The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Curious Afterlives of Ambroise Paré

Posted on Wed., Nov. 14, 2018 by

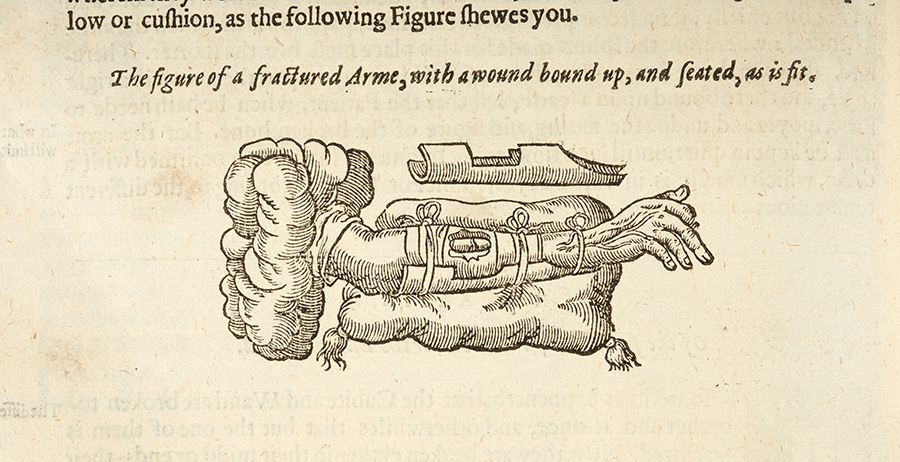

Bone fractures were a difficult and important surgical problem, one Paré treated in his writings. This detail from the 1634 English edition of Paré’s collected writings illustrates a passage on fractures in the bones of the forearm accompanied with wounds. He writes that they should be set and held steady, supported with “plates of Latin, or Past-bord” and rested “upon a soft pillow or cushion,” in the manner depicted. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The French surgeon Ambroise Paré occupies a curious place in medical history. He is a towering figure in Renaissance medicine and the history of surgery, and yet relatively unknown, especially next to prominent contemporaries like the anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) or the nonconformist thinker Paracelsus (d. 1541). While well known to historians of medicine and historically minded medical practitioners—many of their subfields trace their lineages to or through Paré—his star is dimmer elsewhere, even among other historians of early modern Europe (1500–1800).

I have been reflecting on Paré’s curious afterlives while working on the impressive collection of his texts held at The Huntington. As a Molina Fellow in the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences at The Huntington this year, I am researching the history of forensic medicine in the west. This means that I must explore Paré, as he was a key figure in early legal medicine. He touched on a dizzying range of topics in print, producing an oeuvre that helps us understand what could fit within messy categories like “surgery” and “medicine” in this period.

