The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Visualizing the Anatomy of the Eye

Posted on Wed., June 14, 2017 by

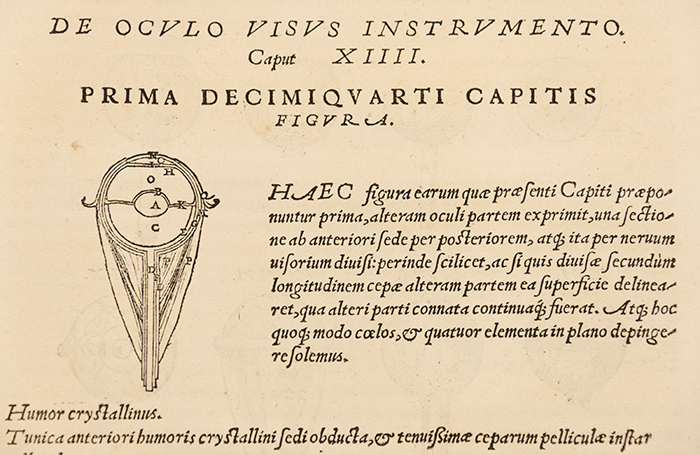

Vesalius’s first cross-sectional image of the eye, from Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), 1543. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

As a historian of science, I’m fascinated with pictures that help make sense of past scientific ideas and practices. The Huntington’s vast collection of rare 16th-century science books document how intellectuals of the day perceived the eye and the process of sight. Chief among these works is the groundbreaking anatomy book De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body) by the Flemish-born anatomist and physician Andreas Vesalius (1514–64).

De fabrica was printed in 1543 in Basel, Switzerland, and, with its incredible woodcut images based on the burgeoning practice of human dissection, it marked a major development in the history of anatomy. Readers might be familiar with the book’s famous muscle men or the memento mori of a skeleton contemplating a skull. Although less well known, Vesalius’s detailed diagrams of the eye were among the first in a printed anatomical treatise. His cross-sectional diagram would become the model for almost all other visual representations of the eye in anatomy and optics until the mid-17th century.

Vesalius tells us that he drew a similar diagram for his students prior to performing an ocular dissection. A real eye has many fluid, transparent parts that are difficult to grasp (literally and conceptually) in a dissection, so Vesalius used a visual aid to bring order to the messiness of the anatomized eye—he was telling his students and his readers what they were supposed to see. But, by visualizing the eye before his students (or readers) would see an anatomized eye itself, what sort of order was he imposing?

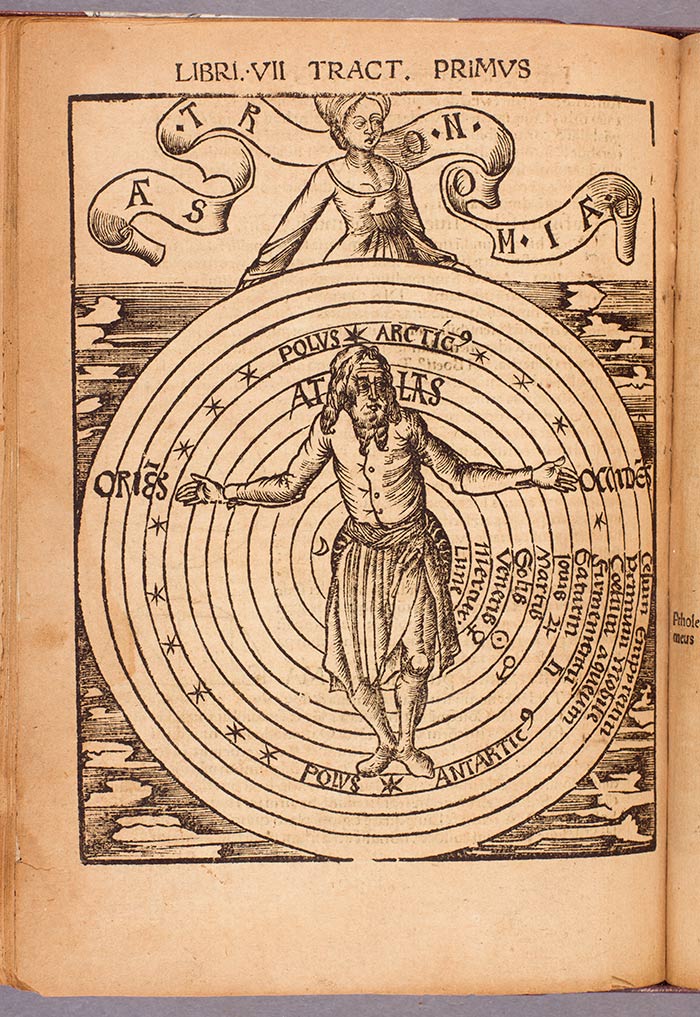

Diagram of the cosmos, from Gregor Reisch, Margarita philosophica (Pearl of Wisdom), 1504. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The eye Vesalius depicts in De fabrica was very much a product of the image-making culture of his age. Vesalius writes that the eye can be compared to the cosmos—an earth-centered cosmos, that is. The year 1543 was revolutionary for science. Nicolaus Copernicus, in the same year, published De Revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), which had the earth revolving around the sun, rather than the reverse. Copernicus’s heliocentrism, however, took hold slowly. Geocentrism was the order of the day.

