Posted on Fri., July 22, 2016 by

In commemoration of the centennial of the creation of the National Park Service, The Huntington is mounting two related exhibitions. The first part, “Geographies of Wonder: Origin Stories of America’s National Parks, 1872–1933,” is on view through Sept. 5, 2016. A second exhibition, “Geographies of Wonder: Evolution of the National Park Idea, 1933–2016,” runs from Oct. 22, 2016 to Feb. 13, 2017. We also celebrate the writer Jack London, whose papers reside at The Huntington and who was no stranger to the wonders of our nation’s natural beauty. (Please note that the images in this blog post are not on view in the “Geographies of Wonder” exhibition.)

Snark, the vessel on which the Londons and their crew attempted an around-the-world trip, at anchor in Apia, Samoa, 1908. Photo by Jack London. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Snark, the vessel on which the Londons and their crew attempted an around-the-world trip, at anchor in Apia, Samoa, 1908. Photo by Jack London. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.Author Jack London (1876–1916) is best known for adventures in the Klondike, especially as seen through the canine eyes of Buck, hero of his novel The Call of the Wild. But while London traversed the Klondike in search of gold in 1897, it was not his only adventure. London and his wife, Charmian Kittredge London, visited eight of today’s national parks, most of them together.

London traveled to Yosemite in 1895 at the age of 19, climbing from the valley to the rim near the monolithic El Capitan with five friends. His short story “Dutch Courage” chronicles an attempted ascent of Yosemite’s famous Half Dome.

Charmian Kittredge had visited Yosemite even earlier, in 1890, before she was married to London. A college graduate working as a secretary, Kittredge had her own income and was extremely independent for a woman of her day. An avid horseback rider, she was one of the first women in the Bay Area to ride—scandalously—astride! She would become the perfect companion for London. As far as we know, her regular diary keeping didn’t begin until 1900, but she did bring back photographs of her Sierra trip.

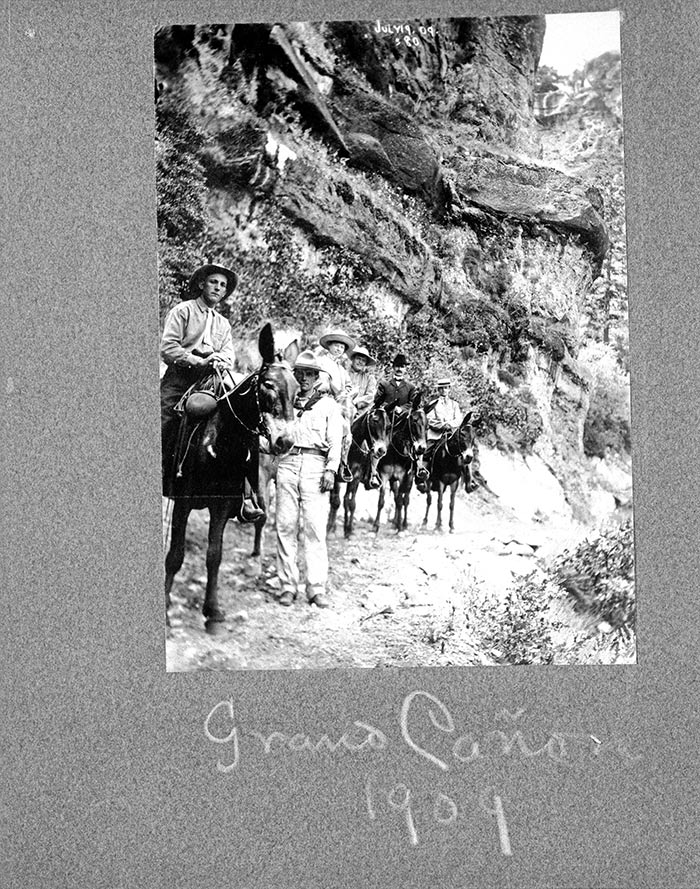

Charmian London and Jack London (third and fourth from the left) on a guided mule trip into the Grand Canyon. Photographer unknown, 1909. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Charmian London and Jack London (third and fourth from the left) on a guided mule trip into the Grand Canyon. Photographer unknown, 1909. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.London himself would become a phenomenal photographer, documenting the places he visited and the people he met all over the world.

