The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Spirit of Party

Posted on Tue., Oct. 30, 2018 by

Washington's farewell address to the people of the United States, Philadelphia: Devereux & Co., ca. 1858. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Few documents of the Founding era were more admired in the United States before the Civil War than George Washington's Farewell Address. Americans liked to think of themselves as the same nation to which its first president appealed in 1796—patriotic citizenry with "reflecting and virtuous minds" whose "love of liberty" was interwoven "with every ligament" of their hearts and who held dear the "unity of government" that made them "one people."

However, the American public could not help but see the chasm between this ideal and reality. Nowhere was this contrast starker than in the United States Congress. Rife with all possible vices—from hard drinking to physical violence—Congress had long provided fodder for ridicule and outrage.

When 16-year old Irving S. Vassall moved to the nation's capital from his native Oxford, Massachusetts, he found the political scene in Washington, D. C. disappointing. Congressmen looked nothing like wise statesmen, and the town was awash in rumors and gossip about congressional shenanigans, which Vassall gleefully reported to his Massachusetts relatives.

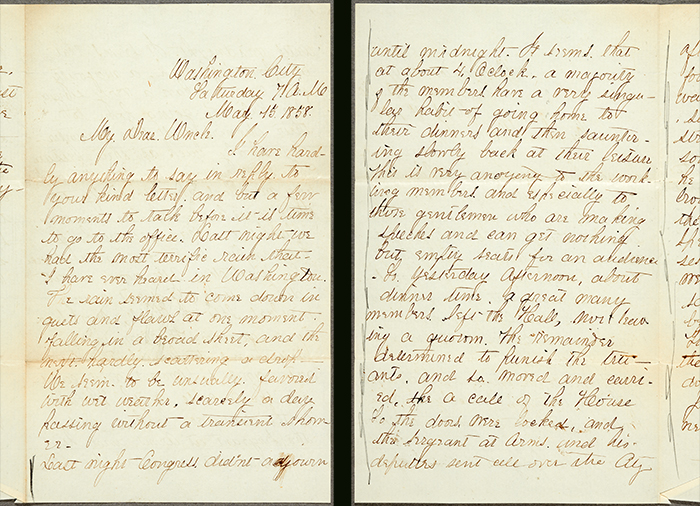

On May 15, 1858, Vassall related one such rumor to his uncle. It seemed that a majority of congressmen had developed "a very singular habit of going home to their dinners and then sauntering slowly back at their leisure," much to the annoyance of the "working members" of Congress. On the afternoon of May 14, having found "a great many members" missing in action, they sent the sergeant-at-arms and his deputies into "the city after his stray sheep." The congressmen were yanked from dinner parties (including one hosted by President James Buchanan at the White House) or pried from the arms of many "a pretty lady" and delivered to the House, where they were fined "two dollars each."

The incident was duly recorded by the Congressional Globe, although less colorfully than in Vassall's letter. Quite a few members from both sides of the aisle had indeed made themselves scarce before the speaker called the session adjourned, rendering the rest of the House unable to proceed without a quorum. As the sergeant-at-arms brought in fugitive congressmen, the excuses piled up, prompting an occasional outburst of hilarity. A large portion of the Pennsylvania delegation called in sick, save William Stewart, who, according to his fellow Pennsylvanian Republican John Covode, was "in perfect good health, and in order to preserve his health, I presume he had gone to dinner."

The first two pages of a letter by the 16-year-old Irving S. Vassall to his uncle regarding congressional absenteeism, May 15, 1858. Vasall writes that a majority of congressmen developed "a very singular habit of going home to their dinners and then sauntering slowly back at their leisure." Clara Barton correspondence. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Congressional Globe reported the incident as a bipartisan affair. Vassall, however, described the roundup of the malingerers as "chiefly the work of the Republicans and done no doubt to break up Jimmy Buchanan's dinner party."