So Vesalius addresses readers who would be familiar with images of an earth-centered cosmos, for instance those found in the most popular university textbook in the first half of the 16th century, Gregor Reisch’s liberal arts textbook Margarita philosophica (Pearl of Wisdom), also in The Huntington’s collections. Vesalius draws upon this scheme and puts the lens at the center of the eye. Many implications from this concept of the cosmos are transferred over: for example, just as the universe was constructed according to a divine plan, so too was the eye.

Vesalius did not invent a new theory of vision. Most people at the time believed that the purpose of the ocular lens was not to refract rays of light and color but to receive and capture them. The basic idea was that, if what we see are the colors of things, then what we see with must be uncolored—that is to say, it must be transparent. This theory of perception, hailing back to Aristotle, ruled out the retina: it was too dark, too rough, too colored. The central place of the lens in Vesalius’s diagram showcases its central place in the visual theory of the time.

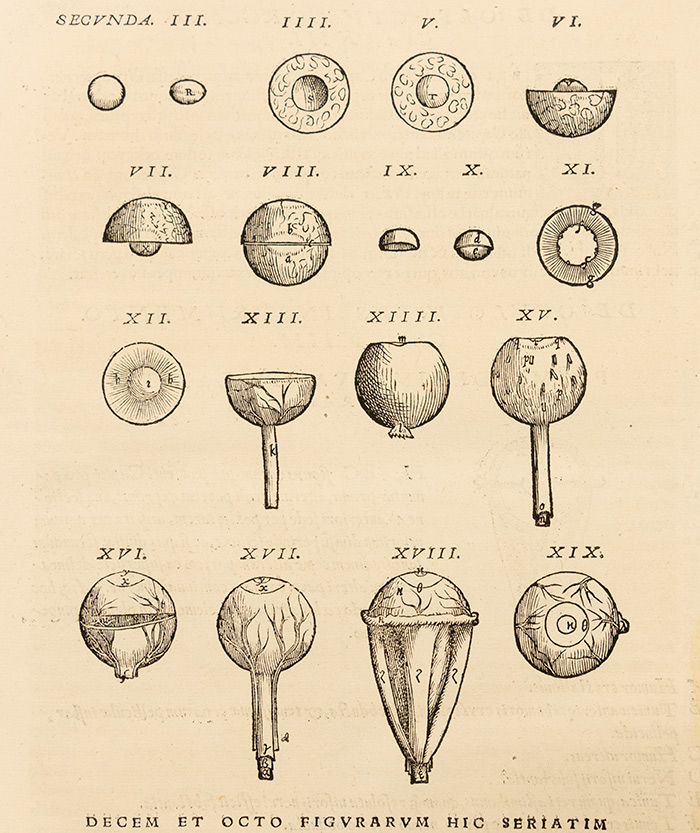

Detail from Vesalius’s idealized depiction of the shapes and sizes of the parts of the eye, and how they fit together. From Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), 1543. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

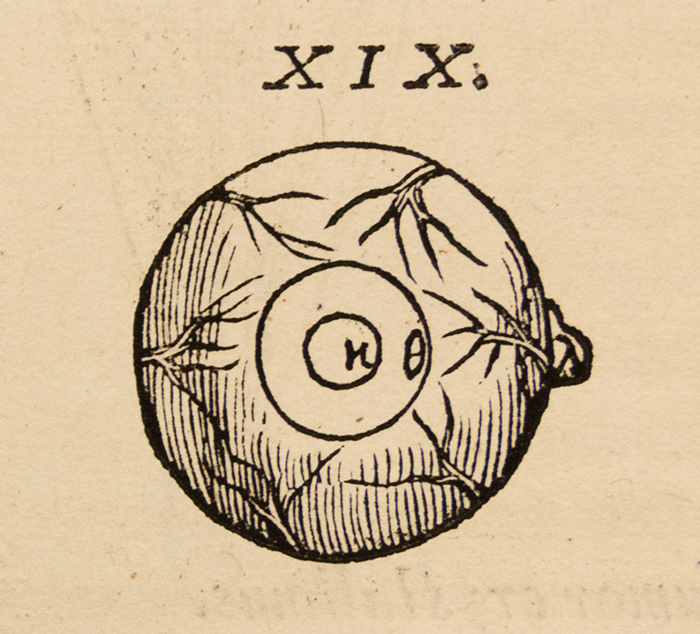

Vesalius also provides a “deconstructed” image, which might be thought of as assembly instructions for Nature herself. At the top-left, you can see a lentil-shaped part of the eye—in fact, the English word lens comes from the Latin word for lentil. Reading from top-left to bottom-right, one sees the eye being constructed piece by piece. Notice that Vesalius rotates the parts to show them from different angles, helping us to generate a three-dimensional picture in our minds. Once we have built up a mental model, we can then scan from bottom-right to top-left to understand how to dissect the eye, instructions for which Vesalius gives in a subsequent chapter. Keep in mind that these are images of fluid humors and delicate membranes—what he shows is clearly not what one would actually see in a dissection.

Vesalius’s images were the first, in print, to try to accurately depict the relative sizes, shapes, and positions of the eye and its parts. But, paradoxically, to be faithful to anatomy, he had to present an ideal: he showed how to construct or dissect an eye in one’s mind. These and other images in the magnificent collection of books at The Huntington are windows into the world—the microcosm and the macrocosm—of the 16th century.

Detail from Vesalius’s idealized depiction of the shapes and sizes of the parts of the eye. From Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), 1543. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

Tawrin Baker is the 2016–17 Dibner Fellow in the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington. He was a Mellon Postdoctoral Associate in the History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh for 2015–16 and will be a postdoctoral fellow in the Visual Studies Program at the University of Pennsylvania for 2017–18.