In 1907, the Londons set off on one of their greatest adventures, a seven-year sailing trip around the world in their new yacht, the Snark. Ill health and a number of other difficulties forced them to abandon the circumnavigation after less than two years, but not before they and their crew had sailed to Hawai’i and the South Pacific. Their travels took them to three future parks.

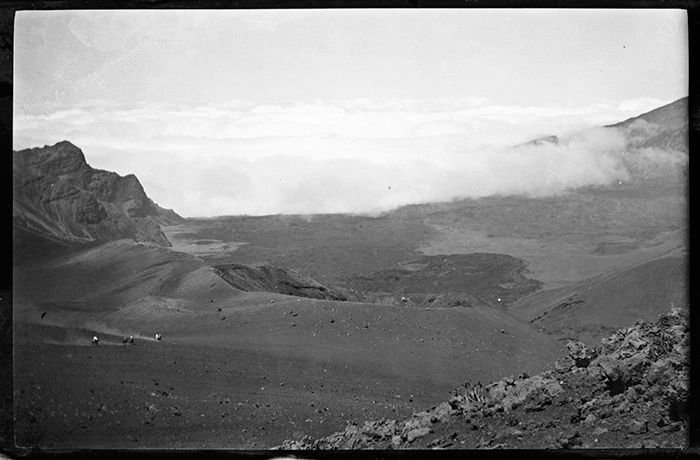

In Hawai’i, the Londons visited the “House of the Sun,” the great crater of Haleakalā on Maui, which celebrates its centennial as a national park this year. Charmian later described the sight:

“More than twenty miles around its age-sculptured brim the titantic [sic] rosy bowl lay beneath; seven miles across the incredible hollow our gaze traveled to the glowing mountain-line that bounds the other side, and still above . . . we could not believe our sight that was unprepared for such ravishment of beauty.”

Yosemite Valley as photographed by Charmian Kittredge, 1890. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Yosemite Valley as photographed by Charmian Kittredge, 1890. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.On the Big Island, the Londons hiked Mauna Kea and Kilauea, the great volcanoes of Volcanoes National Park. Staying at the famous Volcano House, London commented in the register, “It is the pit of Hell.” Nonetheless, the Londons returned at least two more times on future visits to the island. Hawai’i would become one of their favorite places, which Charmian would recall in her book Our Hawai’i.