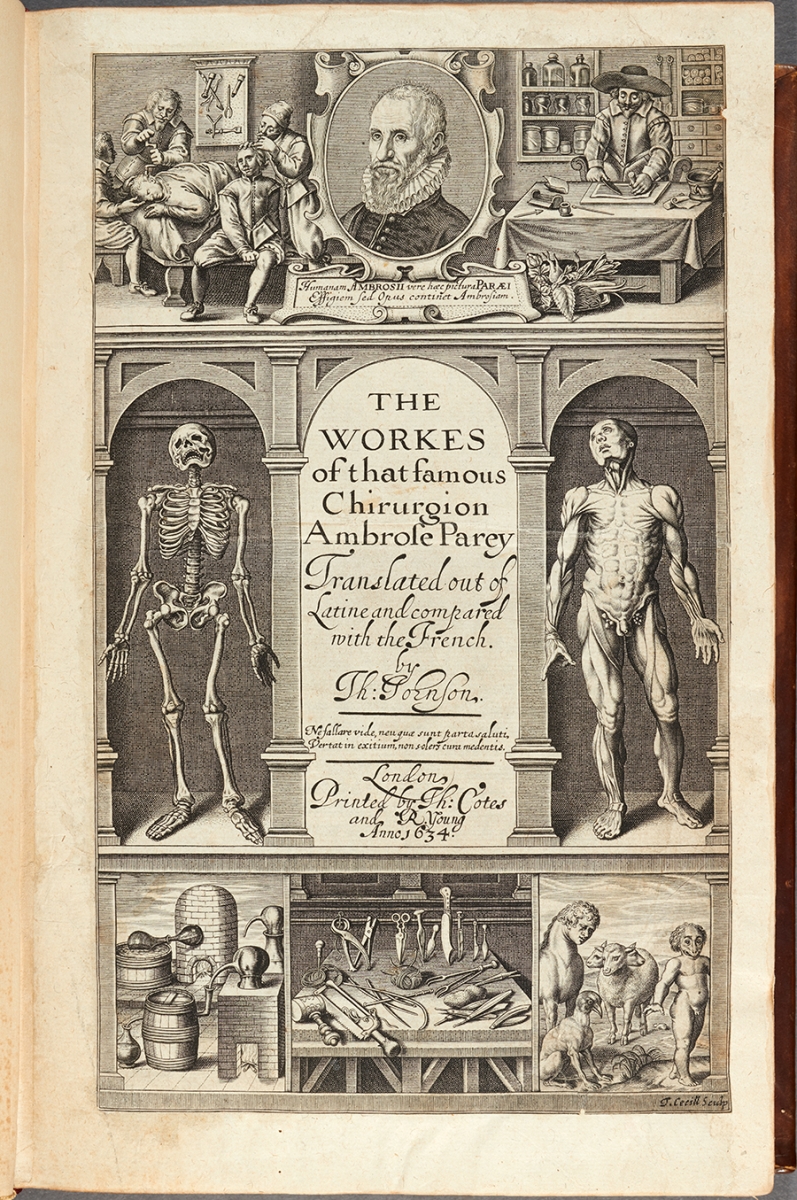

The title page to the 1634 English edition of Paré’s collected writings, translated by Thomas Johnson, hints at how widely his interests ranged. It shows not only surgical tools and famous surgical procedures like trepanation, but also indicates that he will tell readers about human anatomy, “monsters” and teratology (the study of developmental “abnormalities” in living organisms), the preparation of medicines, and more. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Born in provincial northwestern France around 1510, Paré sought his fortune in barber-surgery, the closest thing there was to a medical jack-of-all-trades. Quite unlike in our own time, surgery in Paré’s Europe was a low-status occupation. Practitioners were often organized into municipal trade guilds together with barbers—men who cared for beards, teeth, nails, and other aspects of physical appearance. There was good sense to such alliances, as routine surgical work was closely connected to the barber’s craft. Surgeons cared for the exterior of the body as well, healing wounds, cutting warts, lancing boils, and treating skin problems. They were legally restricted to such work; formal regulations gave physicians reign over the interior of the body and apothecaries the sole power to concoct and dispense drugs.

Surgeons sometimes dealt with afflictions requiring more serious interventions as well—from bladder stones to cataracts, and from compound fractures to conditions requiring amputation. Invasive measures were exceptionally dangerous, and not all surgeons would consent to undertake them. Paré developed great expertise in them, however, training first in the provinces and then in Paris, where he served at the storied Hôtel-Dieu, the most prominent hospital in the nation.