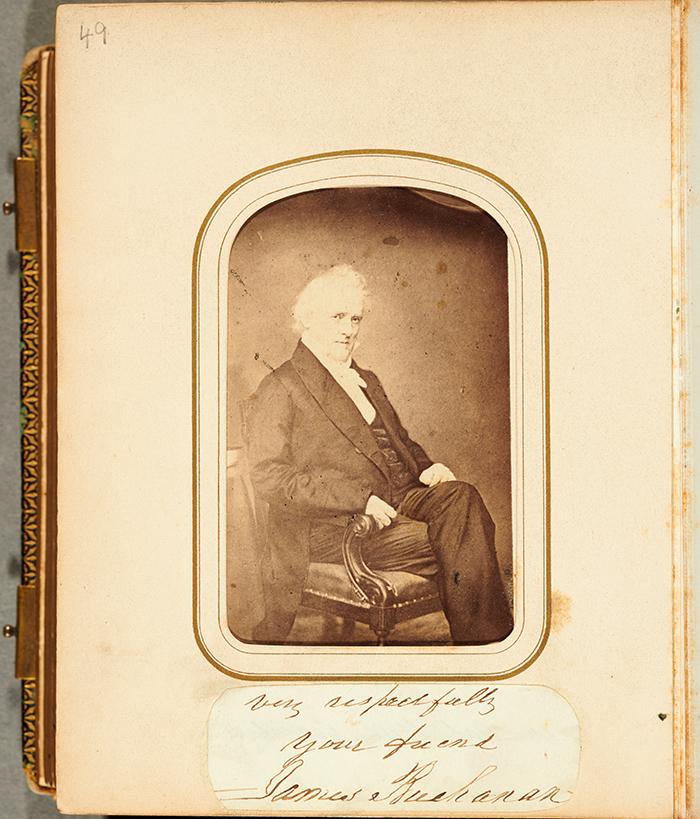

It was little wonder that Washington gossips would see it this way. There was no love lost between President Buchanan, a pro-slavery Democrat, and the members of the new Republican Party, which had included opposition to slavery in its official platform.

The May 14 incident came just four months after the scandal over the admission of Kansas to the Union—an event in which congressional absenteeism played an important part.

In his annual message to Congress in December 1857, Buchanan endorsed the Lecompton Constitution, which defined Kansas as a slave state. Determined to ram the proposal through Congress, the President sent it for ratification on February 2, 1858. For three days, the debates between the pro-and anti-Lecompton factions raged in the House, producing an impasse.

At the end of the business day on February 5, the Republicans discovered that a large chunk of the pro-Buchanan Democrats had decamped for dinner and, seizing on their temporary majority, tried to force the vote. Alexander H. Stephens, who was then Buchanan's floor manager, stalled while messengers labored to round up pro-Buchanan congressmen all over Washington and herd them back to the House.

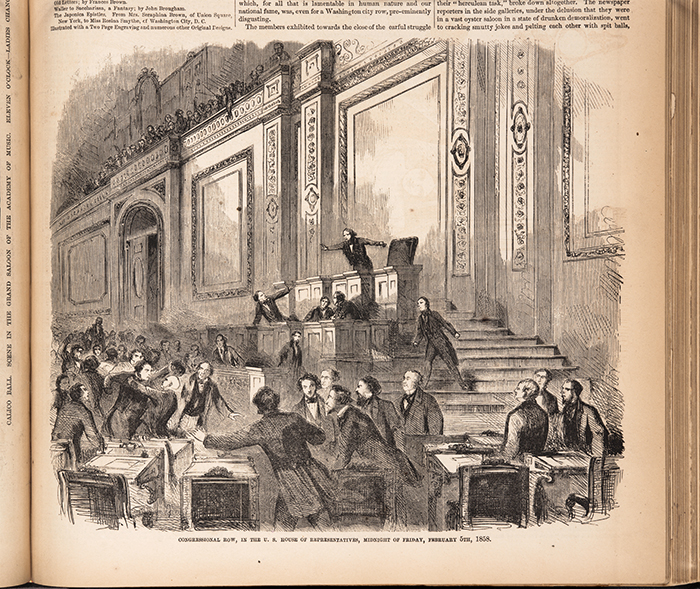

The proceedings dragged on into the night, as the House, according to a Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper reporter, descended into a scene of "mental and physical fermentation." The "Western delegates" napped, hanging "over the backs of their chairs, displaying open mouths and giving utterance to dreadful sounds." Others sustained themselves with "private drinks," innumerable "plugs of tobacco," and "vile cigars." In the side-galleries, newspaper reporters were engaged in "pelting each other with spit balls, the solid contents of which were the President's Kansas message."

