The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Stories Aboard the Aquitania

Posted on Fri., Sept. 4, 2015 by and

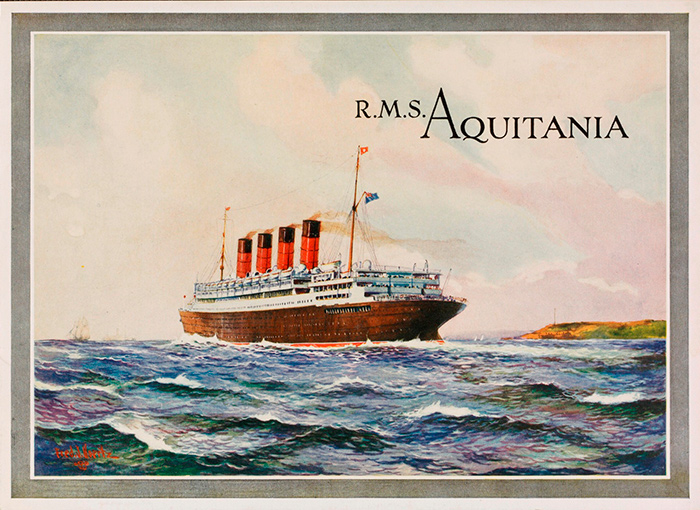

Cover of a brochure for the RMS Aquitania, from Cunard Steamship Company, ca. 1925. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

After they married in 1913, Henry and Arabella Huntington would spend several months each year in Europe, staying at the Château de Beauregard, a lavish castle located north of Paris, near Versailles. Reaching the Continent in those days meant traveling by ocean liner, and for the well-heeled Huntingtons, there was no better option than Cunard’s RMS Aquitania, considered one of the world’s great luxury vessels.

We know a great deal about the Aquitania, thanks to The Huntington’s John H. Kemble Maritime Ephemera collection, which includes 24,000 brochures, flyers, and assorted items, more than 1,500 of them relating to Cunard’s line of ships.

There’s also an oft-recounted story about the Huntingtons aboard the Aquitania. As the story goes, in 1921, they booked one of Aquitania’s two regal suites. Also on board was noted art dealer Joseph Duveen. The art dealer joined the couple in their private suite of rooms—the Gainsborough Suite, according to the tale—where Henry noticed a reproduction of Thomas Gainsborough’s famous painting Blue Boy and asked Duveen if the real thing was for sale. (This account appeared in S.N. Behrman’s 1951 work, Duveen, based on a series of articles in The New Yorker magazine.)

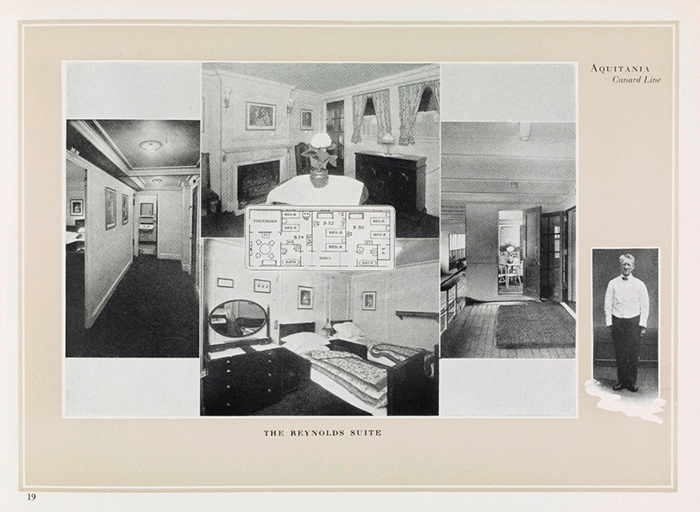

Photographs and a plan of the Reynolds Suite, a mirror image of the Gainsborough Suite, from the RMS Aquitania brochure, ca. 1925. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Most good stories contain some delectable facts along with certain embellishments, and that’s probably the case with this one. Of course, Henry and Arabella knew of Blue Boy well before they boarded the Aquitania. The painting was already famous, and Henry owned a print of it as early as 1901. Duveen had certainly coveted the painting long before that transatlantic crossing, with one newspaper article referring to Duveen’s 20-year quest. What we can confirm is that the Huntingtons traveled to France in 1921 and shortly thereafter purchased the painting. (These two facts are documented in Shelley M. Bennett’s The Art of Wealth: The Huntingtons in the Gilded Age.)

The Kemble Maritime Ephemera collection also fills in many of the blanks about the Aquitania. According to a lavishly illustrated brochure about the ship, its Gainsborough Suite had three bedrooms, two bathrooms, and a veranda. It boasted “accommodation for a family and servants to cross the ocean in magnificent seclusion,” appointed with “gracious mahogany and brocade of the 18th century.” The Huntingtons would have had the choice of taking meals in their private dining room—presumably with the reproduction of Blue Boy gazing from above—or joining other first-class passengers in the sumptuous Louis XVI Restaurant.

