Posted on Tue., July 26, 2016 by

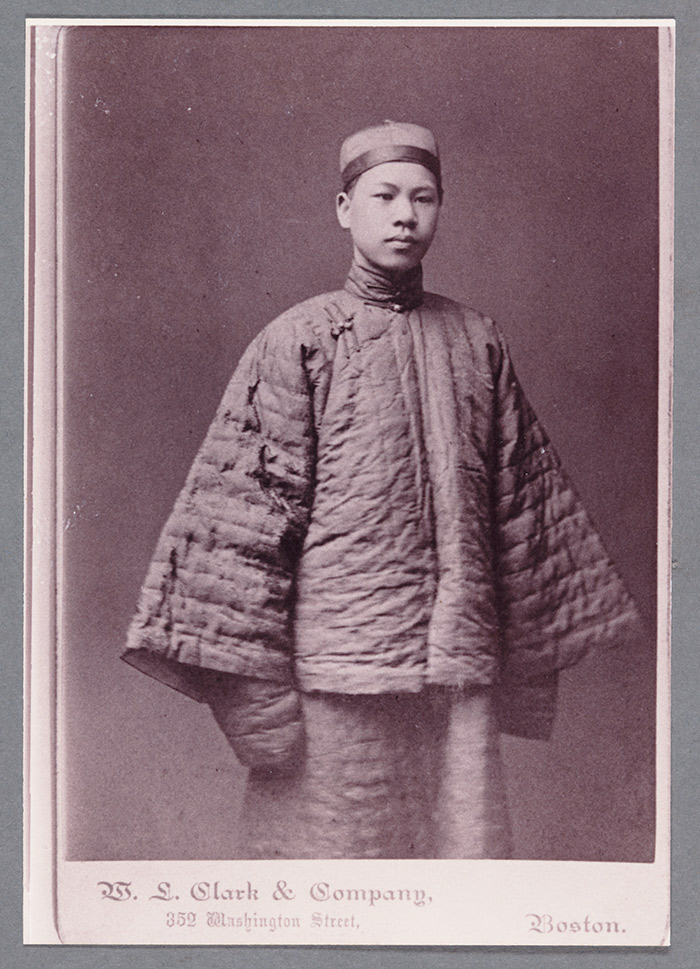

Hong Yen Chang as a Chinese Educational Mission student to the United States in the 1870s. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1890, a Chinese-born national named Hong Yen Chang arrived in California from New York, where he had obtained a degree from Columbia Law School and a license to practice law. He filed a motion to practice in California, presenting his New York State license and his certificate of naturalization. Those documents should have met the conditions for admission to the California bar. And yet his motion was denied.

What was the rub? Under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, citizenship was not available to the Chinese. The Court ruled that his certificate of naturalization was invalid.

Hong Yen Chang, ca. 1890, around the time he moved from New York to California, hoping to practice law. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington has acquired correspondence, photos, certificates, and licenses belonging to Chang, who is considered the first Chinese lawyer in the United States. Chang was denied a law license but went on to enjoy an illustrious career in banking and diplomacy, holding positions as accountant general to the Shanghai Bank treasury and as Chinese consul in Vancouver, Canada.

“The Chang papers are an important addition to our collection of materials on Chinese American history,” says Li Wei Yang, The Huntington’s curator of Pacific Rim collections. “Hong Yen Chang was a significant figure during the infamous Chinese Exclusion era, along with other important leaders of the Chinese American community, including Y.C. Hong, Jack Wong Sing, and Jack Chow—all of whose papers reside at The Huntington.”

Charlotte Ah Tye Chang (Hong Yen Chang’s wife), year unknown. She was one of the first Chinese social workers in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Chang appealed the decision denying him a law license to practice in California—fighting all the way up to the California Supreme Court. But the court wouldn’t budge. Finally, in 2015, a group of law students from the UC Davis School of Law’s Asian Pacific American Law Students Association took up Chang’s cause.

On March 16, 2015, the California Supreme Court decided unanimously to give a posthumous law license to Chang, resolving that it was “past time to acknowledge that the discriminatory exclusion of Chang from the State Bar of California was a grievous wrong.”

Hong Yen Chang, second row, far left, dressed in Western-style clothing and a bowler hat, at the time when he served as the accountant general to the Shanghai Bank treasury. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Chang first came to the United States in the 1870s as a student in the Chinese Educational Mission, a program designed to teach Chinese youth about the West. He enrolled at Yale College in 1879, but in 1881, the Chinese government recalled all mission students, and Chang returned to China. Unlike most other mission students, Chang was able to return to the United States, and with the financial support of his brother, he completed his education.