James Buchanan, ca. 1844–1856. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Just before 2 a.m., Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania, the Republican whip, crossed the aisle to confer with some anti-Lecompton Democrats. Laurence Keitt a pro-slavery Democrat from South Carolina, took exception and advanced on Grow, calling him a "black Republican puppy." Grow refused to yield to a slave driver who would "come up from his plantation and crack his whip about my ears," at which point Keitt grabbed him by the throat.

In an instant, some "forty or fifty Republicans" came dashing across the floor, including Cadwallader C. Washburn of Wisconsin who "pitched into the ring, causing an immense rolling over on the floor of numerous specimens of the collected wisdom of the nation."

As United States representatives bashed at each other with their fists and, in the case of John Covode of Pennsylvania, a heavy stoneware spittoon, the Speaker of the House pounded away with his gavel, battering his desk "into mincemeat." The sergeant-at-arms seized the Mace of the Republic, topped with a silver eagle, but could do little more than wave this "emblem of the valorous critter" over the heads of the warring parties.

The fight reached its climax when John Fox Potter of Wisconsin, a Republican, seized William Barksdale of Mississippi, a Democrat, by what he thought was "the hair of the head." To his horror, the hair came off in his hand. It turned out that the Barksdale wore a wig—a fact that he had carefully concealed from his colleagues. The hall convulsed in laughter, which brought an end to what the Frank Leslie's reporter characterized as a "pre-eminently disgusting" scene.

Such scandals were vivid examples of what Washington had called in his Farewell Address "the spirit of party." Washington had warned that "party passions," rooted in the basest instincts of human nature, would cause "riot and insurrection," and he implored his countrymen to exercise "a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame."

Sixty years later, the warning looked like a prophesy fulfilled. The "spirit of party" was now rampant.

Some Americans thought that this spike in partisanship was merely due to a lack of patriotic restraint and an unwillingness to compromise. This danger could be contained, they thought, by cultivating the civic virtues of putting country above party and by the mitigating "force of public opinion."

"Congressional Row, in the U. S. House of Representatives, Midnight of Friday, February 5th, 1858." Leslie's Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, Volume 5, Number 16 (Feb. 20, 1858), page 176. In the lower left part of the image, the illustrator has captured the moment when John Fox Potter of Wisconsin, a Republican, seized William Barksdale by what he thought was "the hair of the head," only to find himself holding aloft the Mississippi Democrat's wig. Leslie's Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, Volume 5, Number 16 (Feb. 20, 1858), page 176. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Many others, however, saw this new partisanship as part of a battle for the very soul of the Republic. There was little room for compromise. Abolitionists were determined to rid the nation dedicated to liberty of the sin of human bondage. Antislavery politicians fought to check the power afforded to the Southern "slaveocracy" at the expense of free states. The pro-slavery establishment, insisting that slavery was a God-ordained "positive good" and the foundation of the nation's prosperity, demanded that it be federally protected.

The struggle, which had fractured the political establishment, could no longer be contained by the lofty conventions of parliamentary civility and stately procedure nor checked by increasingly divided public opinion. While some citizens saw the Republic in chains, groaning under the yoke of "Slave Power," others beheld the Founders' legacy of (to use the words of a prominent Southern preacher) "regulated freedom" assailed by wild-eyed, extremist "black Republicans," as well as by "atheists, socialists, and communists."

Americans liked to invoke Washington's warning against "the spirit of party," but only as long as it applied to the opposing camp. While professed to be disgusted by resurgent partisanship, a portion of the public, including the young Irving Vassall, could not help but relish the spectacle, especially as it played out in Congress.

In three years, Vassall—sick with consumption and unable to enlist in the Union army—joined the staff of Colonel Gardiner Tufts, the military agent for the state of Massachusetts and inspector of hospitals and prisons. As Tufts' chief clerk, Vassall inspired his aunt, Clara Barton (1821–1912), the pioneering nurse who later founded the American Red Cross, to take up the cause of missing soldiers and prisoners of war. Vassall died at the age of 24, on April 9, 1865—on the very day that Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant.

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American History at The Huntington.