Pomona Valley artists. (You can read more about the “Arts of Daily Living” exhibition on Verso here.)

After the film screening, attendees strolled to The Huntington’s Stewart R. Smith Board Room to view in person Sheets’ Mural for the Home of Fred H. and Bessie Ranke of 1934, created a couple of years before Sheets started teaching at Scripps College. The crowd stood rapt before the expansive and subtly hued panorama of trees and mountains—the sort of California landscape that inspired Sheets and helped shape his artistic vision.

Mural for the Home of Fred H. and Bessie Ranke, 1934, by Millard Sheets. Gift of Larry McFarland and M. Todd Williamson. Depicting a bucolic California landscape of stylized hills and trees, the mural was painstakingly removed and conserved before being installed in the Stewart R. Smith Board Room at The Huntington. Photo by Tim Street-Porter. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can read an article about Millard Sheets and his Mural for the Home of Fred H. and Bessie Ranke in the Spring/Summer 2015 issue of Huntington Frontiers.

The film Design for Modern Living: Millard Sheets and the Claremont Art Community, 1935-1975 will be screened throughout the day at the Padua Hills Art Fiesta on Nov. 1.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications at The Huntington. She is a Los Angeles-based communications consultant.