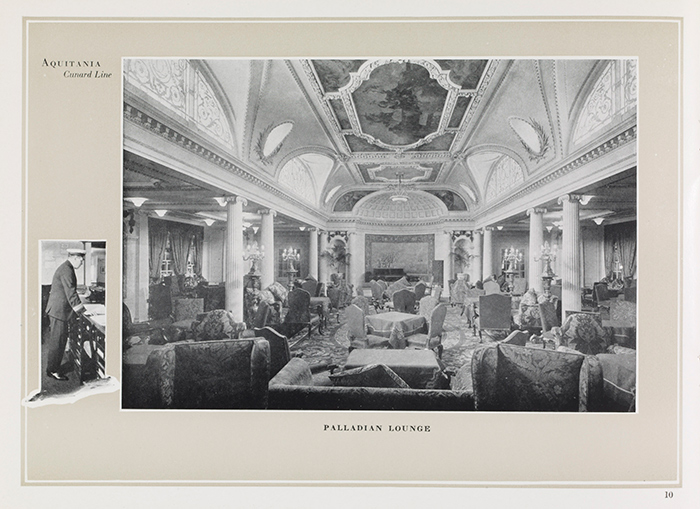

A view of the Palladian Lounge, an elegant room recalling the designs of 16th-century Venetian architect Andrea Palladio, from the RMS Aquitania brochure, ca. 1925. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

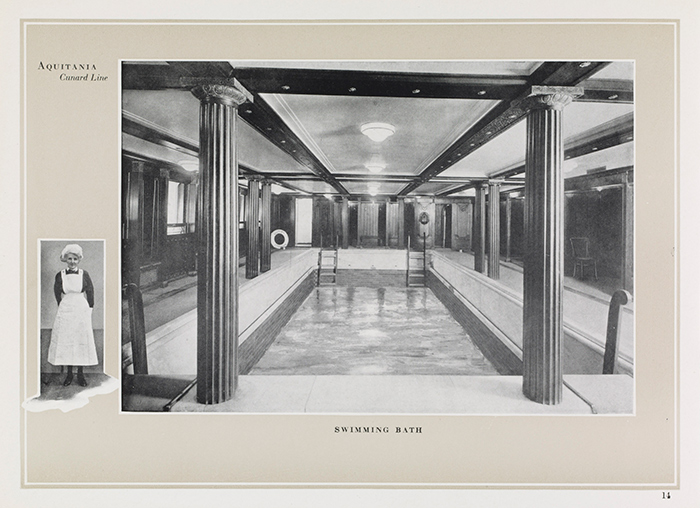

We also know the ship featured first-class public rooms, including the Palladian Lounge, “a room of majestic size and proportions,” which served as the “meeting-place of the society of the ship,” and the Smoking Room, with its T-shaped Admiral’s Walk. For entertainment, there was also a first-class swimming bath. Keeping everything (and everyone) in tip-top shape were hundreds of stewards, a gardener, several doctors, and even a manicurist.

Despite the luxurious accommodations, the 1921 crossing would prove to be the Huntingtons’ last. As noted by Bennett, Henry had written to Duveen the previous year, asking for his help in being released from the 10-year lease he held on the French castle. “As you well know,” Henry wrote, “Mrs. Huntington is very fond of the Chateau, and there is certainly no more beautiful place in France, and I quite agree with her, but with my large and varied interests in America, I feel that I should remain there a large proportion of the time.”

For entertainment, first-class passengers had at their disposal a pool, a gymnasium, and a series of lounges, from the RMS Aquitania brochure, ca. 1925. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

For her part, Arabella knew of Henry’s reluctance to return to France but hoped she could convince him otherwise. “He thinks he will never come back here,” she wrote to her son Archer just a month later, “but he is mistaken. I am devoted to this place never liked any place so well & I won’t give it up if I can help it & I think I can.”

In the end, Henry prevailed, as he often did. Through Duveen, he acquired Blue Boy from its British owner, the Duke of Westminster, who had fallen on hard times. He also found a way to break his lease to the castle in France, putting a stop to the couple’s yearly jaunts to the Continent.

As for the Aquitania, it served a variety of purposes during its 36 years of service, not only ferrying many wealthy passengers across the Atlantic, but also helping to transport troops during both world wars. It met its demise in 1950, being scrapped in a shipyard in Scotland.

We owe a debt of gratitude to the John H. Kemble Maritime Ephemera collection. The Aquitania may be gone, but items from the collection allow us to relive stories from a bygone era—some true, and some perhaps only imagined.

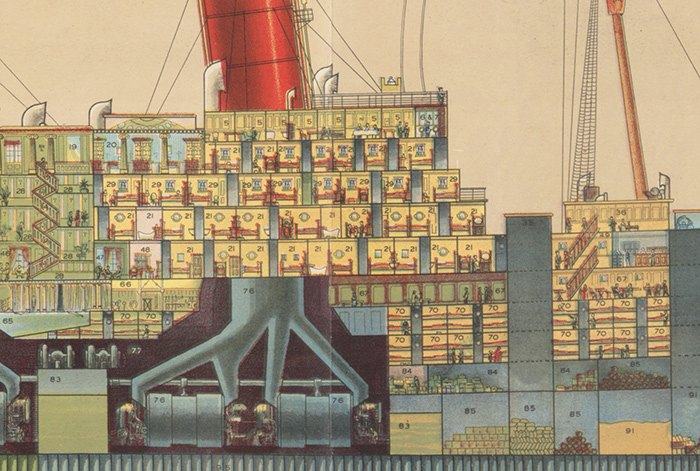

Detail of a cutaway depiction of the RMS Aquitania, starboard side, foldout brochure, ca. 1921. The index accompanying the cross-section indicates that rooms labeled with the number 29 are the “Reynolds and Gainsborough Suites and 1st Class Accommodation.” Full image available here. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Related content on Verso:

Buying a Turner (Feb. 20, 2015)

How Do You Frame a Masterpiece? (Oct. 24, 2013)

A Wealth of Information (July 16, 2013)

Mario Einaudi is the Kemble Digital Projects Librarian at The Huntington.

Diana W. Thompson is senior writer for the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.