Chang graduated from Columbia Law School in 1886 but initially was not allowed to practice law because he lacked U.S. citizenship. Later, a judge in New York helped Chang argue his case in front of New York Governor David Hill. In 1888, Chang was granted both U.S. citizenship and the right to practice law in New York. Then he traveled to San Francisco, hoping to serve the large Chinese community there.

Hong Yen Chang, first row, far right, dressed in Western-style clothing. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Chang’s collection includes letters and documents concerning his days as a diplomat and consul for the Republic of China. Also in the collection is a letter by Soong Ching-ling, the second wife of Sun Yat-sen, a leader of the 1911 revolution that established the Republic of China; she later went on to become vice president of China, under Mao Zedong, from 1949 to 1954. There is also a smaller portion of papers in the collection about Yee Ah Tye, Hong Yen Chang’s father-in-law, who was a prominent Chinese merchant in San Francisco.

The Huntington’s Yang expresses gratitude to Yee Ah Tye’s great-granddaughters—Rachelle Chong, Lani Ah Tye Farkas, and Doreen Ah Tye—for donating these important papers. “Once the Chang papers are processed,” says Yang, “they will provide researchers with insights into Chang’s life and his contributions to the Chinese community in the United States.”

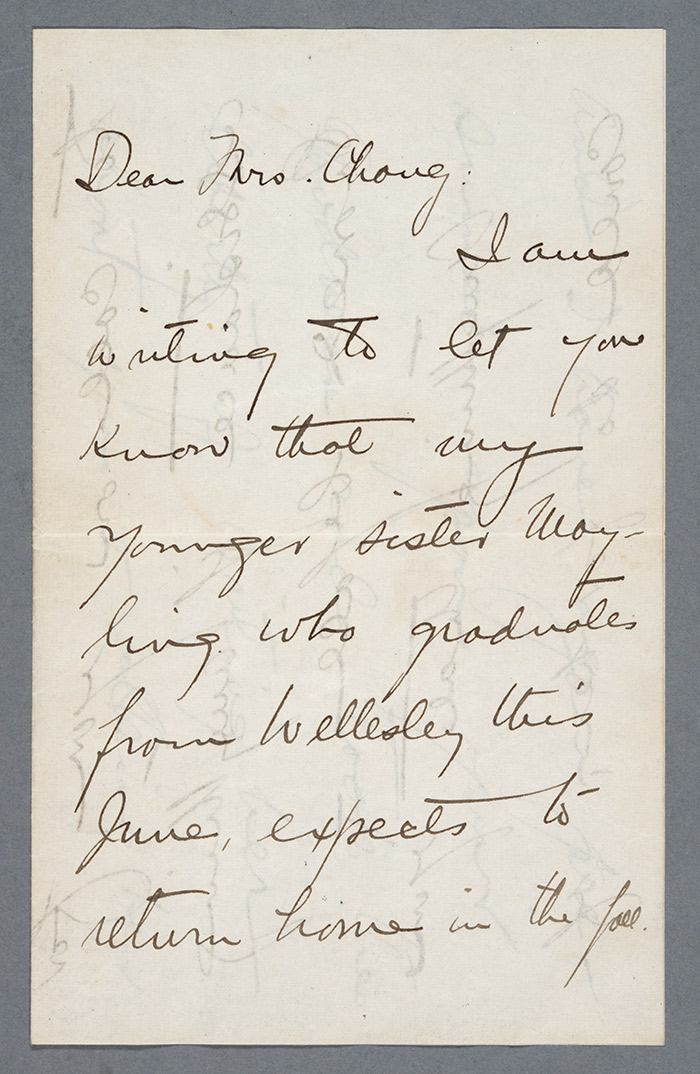

Letter from Soong Ching-ling to Charlotte Ah Tye Chang (Hong Yen Chang’s wife), March 14, 1917. Soong Ching-ling, who was educated in the United States, was the second wife of Sun Yat-sen, a leader of the 1911 revolution that established the Republic of China; she later went on to become vice president of China, under Mao Zedong, from 1949 to 1954. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Related content on Verso:

Chinese-American Advocate, Y.C. Hong (Dec. 15, 2015)

Kevin Durkin is editor of Verso and managing editor in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.