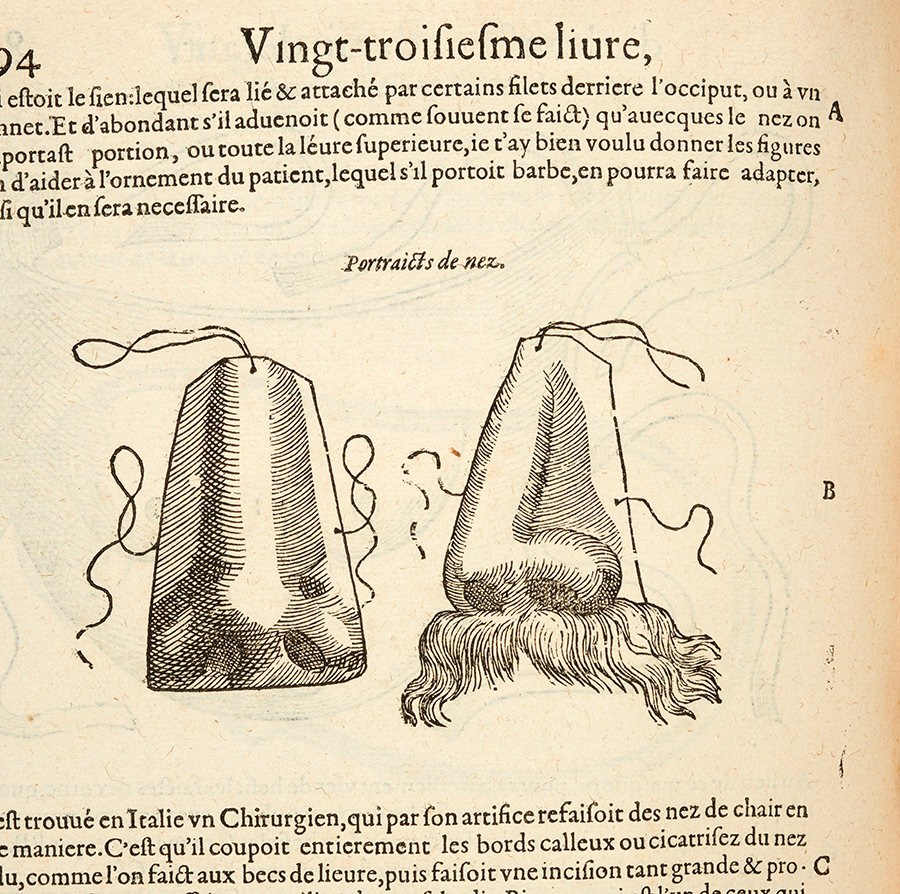

Two views of a prosthetic nose from the 1614 French edition of Paré’s complete works. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Paré learned by observing and doing. Surgery was not a lettered occupation, and the intensive book-based education of contemporary universities was reserved for physicians, the medical elite. While Paré’s written works would eventually win him great renown, he never became well versed in Greek and Latin, and his writing style is rough and unpolished.

This style suited Paré’s subjects and audiences. He often wrote for the benefit of other workaday surgical practitioners, covering an enormous range of medical topics. Indeed, he attracted harsh criticism for going far beyond the traditional remit of surgery and for revealing surgeons’ secrets. The title page of the 1634 English edition of Paré’s collected writings gives some sense of that range, suggesting that the text will touch on everything from surgical tools to teratology (the study of developmental “abnormalities” in living organisms).

