Posted on Sun., April 19, 2015 by

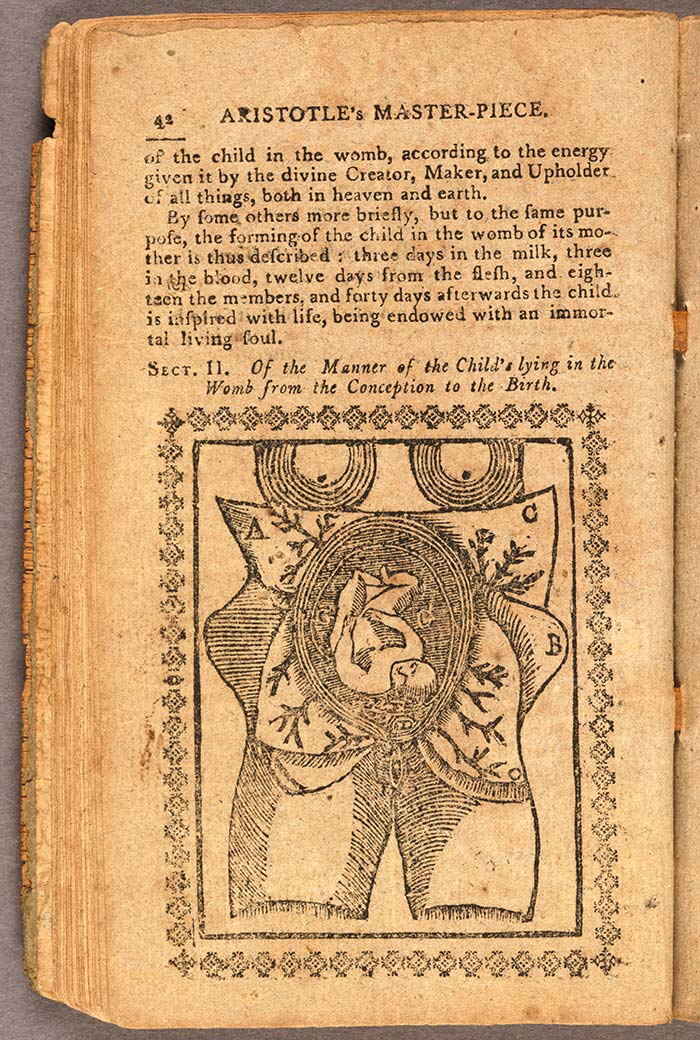

Aristotle’s Masterpiece provided ordinary readers access to images such as this one, which depicts the position of a baby in the womb, as well as access to practical instructions about maintaining health during pregnancy. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Aristotle’s Masterpiece was the bestselling book about sex and reproduction on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean from the late 17th to the early 20th century—but the book isn’t by Aristotle, and it’s not usually considered a masterpiece. First printed in London in 1684, it was imported to the American colonies and then became a staple of early publishing in the United States, going into hundreds of editions.

An anonymous writer compiled the book from several earlier texts. He or she borrowed the name “Aristotle” to make the work seem scientific when the book was first published. It was still for sale in London’s Soho sex shops right up into the 1930s. Primarily a late 17th-century manual on pregnancy and childbirth—an early-modern precursor to today’s perennial bestseller What To Expect When You’re Expecting—the book endorses sexual pleasure but also includes images of deformed infants, or so-called “monster babies.” This seemingly bizarre combination of contents contributed to the book’s long-lasting appeal.

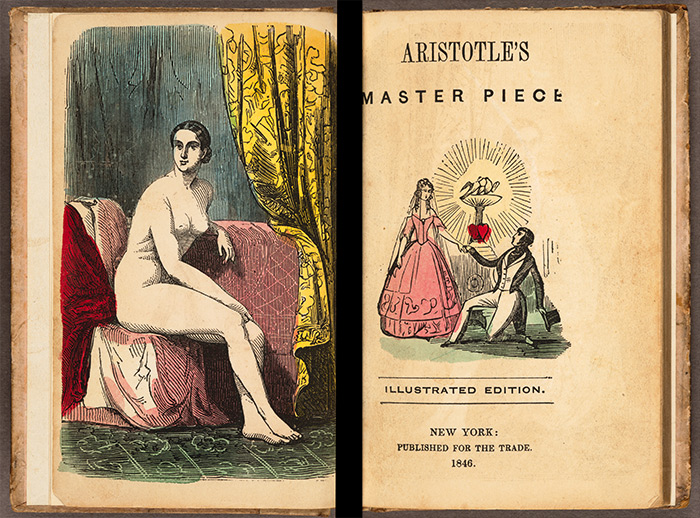

By the 19th century, the Masterpiece often combined a racy appeal to male readers, as in the image on the left, with a family-oriented appeal, as in the romantic depiction on the right. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Mary Fissell, professor of the history of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, is currently writing a cultural history of Aristotle’s Masterpiece, focusing on its production and reception in Britain and the United States. On April 22 in Rothenberg Hall, Fissell presents the George Dock Lecture in a public talk titled “A Look at America’s First Sex Manual.” (You can listen to the lecture on iTunes U.)

Fissell finds Aristotle’s Masterpiece intriguing because its ubiquity has made it possible for her to discover stories about readers encountering the text in the past. “I know about adolescent boys stealing their mothers’ copies, a teenage girl reading it aloud in a factory lunchroom, and working-class couples who kept it hidden in their bedroom,” she says. Such stories provide rare glimpses into the otherwise hidden world of plebeian sexuality.

“The book’s persistence suggests that there’s something about its vision of sex and making babies that remains profoundly appealing across the centuries,” Fissell says. “Part of my task has been to figure out exactly what that something is.”

These are the only known surviving examples of the woodblocks used to illustrate Aristotle’s Masterpiece. The images were carved and recarved over centuries, indicating that publishers thought them essential to the book’s appeal. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Her research on the subject led her to The Huntington’s collections, where she came across items in unexpected places. She was surprised and delighted to see a set of woodblocks used to produce editions of the Masterpiece. “After having spent years thinking about how this book was produced, it was really moving to actually hold a woodblock used in the north of England in the early 19th century,” Fissell says. “These kinds of cheap books aren’t often the focus of scholarly study, but I’m impressed by the skill of the artists.”

Another unexpected find at The Huntington lay in the correspondence of the 19th-century radical Richard Carlile, who printed the first birth-control pamphlet in Britain, which in turn prompted a Boston doctor, Charles Knowlton, to do the same in the United States. One of Carlile’s associates, William Holmes, described the Masterpiece in court, claiming that it wasn’t really a dirty book—even if it did have a picture of a naked woman as its frontispiece. One gains insight into just how radical the very idea of contraception was to Carlile and Holmes; their letters grant readers rare access to working-class ideas about sex and reproduction.

At times, the Masterpiece is a bit like a fly in amber, preserving Renaissance ideas into the 19th and 20th centuries. This winged figure, the text tells us, was born in Ravenna, Italy, in 1513. Such monstrous images offered readers a thrill of horror and became something of a trademark for the work. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Mary Fissell’s April 22 lecture, “A Look at America’s First Sex Manual,” will take place at 7:30 p.m. in Rothenberg Hall. The event is free and open to the public; no reservations required.

Kevin Durkin is the editor of Verso and managing editor for the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.