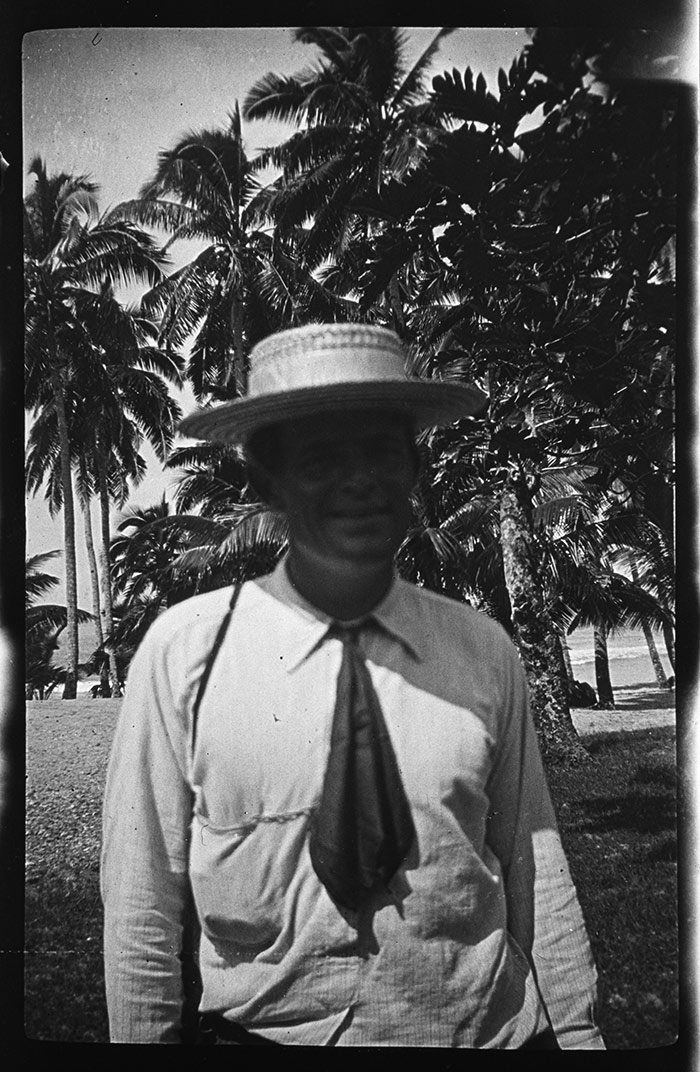

Sailing from Hawai’i, the Snark crossed the equator and stopped at numerous islands in the South Pacific. On April 29, 1908, the Londons anchored off the island of Manua, in American Samoa, and stayed in the area for a week. They watched a woman making tapa cloth (a decorative cloth made from bark) and visited the grave of Robert Louis Stevenson. The National Park of American Samoa includes the islands of Tutuila, Ta’u, and Ofu—designated a national park in 1988. At almost 5,000 miles from the mainland, it’s one of the least visited parks in the nation, not quite topping 14,000 visitors last year. Of Ta’u, Charmian wrote: “Our Carmel never flaunted more brilliant turquoise and emerald than do the glorious breakers of Ta’u.”

Clouds over the crater of Haleakalā, Maui, 1908. Photo by Jack London. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Clouds over the crater of Haleakalā, Maui, 1908. Photo by Jack London. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.By the time the Londons reached the Solomon Islands, they were weary and in poor health, and decided to cut short their sailing adventure. They returned from the South Seas by steamer to New Orleans in 1909 and then took the train back to California. Along the way, they stopped to see the great wonder of the Southwest, the Grand Canyon. They rode down into the Canyon on mule, stopping for the signature trail photograph. Afterward, they spent the night on the South Rim at the luxurious El Tovar Hotel and then boarded the train to resume their journey home. The Grand Canyon became the 15th national park in 1919.

Throughout their time together, the Londons enjoyed a life of adventure. They explored Mount Desert Island in Maine in 1905, home to the future Acadia National Park; Death Valley in 1907; and Crater Lake, the only location that was already a park when they visited, in 1911. (Crater Lake National Park was created in 1902). At Crater Lake, they slept in a tent at Camp Arant, the headquarters for the park. In her diary, Charmian compared the crater to Haleakala: “. . . like a wet Haleakala, was way ahead of all expectation and indescribable. Such blue, such rosy and golden rim.”

London’s peregrinations would inspire him to write some of the great novels and short stories in American literature. One hundred years after London’s death, national parks continue to inspire wonder, hosting more than a quarter of a billion people each year and providing visitors with memories that fuel their own special stories.

Jack London in Samoa, wearing a straw hat. Photo attributed to Charmian London, 1908. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Jack London in Samoa, wearing a straw hat. Photo attributed to Charmian London, 1908. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.Related content on Verso:

Jack London and the Rose Parade (Jan. 1, 2016)

Jack London, Public Intellectual (Sept. 22, 2015)

To Build a Fire (Jan. 10, 2014)

The Star Rover (Jan. 12, 2012)

A Friend to Jack London (Sept. 15, 2011)

Natalie Russell is The Huntington’s assistant curator of literary manuscripts.