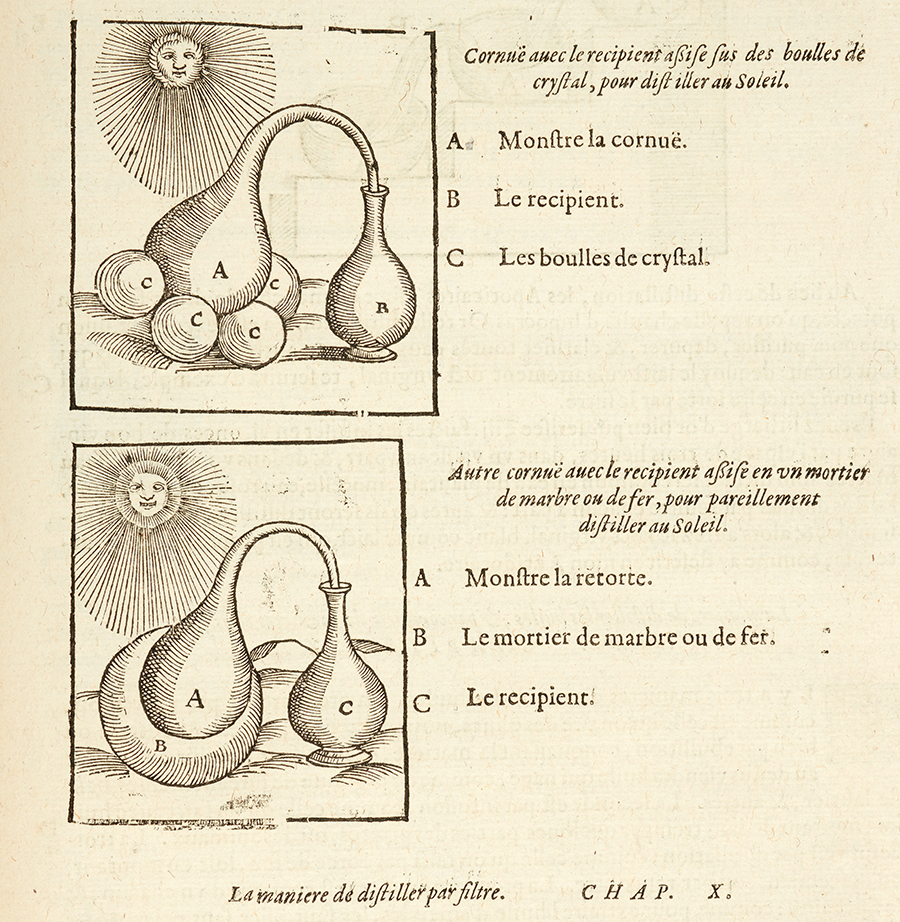

Detail of a page on distillation in the 1614 French edition of Paré’s complete works. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Paré divided his career between peacetime practice in France’s capital and wartime service as a battlefield surgeon, the subject of some of his most vivid writing. He became a master barber-surgeon in the 1540s, began a family, excelled in his profession, and eventually graduated to master surgeon, joining the formal body organizing Paris’s learned surgical elite, the Confraternity of Saint-Côme (named after St. Cosmas, one of the patron saints of surgery).

A shrewd social climber and businessman, Paré’s practice brought him to the upper reaches of what was possible for a surgeon at the time. He served four French kings, as well as Catherine de Medici. This standing gave Paré freedom to publish widely, with his collected works (Oeuvres Completes, published in 1575, 1578, and, in Latin, in 1582) attempting a sort of comprehensive coverage of the field that did indeed infringe on the realms of doctors, apothecaries, and many others. His work consciously stretched the definitions of surgery and advocated for greater respect for his surgical brethren.

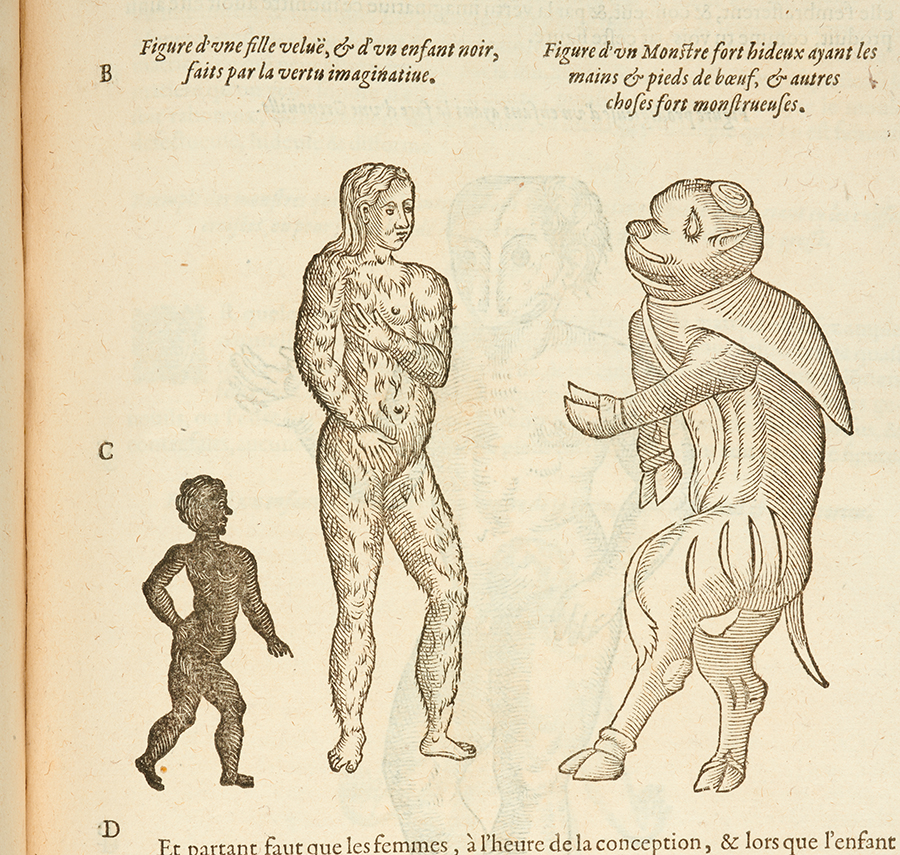

Left, a “hairy girl” and “black child.” Right, “a very hideous monster” with “hands and feet of an ox” as well as “other very monstrous things.” Paré uses these examples to illustrate the power of the maternal imagination, which many felt could shape the unborn fetus. For instance, he tells his readers that the girl was “bred so deformed and hideous” because her mother focused on a picture of St. John the Baptist, himself hairy, clothed in animal furs, at the moment of conception. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Much of what he discussed was quite obviously appropriate to surgeons. Wound care, instrument design (including his own), and battlefield medicine were all traditionally surgical topics. Paré made influential arguments against treating gunshot wounds with boiling oil and in favor of stopping an amputee’s bleeding with arterial ligation (tying arteries shut with thread) instead of cauterization (closing them off by burning). He also contributed to developments in early modern prosthetics, including describing and depicting prosthetic noses.

Elsewhere he went farther afield, writing about such topics as distillation; embalming dead bodies; forensic pathology and forensic reports on it; the use of “mummy” and “unicorn horn” as medicines; medical simples (single-ingredient medicines); poisons; and human reproduction. One of his enduring modern claims to fame has to do with obstetrics; he argued for the reintroduction of podalic version, a procedure for turning an abnormally positioned fetus to allow feet-first delivery. His work on the plague, which he claimed to have survived, contains some of his most striking, passionate prose. In treating such topics, he showed his own wide-ranging interests and argued forcefully that surgical practitioners should not be restricted to traditional, narrow occupational definitions.

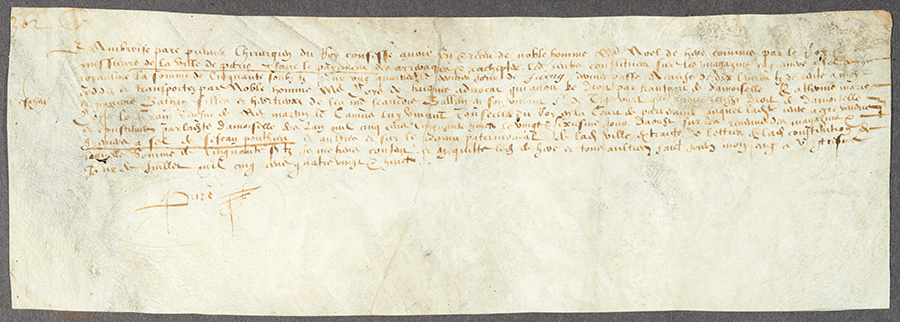

This document is a receipt or agreement of payment from a “Maître François de Vigny” to Ambroise Paré, July 15, 1573. On loan from the Los Angeles County Medical Association since 1992. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Paré’s writings on “monsters,” marvels, prodigies and the like have been of enduring interest to later readers. Beings—human, animal, and perhaps otherwise—who displayed apparently preternatural or supernatural differences fascinated early modern people, who sought to explain such differences or interpret divine messages in them. His treatment of this subject makes for truly challenging reading in a time when we are often—though by no means always—accustomed to respectful treatment of bodily difference.

It is a challenge worth facing, though. The Paré texts that The Huntington holds, both early modern and modern, in French and English, are strange, rich things. The images alone warrant study, as does a unique manuscript document signed by the surgeon himself. On its own, this small text—a receipt or agreement of payment from a “Maître François de Vigny” to Paré—may shed little light on Paré and his work, but it’s a thrill to see such a mundane document that passed through the great surgeon’s hands.

Seth LeJacq is a lecturing fellow in Duke University’s Thompson Writing Program and a 2018–19 Molina Fellow in the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences at The Huntington.